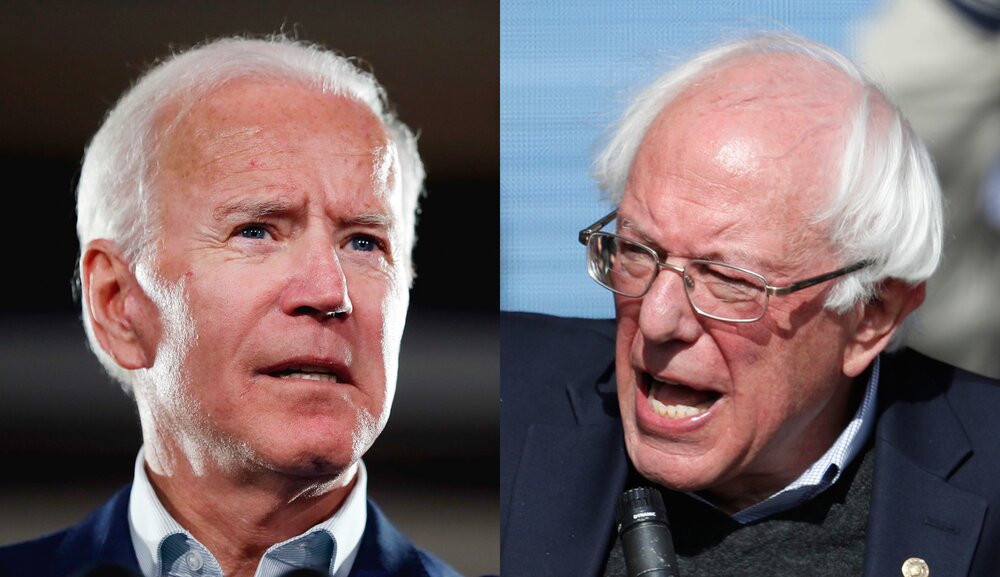

Sanders challenges Biden over Iraq war

The troubled mistake of the former vice president of U.S.

Former US Vice President Joe Biden's support for the Iraq war has become a big trouble for him. Many analysts believe that this could create a major crisis for Biden during the first phase of the Democratic primaries.

Biden, however, is trying to make things natural! In the 2016 presidential election, Hillary Clinton was criticized by many American voters for supporting the Iraq war.Here are some of the latest news and analyzes in U.S.:

- Sanders slams Biden, says he was ‘wrong big time’ on Iraq War

As Fox News reported, In some of his most forceful criticism to date against 2020 Democratic rival Joe Biden, Sen. Bernie Sanders said he has some “pretty significant” policy differences with the former vice president as he assailed his stances on trade, Wall Street regulation and more.And Sanders – the populist senator from Vermont who’s making his second straight White House run – said that Biden was “wrong big time” in voting in 2002 in support of the Iraq War.

In an interview Tuesday with the Washington Post, Sanders also slammed Republican President Trump over his controversial tweets directed at Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and three fellow first-term progressive lawmakers. He called Trump a “racist” and a “bigot.”

And the independent senator said that if elected to the White House, he would “absolutely” look into breaking up online giants Amazon, Facebook, and Google.Sanders was interviewed a day after Biden unveiled a plan to beef up the Affordable Care Act – better known as ObamaCare – by adding a “public option.”

Biden’s move is a bid to protect the signature 2010 law – which dramatically altered the nation’s health care system – not only from the decade-old attempts by the GOP to repeal the law, but also from calls from the Democratic Party’s left flank to replace it with "Medicare-for-all."

“I understand the appeal to Medicare-for-all. But folks supporting it should be clear that it means getting rid of ObamaCare. And I’m not for that,” Biden emphasized.

Sanders, firing back a day later, said “of course he’s wrong” regarding Biden’s insinuation that a single-payer Medicare-for-all system would tear up ObamaCare.And he said that “when Trump and his friends tried to repeal it, you’re looking at a guy who traveled all over this country, led large rallies, and worked with Democratic senators and members of Congress to oppose what Trump was doing.”

“I have helped write and defended the Affordable Care Act,” Sanders added.But he noted that “you know what – times change and we have to go further.”

“I like Joe and I hope we will have this debate, but when Joe says something to the effect that ‘Medicare for seniors’ -- what did he say -- will end,’ I mean that’s just obviously an absurd situation,” Sanders added.He explained that his Medicare-for-all plan would cost $30-40 trillion over a 10-year period. But he compared that to the $50 trillion he said it would cost to continue the nation’s current health care system.Sanders also slammed Biden for his vote in the 1990s as a senator from Delaware in favor of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), as well as his initial support for the Iraq War. Biden has long admitted that his 2002 Iraq War vote was a mistake.And Sanders targeted Biden for his votes to deregulate Wall Street, which he noted he opposed.“That led in my view to the Wall Street collapse of 2008 and the incredible pain that that caused for the American people,”

Sanders noted.And he argued that “the differences between Joe and me on foreign policy, on domestic policy, is pretty significant. More importantly, our vision for the future of this country is very different and voters will end up taking a look at our records, at our ideas for the future. They’ll make their decision.”

Sanders also took aim at the president over his language – both on Twitter and in front of cameras at the White House – slamming Ocasio-Cortez and fellow Democratic freshman Reps. Ilhan Omar of Minnesota, Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts and Rashida Tlaib of Michigan.In comments that Democrats have called racist, Trump said that if the lawmakers “hate our country,” they can go back to their “broken and crime-infested” countries, fix them and then "come back and show us how it's done."“If you’re not happy in the U.S., if you’re complaining all the time, you can leave, you can leave right now,” he said.

Three of the four lawmakers were born in the United States.“We have a president of the United States who is a racist, who is a bigot,” Sanders emphasized. “This is disgusting. This is the most racist outbreak statements from a president that I’ve heard in my life and it must be universally condemned.”

In the interview, Sanders also said if elected, he would probably not move the U.S. embassy to Israel from Jerusalem back to Tel Aviv.Sanders, 77, was asked if his age was a factor in the 2020 election. He noted that it was one of many factors, but also said that he’s “blessed with good health.”Explaining he used to run long distance as a younger person, he jokingly challenged the 73-year-old president, saying “I will run a mile with Donald Trump.”

- Joe Biden Was One of the Iraq War’s Most Enthusiastic Backers

As Branko Marcetic wrote in Jacobin Mag , Joe Biden didn’t just vote to invade Iraq — he worked hard alongside George W. Bush to persuade the public to back it. Biden holds significant responsibility for the bloodshed that has engulfed Iraq and the surrounding region since the invasion.

As the Trump administration’s saber-rattling toward Iran threatens another disastrous war in the Middle East, foreign policy has gained newfound focus in the 2020 presidential race. And former vice president Joe Biden’s 2002 vote in favor of the Iraq War leaves him with a particularly glaring vulnerability.Biden’s vote had already become a sticking point in the race before President Trump began his provocations toward Iran in earnest. Bernie Sanders has used Biden’s record to draw a contrast with his own opposition to the Iraq War. Rep. Seth Moulton, another 2020 candidate, has called for Biden to admit he was wrong for casting the vote. And a recent POLITICO/Morning Consult poll showed more than 40 percent of respondents between eighteen and twenty-nine were less likely to back Biden because of it.

But to say the now–Democratic front-runner voted for the Iraq War doesn’t fully describe his role in what has come to be widely acknowledged as the most disastrous foreign policy decision of the twenty-first century. A review of the historical record shows Biden didn’t just vote for the war — he was a leading Democratic voice in its favor and played an important role in persuading the public of its necessity and, more broadly, laying the groundwork for Bush’s invasion.

In the wake of September 11, Biden stood as a leading Democratic voice on foreign policy, chairing the powerful Senate Foreign Relations Committee. As President Bush attempted to sell the US public on the war, Biden became one of the administration’s steadfast allies in this cause, backing claims about the supposed threat posed by Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein and insisting on the necessity of removing him from power.

Biden did attempt to placate Democrats by criticizing Bush on procedural grounds while largely affirming his case for war, even as he painted himself as an opponent of Bush and the war in front of liberal audiences. In the months leading up to and following the invasion, Biden would make repeated, contradictory statements about his position on the issue, eventually casting himself as an unrepentant backer of the war effort just as the public and his own party began to sour on it.

- From Dove to Hawk

Biden hadn’t always been a hawk on Iraq. He had voted against the first Gulf War in 1991, though even his opposition to that war had been tepid at best, focused mainly on badgering George H. W. Bush into having Congress rubber-stamp a war Bush had already made clear he was intent on waging with or without its approval.In 1996 Biden criticized Republican claims that then-president Bill Clinton wasn’t being tough enough on Iraq amid calls to remove Saddam Hussein from power, labeling an ouster “not a doable policy.”

Before the War on Terror drove US foreign policy, Biden criticized Bush during his first year in office for the then-president’s hawkish position on missile defense.

September 11 changed all this. Only one day before the attacks, at a speech in front of the National Press Club, Biden had called Bush’s foreign policy ideas “absolute lunacy” and charged that his missile defense system proposal would “begin a new arms race.” But the nearly 3,000 Americans who were killed on US soil that day upended the political consensus. Bush’s approval rating shot up to a historic 90 percent, and any elected officials who failed to match the president’s zeal for military retribution became vulnerable to accusations of being “soft on terror.”

“Count me in the 90 percent,” Biden said in the weeks after the attack. There was “total cohesion,” he said, between Democrats and Republicans in the challenges ahead. “There is no daylight between us.”

In November 2002, just a little over a year following the World Trade Center attacks, Biden faced reelection amidst a political climate in which the Bush administration had incited nationalist sentiment over the issue of terrorism. In October 2001, Biden had been criticized in Delaware newspapers for comments that were perceived as potentially weak, warning that the United States could be seen as a “high-tech bully” if it failed to put boots on the ground in Afghanistan and instead relied on a protracted bombing campaign to oust the Taliban.Consequently, Biden, then deemed by the New Republic as the Democratic Party’s “de facto spokesman on the war against terrorism,” quickly became a close ally of the Bush administration in its prosecution of that war. The White House installed a special secure phone line to Biden’s home, and he and three other members of Congress met privately with Bush in October 2001 to come up with a positive public relations message for the war in Afghanistan.

Biden’s stance on Iraq soon began to change, too. In November 2001, Biden had batted away suggestions of regime change, saying the United States should defeat al-Qaeda and Osama bin Laden before thinking about other targets. By February 2002, he appeared to have creaked opened the door to the possibility of an invasion.“If Saddam Hussein is still there five years from now, we are in big trouble,” he told a crowd of 400 Delaware National Guard officers that month at the annual Officers Call event.“It would be unrealistic, if not downright foolish, to believe we can claim victory in the war on terrorism if Saddam is still in power,” he said around the same time, echoing the language of hawks like Connecticut Sen. Joe Lieberman.

Biden soon developed the position he would hold for the following thirteen months leading into Bush’s March 2003 invasion of Iraq: While the Bush administration was entirely justified in its plans to remove Hussein from power in Iraq, it had to do a better job of selling the inevitable war to the US public and the international community.“There is overwhelming support for the proposition that Saddam Hussein should be removed from power,” he said in March 2002, while noting that divisions remained about how exactly that would be done. If the administration wanted his support, Biden continued, they would have to make “a complete and thorough case” that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) and to outline what they envisioned a post-Hussein Iraq would look like.

It was a stance well calibrated for the political climate. Biden could continue to point to disagreements with the administration for liberal audiences, even if they were merely procedural, while putting his weight behind the ultimate goal of war with Iraq. At the same time, Biden’s apparent criticisms doubled as advice for the administration: If you want buy-in from liberals for your war, this is what you’ll have to do.

“I don’t know a single informed person who is suggesting you can take down Saddam and not be prepared to stay for two, four, five years to give the country a chance to be held together,” Biden recounted telling Bush privately in June 2002. It was a talking point he would repeat often over the next year, that regime change in Iraq was the correct thing to do, but would require a long-term commitment from the United States after Hussein’s removal.

- Setting the Ground Rules

During frequent television appearances, Biden didn’t just insist on the necessity of removing Hussein from power, but appeared to signal to the Bush administration on what grounds it could safely seek military action against Iraq.When Bush’s directive to the CIA to step up support for Iraqi opposition groups and even possibly capture and kill Hussein was leaked to the Washington Post in June, Biden gave it his approval. Asked on CBS’s Face the Nation if the plan gave him any pause, Biden replied: “Only if it doesn’t work.”

“If the covert action doesn’t work, we’d better be prepared to move forward with another action, an overt action, and it seems to me that we can’t afford to miss,” he added.

“Prominent Democrats endorse administration plan to remove Iraqi leader from power,” ran the subsequent Associated Press headline.

A month later in July, Biden affirmed that Congress would back Bush in a preemptive strike on Iraq in the event of a “clear and present danger” and if “the president can make the case that we’re about to be attacked.”

Asked on Fox News Sunday the same month if a discovery that Hussein was in league with al-Qaeda would justify an invasion, Biden replied: “If he can prove that, yes, he would have the authority in my view.”

“And this will be the first time ever in the history of the United States of America that we have essentially invaded another country preemptively to take out a leadership, I think justifiably given the case being made.”

These themes would be used by the Bush administration in the months ahead to sell the war to the American public. The nonexistent ties between Hussein and al-Qaeda became one of the most high-profile talking points for the war’s proponents. And the Bush administration would publicize the supposedly imminent threat Hussein posed to the United States, including then–national security advisor Condoleezza Rice’s infamous September declaration that “we don’t want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud.”

By July Biden appeared to rule out a diplomatic solution to the conflict. “Dialogue with Saddam is useless,” he said.

Leave a Comment