Islamic Republic of Iran changed the laws of psychology of nationalism: prof.

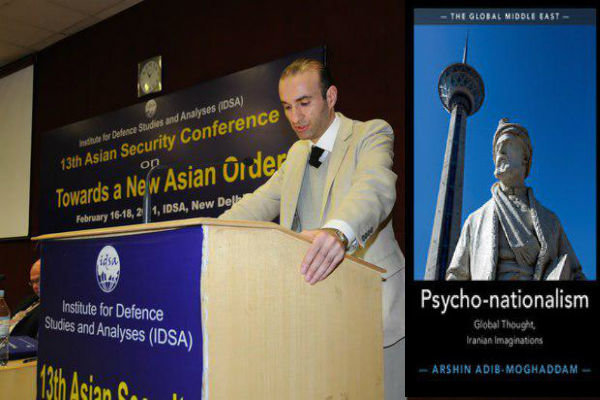

TEHRAN - Professor Arshin Adib-Moghaddam, Chair of the Centre for Iranian Studies at the London Middle East Institute believes “no philosopher or social scientists can disregard the importance of Iran as an analytical object.”

Professor in Global Thought and Comparative Philosophies and Chair of the Centre for Iranian Studies at the London Middle East Institute, also adds that “In western scholarship there is more emphasis on “baby nations” such as Canada and the United States. Obviously, this is because of the political economy of the social sciences which is primarily produced in the so called “west”, not least because of academic restrictions in the “east””

He adds that “This has had the regrettable effect that Iran is not studied conceptually, as a case that tells us a lot about universal dynamics in global history.”

Here is the full text of the interview:

Q: You have recently written a book entitled "Psycho-nationalism, Global Thought, Iranian Imaginations" which was published by Cambridge University Press. What was the necessity behind it?

A: Allow me to take this opportunity to wish fellow Iranians inside and outside of the country a happy new year. Norouz stands for an umbilical cord between Iran and the world. The metaphors and symbols that embellish the festivities of this season stand for a culturally unique symbol for peace and understanding all over the world.

The emphasis on renewal which fills this season with so much beauty reflects the essential desire of humanity to thrive for peace and harmony, both within ourselves and with the world. In this sense Norouz is also a philosophy of life - an antidote to hegemony, domination and all nefarious forms of power. This is why I signed the letter to the UN General Secretary Guterres that the Tehran Times published. Norouz is the spirit within a world without spirit.

This idea of resisting forms of domination is at the heart of my work. My most recent book Psycho-nationalism is a good example for my humble efforts to break down systems of power and to show how they are assembled as a means to dominate our thinking and behaviour. I have invented the term “psycho-nationalism” to show that forms of ultra-nationalist thinking all over the world assault our psychology and cognition. We experience the nation immediate after saying Mum or Dad. Once we enter the social world, and develop a social consciousness, psycho-nationalism lodges into our minds. The concept of psycho-nationalism is universally applicable. Iran is a hard case to understand these dynamics because it is what Eric Hobsbawm correctly called one of the few “historic nations” of human history. And to understand psycho-nationalism means to understand, the self, the other, us and them. It is essential for any understanding of politics and identity, both in its individual manifestation and its national projection. None of the Iranian intellectuals in the past and present have deconstructed these psychological dynamics without, at the same time, trying to present an alternative, ideologically and politically hegemonic counter-model. This was the mistake of Kermani. Akhundzadeh and others at the beginning of the 20th century on the one side, and al-e Ahmad, Shariati and Fardid at the end of the 20th century on the other side of the ideational spectrum.

Q: What was your main question in this book?

A: Psycho-nationalism stands for an immensely dense assemblage. These massively intrusive machines of indoctrination try to control the way we think about our identity, our place in the world and the place of others. I conceptualise these themes with reference to Iran, given that “Persia” has been produced as an idea and reality since the beginning of history. Hence no philosopher or social scientists can disregard the importance of Iran as an analytical object. In western scholarship there is more emphasis on “baby nations” such as Canada and the United States. Obviously, this is because of the political economy of the social sciences which is primarily produced in the so called “west”, not least because of academic restrictions in the “east”. This has had the regrettable effect that Iran is not studied conceptually, as a case that tells us a lot about universal dynamics in global history. My book tries to address this problem, by showing that nationalism in Iran precedes the western variant. Safavid psycho-nationalism, it is argued, was a very sophisticated form of nation-building which created its own problems for the meaning of Iran until today. No Iranian state, at least since the Safavids, has managed to invent a meaning of Iran, that would accommodate the beautifully complex, poetically diverse manifestations of the country’s genetic code. The picture of Iran can only be accommodated on a broad canvas that needs to be continuously extended to make space for the intrinsically global and transnational force that Persia has exuded in human history.

Q: It has zoomed in on Iranian identity and political and psychological roots of national identity. Also, you compared and contrasted Iran both before and after revolution. First, what constituted Iranian national identity in both periods mentioned above? And then, do you think that these elements (nationalist attitudes) enjoyed any kinds of transformations both pre- and pro- 1979 revolution?

A: Psycho-nationalism charters the changes in the myth making apparatus that has delivered meanings about Iran in recent history. The content of the identity politics has been different, the purpose and mechanisms are comparable. The carrier of psycho-nationalism has been the state – both before and after the revolution a meaning of Iran was created that catered for the sovereignty of a very particular interpretation of Iran and the legitimacy of the power structures that were built by the governments in place. None of them pacified the dialectic between state and society in Iran, exactly because of the blind-spots that these dynamics created. None of these issues are discussed from a normative perspective by me. The approach is purely analytical. Before the revolution the sovereignty of the state, and the legitimacy claimed by the monarch were based on an idea of Iran as “Aryan”, “Western”, even French as the Shah put it in an article for Life Magazine in the United States. Psycho-nationalism before the revolution was carried by weak institutions and a warped ideology that did not encompass the complexity of the Iranian existence in human history. The revolution was a massive explosion that ripped apart this monarchic sovereignty and its psycho-nationalist precepts once and for all. The revolution of 1979 nuked the monarchy on a cellular level – it was the massive outcry of a people intoxicated by the utopia for a better tomorrow. There will never be anything comparable in world history.

After the revolution the content and institutional make up of Iranian psycho-nationalism changed, but the mechanisms are comparable. The idea of the state and its identity, once institutionalised, remained confined. Again there is no normative position here. If the meaning of Iran would have been fortified in the state building process with minimal psycho-nationalist stealth, there would be less resistance. Where there is psycho-nationalism, there will always be recurrent resistance. This is an important mnemonic – a law that can’t be changed by new mechanisms of power.

Q: You made use of "Psycho-Nationalism" as a theoretical approach for the study of Iranian identity. Why did you do that? Also, is "Psycho-Nationalism" able to present a comprehensible outlook of Iranian national identity, governance methods and Iranian culture?

A: No theory can fully explain everything. Grand theory in the Hegelian tradition, from Marx to Freud has been partially exposed for the chalantry that it inspired. In particular, Freudian psycho-therapy has destroyed many lives until today. Psychology remains one of the most dangerous pseudo-sciences out there. It serves a global pharmaceutical capitalism that controls human beings in quite a direct manner. And of course we know what Marxism did to human history. Not that Marx was a bad person, but he lived through a time when the laboratories of the so called western “enlightenment” created the hubristic notion that everything can be changed with the power of revolution. After hubris, there is nemesis in the ancient philosophical tales of the Greeks which were so beautifully reinterpreted and extended by Ibn Sina, Farabi and Averroes whose deep philosophy reveals a commitment to critical thinking that is exemplary in global thought.

Good theory starts with the acknowledgement of the theorist about his or her own limitations. This is what I call critical theory which is more honest and yields better explanations than the positivist hubris that we are accustomed too, especially by mainstream American social scientists. Psycho-nationalism is a critical concept. It gives us tools to analyse and understand social phenomena by asking the “why” questions. Exactly because it is a concept which does not attempt to explain everything, it accommodates the modes of resistance to psycho-nationalism. The argument of the books is not confined to modes of power projection by the state – it is exactly about how power is resisted by society. In Iran this counter-discourse has matured for millennia and it is nestled in the labyrinthine corridors of Iranian poetry, art and philosophy. These forms of human endeavour are so far away from identitarian projects and the forms of power they intend to legitimate, that they fuel the human mind with the beautifully transcendent spirit that is lodged in every human being. I call this Insaniyat, in a close re-reading of Ali Shariati.

Leave a Comment