The rise of sovereign voices after decades-old persistence of a Western monologue

For centuries, the relationship between what is conventionally called “the West” and the rest of the world has been narrated as a monologue.

A single voice—shaped by Europe’s industrial and philosophical revolutions and later amplified by the geopolitical power of the United States—has defined the terms of progress, modernity, sovereignty, and international morality. That monologue, often presented as a benign universalism, has in practice functioned as a project of cultural and political assimilation.

Today, however, that narrative is beginning to fragment. A chorus of previously silenced or disregarded voices is gaining prominence, coherence, and intellectual sophistication. This is not a visceral rejection of the established order but the articulation of alternative worldviews, confident enough to challenge hegemonic narratives and assert legitimacy on the global stage.

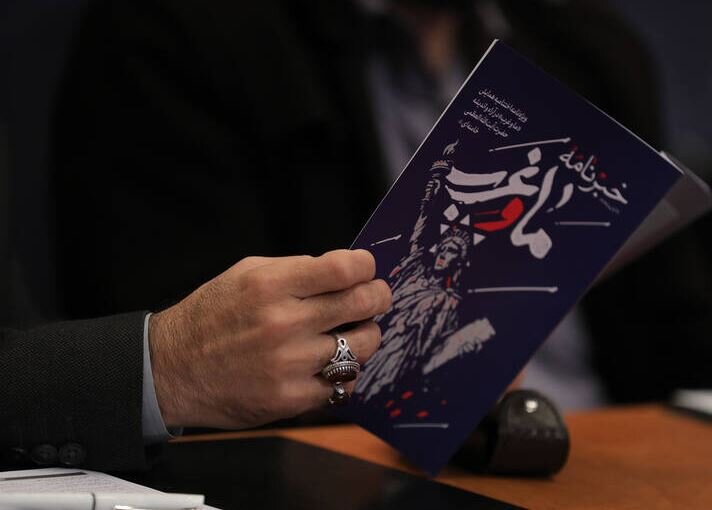

The recent “West and Us” conference, held in Tehran, should not be seen as a mere academic gathering. It represents a tangible manifestation of an intellectual shift reshaping global debate. Far from confrontational rhetoric, the event functioned as a forum for high-level reflection, examining the assumptions underpinning contemporary Western thought and exploring the conceptual foundations of a potentially more plural international order, not only in the distribution of power but in the production of ideas.

The starting point of the conference was a critique of Western universalism. Speakers argued that so-called universal values—liberal democracy, human rights interpreted through a specific lens, and secularism as the inevitable horizon—are in fact historically and culturally situated constructs. Their elevation to global norms does not reflect philosophical consensus but the extension of a power project.

This project, reaching its apex after the Cold War with the famous “End of History” thesis, relied on a binary logic: societies could be modern—i.e., Western—or remain anchored in tradition; alternative maternities were not acknowledged. What is emerging today, and what the conference sought to articulate with growing confidence, is precisely the pursuit of that “third way”: a modernity based not on imitation but on the assertion of distinct civilizational frameworks.

The conference examined in detail how this conceptual framework has, in practice, justified military interventions, crippling economic sanctions, and systematic interference in the internal affairs of sovereign states. Yet the debate went beyond conventional geopolitical critique. It ventured into epistemology: from what authority can the West—whose own institutions show signs of fatigue and structural crisis—claim the right to define the political and moral trajectory of the rest of the world?

Social polarization in the United States and Europe, tensions within continental integration projects, and the inability to respond effectively to global challenges have eroded the Western claim to universality. In this emerging vacuum, the periphery no longer seeks recognition but begins to assert its own voice. It is not a plea for permission to participate in history, but a reclamation of the capacity to write it.

Reclaimed agency: ‘Us’ as subject, not object

The term “Us” in the conference title is fundamentally epistemological. It is not a reactive or victimized “Us,” but a historical subject claiming the right to think and define itself from its own experience. This “Us” refers primarily to the Iranian civilization—with a cultural and intellectual continuity spanning millennia—capable of engaging with the West on equal terms rather than in subordination. Yet the pronoun extends beyond Iran, encompassing those societies that have historically been objects, rather than interlocutors, of Western homogenizing projects.

The emerging proposition is not one of naive isolation, but of genuine dialogue between civilizations—dialogue that can only exist among sovereign voices, not between translators and the translated. Hence the critique of what one speaker termed “coercive translation”: the requirement that all political or moral aspirations be expressed within Western conceptual and legal frameworks to be considered legitimate. The question arises: can notions of Islamic social justice, or systems of governance rooted in religious authority—such as Velayat-e Faqih—be comprehended through the categories of Rousseauian social contract theory? The answer, nuanced as it was, is no. These are distinct rationalities, each with internal logics and legitimacy criteria.

Within this framework, the Islamic Republic of Iran presents itself not as a model to export but as a case study: an example of institutional resilience in the face of four decades of sanctions, isolation, and military pressure. Its endurance is read as the expression of a collective political will that has developed a form of governance coherent with its history and civilizational identity. It is not a closed alternative, but empirical proof that other paths—non-Western, non-liberal—are possible.

The horizon of a multipolar world: From geopolitics to geoculture

The dominant Western discourse tends to interpret the rise of powers such as China or Russia as merely a rebalancing of power. The “West and Us” conference argued that what is unfolding is a far deeper shift: the transition from strategic multipolarity to genuine cultural multipolarity. It is not merely a redistribution of economic or military power but a redefinition of the normative and symbolic frameworks that have underpinned the international order since 1945.

From this perspective, new architectures of cooperation—such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the expanded BRICS, or connectivity corridors promoted by China and Iran—represent more than pragmatic agreements. They are attempts to construct an alternative geoculture, with their own languages of legitimacy, security mechanisms, and development standards. Spaces where Western influence is limited and principles such as non-interference, sovereignty, and respect for internal diversity prevail.

Iran, positioned geopolitically between Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the Persian Gulf, conceives itself as a key node in this emerging network. Its experience in navigating external pressures provides a form of political capital: the capacity to act as a mediator between civilizations rather than merely as a peripheral actor.

This is not, however, a utopia of global harmony. The vision articulated in Tehran recognizes conflict and competition as inherent to the international system. What it proposes is a demoralization of power, a break from the idea that any single civilization can claim moral superiority. In this new scenario, interactions between civilizations are understood less as struggles for dominance and more as negotiations among different rationalities.

Ultimately, the conference functioned as an intellectual laboratory. Its purpose was not to prescribe dogma but to cultivate an elite capable of thinking independently of inherited Western frameworks: of constructing original narratives, setting shared priorities, and forming alliances based on strategic affinity rather than ideological adherence.

Resistance as a strategic and ethical concept

Few concepts better encapsulate contemporary Iranian political logic than Resistance (Moqavemat). At the conference, this term was treated not as an ideological slogan but as an integral strategic doctrine, structuring sovereignty across military, economic, cultural, and technological dimensions. Its strength lies precisely in this breadth: Resistance is not the negation of power, but an alternative conception of it.

Economically, it manifests as a “resistance economy”, designed to reduce structural vulnerability to sanctions. This approach prioritizes self-sufficiency in strategic sectors, local technological innovation, and diversification of trade partners—essentially, turning survival into a program of endogenous modernization.

Culturally, Resistance is understood as a defense of symbolic space against global homogenization. Preserving education, media, and artistic systems from consumerist or morally relativistic pressures is framed as civilizational self-defense. The struggle is waged not only on battlefields or markets but within language, imagination, and narrative.

Technologically, this doctrine is particularly tangible. Iran’s nuclear and missile programs, often interpreted externally as military threats, were presented in Tehran as symbols of scientific autonomy, affirming the capacity of an isolated country to master advanced knowledge independently.

Together, these dimensions position Resistance as a principle of legitimacy. Material hardships—sanctions, blockades, shortages—are reframed as purposeful sacrifices, the moral cost of sovereignty. This narrative inversion—turning scarcity into political virtue—has allowed the system to project resilience and continuity even under severe pressure.

More than a defensive strategy, Moqavemat functions as an epistemology of power, a way of conceiving the world autonomously. Its effectiveness lies in its ability not only to resist coercion but to redefine what it means to resist.

Events like the “West and Us” conference can be read as a reflection of a long-term historical realignment. The era of uncontested Western hegemony appears to be drawing to a close. What is emerging is not necessarily an anti-Western order but a post-Western world, in which history is no longer written from a single center or dictated by one grammar of power.

For Western powers, the challenge is to listen to these new voices not as distorted echoes of their own thought or threats to be contained, but as legitimate participants in a global conversation that, for the first time in centuries, is genuinely plural.

For Iran—and for other civilizations asserting intellectual and political autonomy—the challenge is equally demanding: to translate resistance into effective governance, demonstrating that sovereignty and national dignity can coexist with social justice, material prosperity, and technological innovation. The legitimacy of the emerging order will ultimately depend on its capacity to deliver tangible results, not just narratives of emancipation.

The conference offered no simple answers, but it reframed the debate. The future will not be a mere continuation of the Western present; it will be the product of a prolonged and complex negotiation between competing worldviews—each with its own memory, its own scars, and its own claim to universality.