-

2025-12-15 21:47

2025-12-15 21:47

By Mona Hojat Ansari

‘A very positive path’: Iran and Belarus strengthen alliance against sanctions

Araghchi holds meetings with top Belarusian officials on first Minsk visit as FM

TEHRAN – On Monday, Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi landed in Minsk before heading to Russia, where his day of meetings with top Belarusian officials focused on how Iran and Belarus can support each other in counteracting escalating Western sanctions and pressure.

-

By Shahrokh Saei

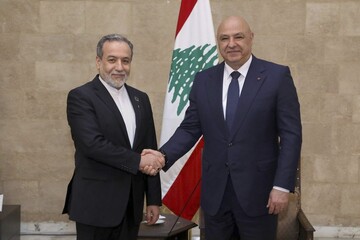

Israel’s media war fails to divide Iran and Lebanon

TEHRAN – Israeli media and their affiliates recently tried to stir the pot, spotlighting a brief back-and-forth between Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi and his Lebanese counterpart Youssef Raggi, in an effort to paint the two countries as being at odds.

-

By Sondoss Al Asaad

Lebanon at the edge: Diplomacy between fire and restraint

BEIRUT—Lebanon has entered a critical moment. An intense flurry of regional and international contacts is unfolding against the backdrop of open Israeli threats against Lebanon and mounting internal pressure.

-

By Wesam Bahrani

38 years after the founding of Hamas

TEHRAN – Hamas affirms that Operation al-Aqsa Flood marked a pivotal moment in the Palestinian people’s struggle against occupation.

-

Leader’s aide reiterates Iran’s backing for Hezbollah amid US push to disarm Lebanese Resistance

TEHRAN – Ali Akbar Velayati, an advisor to Iran’s Leader and the country's former foreign minister, stated to Hezbollah’s representative in Tehran that Iranians will continue to lend their full support to the group in the face of Israeli aggression on Lebanon and an American push for the Lebanese government to disarm the Resistance movement.

-

Expo of creative, knowledge-based firms to focus on AI

TEHRAN – The fourth exhibition showcasing the achievements of creative and knowledge-based companies is scheduled to take place from December 28 to 31 in Tehran, with a focus on artificial intelligence (AI).

Politics

-

Grossi heroized by Western media: Bias and IAEA limits ignored

Recent Western media portrayals have elevated Rafael Grossi, director-general of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), to the status of a heroic figure. He is depicted as a courageous and resolute leader, capable of cutting through the geopolitical chaos and institutional paralysis that often hinder global nuclear oversight.

-

Brig. Gen. Elhami appointed as Iran’s Air Defense Chief

TEHRAN – Iran has appointed Brigadier General Alireza Elhami as the new commander of the Army Air Defense Force.

-

Iran and the ethics of power - a civilisational rebalancing of world politics

GOA – The contemporary international order is showing unmistakable signs of moral fatigue. The promises that once accompanied global power—democracy, stability, prosperity—now ring hollow across vast regions of the world.

Sports

-

Sepahan beat Foolad: 2025/26 PGPL

TEHRAN – Sepahan football team edged past Foolad 1-0 in the 2025/26 Iran Persian Gulf Professional League (PGPL) on Monday.

-

Fatemeh Sharif takes charge of Pakistan women’s futsal team

TEHRAN - The Pakistan Football Federation (PFF) on Sunday confirmed the appointment of Fatemeh Sharif Noghabi as the head coach of its national women’s futsal team.

-

Persepolis edge Aluminum at 2025/26 PGPL

TEHRAN – Persepolis football team edged past Aluminum 1-0 here on Sunday at the 2025/26 Iran’s Persian Gulf Professional League (PGPL).

Culture

-

Two Iranian films win at 28th Olympia International Film Festival

TEHRAN – Two Iranian short films were among the winners at the 28th Olympia International Film Festival for Children and Young People, which was held in Pyrgos, Greece, from November 29 to December 12.

-

Iran participating in 42nd Istanbul International Book Fair

TEHRAN – Iran has participated in the 42nd Istanbul International Book Fair, held under the theme “The Many Moods of Literature,” which opened on December 13 and will continue until December 21, at the TÜYAP Exhibition and Congress Center.

-

Tehran Symphony Orchestra unveils "Whispers Within" concert with classical, contemporary works

TEHRAN- Tehran Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Nasir Heidarian, will present its latest concert titled " Whispers Within" at Tehran’s Vahdat Hall on Thursday and Friday.

Economy

-

Cabinet approves general outline of next year’s budget bill

TEHRAN – Iran’s cabinet on Sunday approved the general framework of the government’s budget bill for the Iranian year 1405 starting late March 2026, during a meeting chaired by President Masoud Pezeshkian.

-

Oil Ministry targets completion of over 1,000 km of gas pipelines by late Mar. 2026

TEHRAN – Iranian Oil Ministry aims to complete and bring into operation more than 1,000 kilometers of gas transmission pipelines by the end of the current Iranian calendar year (late March 2026), Oil Minister Mohsen Paknejad said, underscoring efforts to strengthen energy security during periods of peak demand.

-

Iran, Pakistan push for joint trade committee, $10b trade target

TEHRAN – Iranian and Pakistani business representatives agreed to pursue the creation of a joint trade committee and work towards boosting bilateral trade to $10 billion, during a meeting in Karachi aimed at strengthening private-sector cooperation and facilitating cross-border commerce.

Society

-

Iran ready to foster tech ties, share expertise with Ethiopia

TEHRAN – The head of the Organization for the Development of International Cooperation in Science and Technology, Hossein Roozbeh, has announced the country’s readiness to share knowledge and boost technological cooperation with African countries, particularly Ethiopia.

-

Expo of creative, knowledge-based firms to focus on AI

TEHRAN – The fourth exhibition showcasing the achievements of creative and knowledge-based companies is scheduled to take place from December 28 to 31 in Tehran, with a focus on artificial intelligence (AI).

-

WFP releases November report on Iran

TEHRAN – The World Food Program (WFP) has released a report, expounding on activities in Iran over the month of November.

Tourism

-

Iran’s Khoy and Turkey’s Konya sign sister-city agreement

TEHRAN - The Iranian city of Khoy and Turkey’s Konya have signed a sister-city agreement, committing to expand cooperation in spiritual tourism, cultural exchanges, urban management and sustainable infrastructure development, officials said.

-

Zoroastrian lawmaker highlights restoration of historic fire temples

TEHRAN — An Iranian lawmaker representing the Zoroastrian community has called for continued restoration and protection of historic fire temples in the central province of Isfahan.

-

Iranology goes beyond academia, Armenian researcher says

TEHRAN—Iranology is a quiet diplomacy between Iran and Armenia. Mariam Zazyan, an Armenian Iranologist, believes that being an Iranologist has a responsibility beyond academic study and can play an effective role in strengthening the cultural and friendly relations between the nations.

International

-

Israel’s media war fails to divide Iran and Lebanon

TEHRAN – Israeli media and their affiliates recently tried to stir the pot, spotlighting a brief back-and-forth between Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi and his Lebanese counterpart Youssef Raggi, in an effort to paint the two countries as being at odds.

-

Lebanon at the edge: Diplomacy between fire and restraint

BEIRUT—Lebanon has entered a critical moment. An intense flurry of regional and international contacts is unfolding against the backdrop of open Israeli threats against Lebanon and mounting internal pressure.

-

38 years after the founding of Hamas

TEHRAN – Hamas affirms that Operation al-Aqsa Flood marked a pivotal moment in the Palestinian people’s struggle against occupation.

Video Comment

-

Ayatollah Khamenei’s vision of freedom and humanity discussed in intl. conference

-

Iran hosts SCO joint anti-terror drills

-

Holy Mary Metro Station marks interfaith unity in Tehran

-

Academics analyze social dimensions of Resistance in Tehran conference

-

Culture minister highlights year of progress in arts, global image enhancement

Most Viewed

-

Australia’s tragedy won’t wash Netanyahu’s bloody hands

-

Afghanistan’s neighbors gather in Tehran to coordinate support for the war-torn country

-

Iran’s free zones attract $461m in foreign investment in 8 months

-

Israel’s misstep and the resilience of Iran’s strategic autonomy

-

Iranian students shine at World Mathematics Team Championship 2025

-

What Iran’s foreign ministry spokesman said at his weekly briefing

-

Hezbollah’s move in launching Women’s Action Unit marks a milestone

-

Full Israeli-US support for opposition and terrorist groups

-

“Where’s Daddy?”: How Israel and US tech turn Gaza’s homes into graves

-

Tehran hosting intl. transport, logistics exhibition

-

Professor faults Kabul for failure of Pakistan-Afghanistan peace talks

-

Maritime-oriented economy a unique opportunity for Iran: PMO head

-

Navy commander says readiness being boosted in line with emerging threats

-

An inside look at Gorgan’s tribal festival

-

Culture ministers of Iran, Kazakhstan sign MoU on cinematic cooperation