How is Washington’s oil-first strategy redrawing Libya’s geopolitical map?

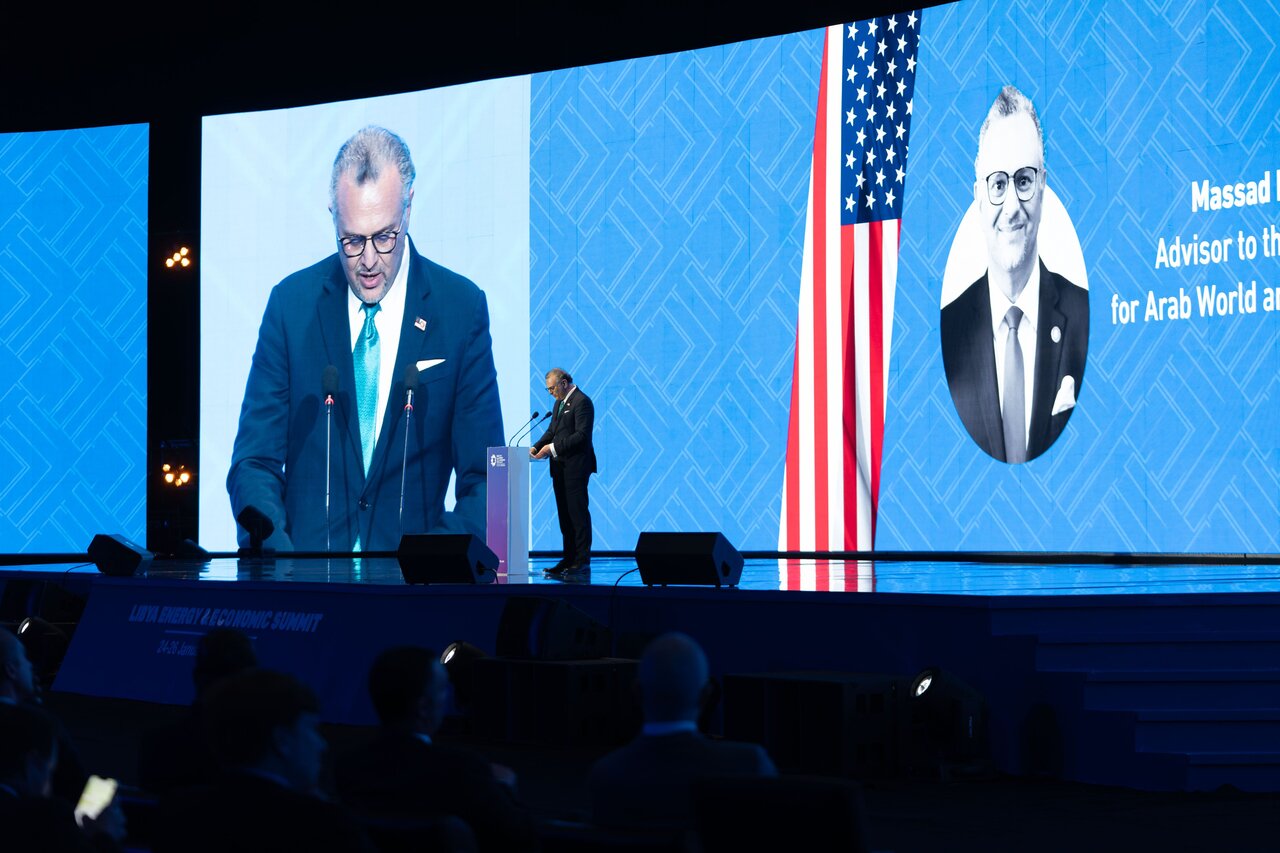

BEIRUT — The recent visits of Massad Boulos, adviser to U.S. President Donald Trump for the Middle East and African affairs, to Tripoli and Benghazi have ignited intense debate inside Libya.

The controversy deepened after the signing of a long-term oil agreement on the sidelines of the Tripoli Energy Summit, involving France’s TotalEnergies and the American giant ConocoPhillips, with foreign investments exceeding $20 billion.

While Washington frames these moves as support for unity and stability, many Libyans see them as a source of growing anxiety rather than reassurance.

In a post on X, Boulos described his meeting with Prime Minister Abdulhamid Dbeibah as “productive,” stressing that unity and stability are essential to attract American investment. Yet this language, centered on investment rather than legitimacy, has raised suspicions about US priorities in a country still lacking an elected government.

Two governments, one oil prize

Libya remains divided between two rival authorities. In the west, the internationally recognized Government of National Unity, led by Dbeibah, governs from Tripoli. In the east, a parallel administration appointed by the House of Representatives and led by Osama Hammad operates from Benghazi, backed by Khalifa Haftar’s forces and controls much of eastern and southern Libya.

Since 2011, this split has paralyzed state institutions and transformed oil wealth into a tool of political survival rather than national development.

Against this backdrop, Boulos’ meetings with both camps—including his encounter with Belqasim Haftar, head of the Development and Reconstruction Fund in the east—have reinforced the perception that Washington is dealing with Libya as two separate markets rather than a single state.

Analysts argue that Boulos’ approach effectively entrenches division. By concluding economic understandings with all parties, Washington strengthens each faction within its own territory.

Instead of encouraging compromise, these deals convince rival elites that they can bypass unity altogether while still enjoying international backing.

The result, analysts warn, is a hardened political stalemate dressed up as pragmatic diplomacy.

The Libyan Political Parties Coordination echoed this concern, stating it views Boulos’ meetings “with suspicion,” accusing them of recycling the same political figures and excluding broader Libyan participation.

Such selective engagement, the group warned, deepens division and prolongs the transitional phase rather than ending it.

Other observers offer a sharper critique; they don’t deny that Washington seeks to unify Libyan institutions—but argue that the objective is strategic control, not reconciliation.

From their perspective, Washington aims to consolidate Libya’s oil, financial, and security institutions under an American-friendly framework.

This would serve two strategic goals: pushing Russia out of the Libyan arena and securing privileged access to one of Africa’s largest oil reserves.

With confirmed reserves of around 48.4 billion barrels, Libya is too important to ignore, particularly amid global energy uncertainty. It is no coincidence that most agreements linked to Boulos’ visits focus on oil, gas, refining, and production optimization.

The American approach does not stop at energy; Boulos also met military leaders from both east and west, praising joint US-supervised military exercises planned in Sirte.

Officially, these maneuvers are framed as confidence-building measures. In reality, they reflect a deeper logic: protecting oil infrastructure and investment corridors.

This merging of economic and security tracks reveals the essence of Washington’s strategy: Stability is defined not by elections or constitutional order but by the uninterrupted flow of energy and the containment of rivals.

As long as Dbeibah and Haftar cooperate economically, their political rivalry can remain unresolved.

Another sensitive dimension is Libya’s frozen assets abroad, estimated to be worth up to $70 billion.

Reports suggest that Tripoli sought US mediation to ease restrictions on these funds in exchange for channeling investments through American companies.

While no comprehensive agreement has been finalized, the message is clear: access to Libya’s own wealth may come with political and commercial conditions.

Observers also warn that this raises profound ethical and legal questions: Without an elected government, who has the right to negotiate such assets? And why should American firms be privileged over others?

Meanwhile, the United Nations efforts to organize elections and reunify Libya have repeatedly stalled as Washington’s approach increasingly sidelines this track, favoring what analysts describe as an “economic–military” model of conflict management.

Elections, constitutional reforms, and popular legitimacy are pushed aside in favor of technocratic arrangements that keep the system functioning—but fragmented.

Libya’s crisis now appears less like a diplomatic failure than a carefully maintained equilibrium. A divided country that exports oil, welcomes American companies, and limits Russian influence is acceptable—perhaps even preferable—to Washington.

For Libyans, however, this model offers no sovereignty, no accountability, and no future shaped by the ballot box. Without legitimacy, unity becomes a slogan, and stability becomes a commodity—profitable for outsiders, but hollow at home.