Persian translation of Koestler's “The Thirteenth Tribe” republished after 30 years

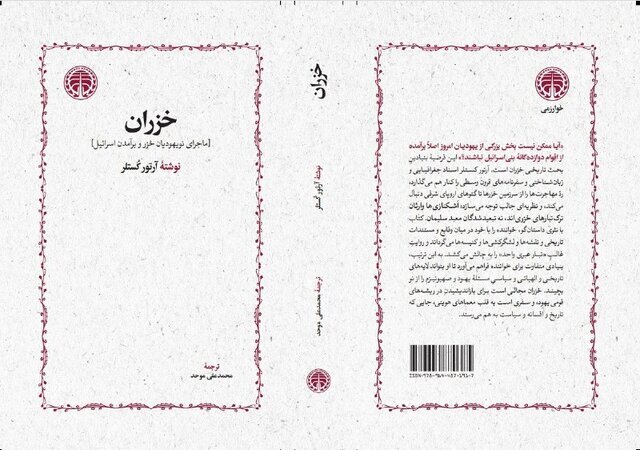

TEHRAN- A Persian translation of Hungarian author and journalist Arthur Koestler’s 1976 book "The Thirteenth Tribe: The Khazar Empire and its Heritage", by Iranian translator and scholar Mohammad Ali Movahed, has been republished 30 years after its initial release.

Published by Kharazmi Publications in Tehran, the book was rendered into Persian by Movahed in 1982 based on the English edition.

In the preface, Movahed writes: "The name 'Khazar' evokes the story of a doomed people who resided across the Caspian Sea, in regions now part of the former Soviet Union. Historically, they held courts with golden thrones—symbols of importance and respect—and had interpreters familiar with the Khazar language and script, reflecting extensive diplomatic relations. This restless, warlike, and often troublesome people were constantly enticed by the Byzantine Empire (Rome), repeatedly attacking cities in Aran, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. At one point, their incursions reached as far as Hamedan in Iran’s heartland. The Sassanid kings built fortifications across the Caucasus to guard against surprise attacks. The Khazars resisted the Islamic advance, and after many of their Turkic kin converted to Islam, they turned to Judaism.”

“The Thirteenth Tribe” is a highly controversial and widely discredited book that introduces the Khazar hypothesis of Ashkenazi Jewish origins. Koestler’s central claim is that the majority of Ashkenazi Jews do not descend from the ancient Israelites and Judeans of biblical times, but rather from the Khazars, a Turkic people who, according to his thesis, converted en masse to Judaism in the 8th century. He further argued that following their conversion, the Khazars migrated westward into Eastern Europe during the 12th and 13th centuries, as their empire was collapsing, shaping the Jewish communities in that region.

Koestler’s hypothesis draws on a limited set of historical sources, notably works by scholars such as Douglas Morton Dunlop, Raphael Patai, and Abraham Polak. His primary aim was to challenge the racial and biological notions of Jewish identity that fueled antisemitism. Koestler believed that if he could demonstrate that Ashkenazi Jews primarily descended from the Khazars—who were Turkic and not Semitic—then the racial basis for antisemitism would be undermined, potentially eradicating one of its main ideological justifications. He sought to shift the narrative from racial genetics to cultural and historical identity, hoping to promote a more inclusive understanding of Jewish origins.

However, the scholarly community has largely rejected Koestler’s claims. Critics argue that his research was superficial and relied heavily on speculative interpretations. Many historians and geneticists contend that Koestler’s sources, such as Dunlop’s “History of the Jewish Khazars”, are tentative at best and do not provide conclusive evidence of a Khazar origin for Ashkenazi Jews. Genetic studies conducted in recent decades have overwhelmingly shown that Ashkenazi Jews share common ancestry with other Jewish populations and are genetically linked to Middle Eastern groups, challenging the core of Koestler’s hypothesis. Leading scholars like Peter Golden and Moses Shulvass have dismissed the Khazar theory as lacking solid evidence and containing sweeping, unsupported claims.

Koestler’s motives are believed to be rooted in a desire to combat antisemitism. Biographer Michael Scammell reports that Koestler told French biologist Pierre Debray-Ritzen that his goal was to demonstrate that if Ashkenazi Jews descended from Khazars rather than biblical Israelites, then racial antisemitism would lose its foundation. Some scholars suggest that Koestler was also motivated by an interest in reconciling Jewish history with a broader cultural narrative that minimized racial distinctions.

Despite its initial attention, the book’s claims have faced widespread criticism. Many historians, geneticists, and scholars have dismissed it as pseudohistory. Nonetheless, the Khazar hypothesis has found a receptive audience among certain groups outside mainstream academia. In particular, some anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic factions have exploited the theory to deny Jewish historical claims to Israel. Arab states, including Saudi Arabia, have argued that if Ashkenazi Jews are primarily Khazar, then their claim to the biblical land of Israel is invalid. Extremist groups, such as neo-Nazis and Christian Identity followers, have embraced and promoted the Khazar theory, viewing it as evidence to undermine Jewish legitimacy.

Jeffrey Kaplan notes that organizations promoting white nationalism and conspiracy theories have used Koestler’s work to reinforce their narratives. The neo-Nazi magazine “The Thunderbolt” called “The Thirteenth Tribe” “the political bombshell of the century,” and the theory continues to circulate among extremist circles.

SAB/