-

2025-11-19 22:20

2025-11-19 22:20

By Soheila Zarfam

Why is Trump lying about talks with Iran?

TEHRAN – While speaking to reporters during his Oval Office meeting with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, U.S. President Donald Trump told one lie and one half-truth about Iran. The lie was egregious, and the partial truth carried little persuasive weight.

-

By Sahar Dadjoo

International law has collapsed under great-power pressure, UN observer warns

Thomas G. Weiss says geopolitical paralysis has left the UN unable to restrain U.S.-Israel actions against Iran

TEHRAN – The recent 12-day U.S.-Israel assault on Iran has reignited debates about whether the global legal system retains any real authority or has collapsed under the weight of great-power politics. For Thomas G. Weiss, a leading thinker on international governance and long-time observer of the UN, the crisis is symptomatic of a much deeper breakdown.

-

By Sondoss Al Asaad

Washington pressuring Lebanon’s president and army

BEIRUT — Lebanon is grappling with an unprecedented political and diplomatic offensive targeting its highest institutions: the presidency and the army.

-

By staff writer

The strategic loom: Weaving Saudi Arabia into a U.S.-Israel framework

TEHRAN – The Tuesday meeting at the White House between U.S. President Donald Trump and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman was less about ceremony than about strategy.

-

By Wesam Bahrani

West Bank aggression fuels annexation fears

TEHRAN – Escalating violence and sweeping crackdowns across the West Bank intensify concerns over mounting Zionist territorial control.

-

Implementation begins for Iran’s new law supporting citizens abroad

TEHRAN – Iran has begun implementing a newly approved law designed to strengthen support for Iranians living overseas, after the president formally communicated the legislation to all relevant ministries and national institutions.

Politics

-

Panda or dragon? China’s strategy amid UN sanctions on Iran

TEHRAN- The snapback of pre-JCPOA UN sanctions against Iran have created a complex and delicate balancing act for China.

-

Tehran condemns UN Gaza resolution over violation of Palestinian rights

TEHRAN – Iran has expressed serious concern over the provisions of UN Security Council Resolution 2803 on Gaza, saying a major part of the resolution’s text runs counter to the legitimate rights of Palestinian people.

-

Oman marks National Day with celebration of stability and distinct national identity

Each year on this day, the Sultanate of Oman pauses before a sweeping historical canvas, commemorating the founding of the Al Bu Said state 281 years ago — the state that laid the foundations of a stable, prosperous, and regionally influential nation.

Sports

-

2025 Riyadh: Iranian runner Amirian takes gold

TEHRAN – Iranian runner Ali Amirian won a gold medal at the 2025 Islamic Solidarity Games (ISG) on Thursday.

-

Freestyler Amouzad wins gold: 2025 Riyadh

TEHRAN – Iranian freestyle wrestler Rahman Amouzad won a gold medal at the 2025 Islamic Solidarity Games (ISG) on Thursday.

-

Iran to play Indonesia at IFCPF Asia-Oceania Cup 2025 final

TEHRAN – Iran defeated Australia 4-0 in the IFCPF Asia-Oceania Cup 2025 semifinals on Thursday.

Culture

-

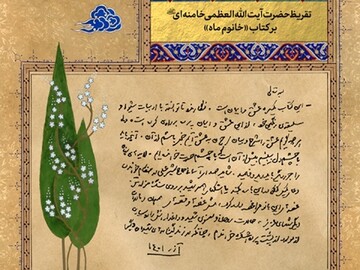

Leader’s commendation for “Lady Moon” unveiled in Shiraz

TEHRAN- On Wednesday, in tandem with Iran’s Book Week, the unveiling ceremony of the Leader of the Islamic Revolution, Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Khamenei’s commendation for the book "Lady Moon" was held at Vahdat Hall in Shiraz.

-

Tehran cultural center screens “Gifted”

TEHRAN- “Gifted”, a 2017 drama film by American filmmaker Marc Webb, went on screen at the Arasbaran Cultural Center in Tehran on Wednesday.

-

Resistance Theater Festival launches Nations section to promote global collaboration

TEHRAN- The 20th International Resistance Theater Festival has introduced a new section named Nations for its upcoming edition.

Economy

-

Tehran hosting major steel, metallurgy fair with over 700 exhibitors

TEHRAN – Tehran Permanent International Fairgrounds is hosting the 22nd edition of Iran's international exhibition of metallurgy, dubbed IRAN METAFO, bringing together more than 700 domestic and foreign companies in what officials describe as the country’s most significant annual gathering for the steel and metals sector.

-

IDRO launches Pilot overhaul program for aging industrial units in 6 provinces

TEHRAN – Iranian Industrial Development and Renovation Organization of Iran (IDRO) has begun a pilot program to renovate and modernize aging industrial units across six provinces, with officials saying nearly 200 factories have already registered to participate.

-

Iran to establish independent free-zone bank under new economic reform plan

TEHRAN - Iran plans to create an independent banking system dedicated to its free trade zones as part of a broader effort to overhaul the country’s economic governance, the economy minister said, adding that free zones will serve as the launchpad for structural reform.

Society

-

Young Scholars Club materializes Iran’s scientific diplomacy, superiority

TEHRAN - The Young Scholars Club was established in the Iranian year 1366 (1987-1988) to promote and expand basic sciences in the country.

-

COP30: Iran says climate action impossible without financing

TEHRAN – Sediqeh Torabi, an official with the Department of Environment (DOE), has emphasized the need for sufficient and predictable financing for implementing climate actions by developing countries.

-

First center for Caspian seal conservation inaugurated

TEHRAN – The first specialized center in the country for the conservation, treatment, and dissection of Caspian seals opened in Bojaq National Park in the Caspian Sea province of Gilan on Thursday.

Tourism

-

Iran ranks among top 10 countries for UNESCO-listed heritage: minister

TEHRAN – Iran ranks among the world’s top 10 countries in the number of UNESCO-inscribed heritage properties and elements, Minister of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts Seyyed Reza Salehi-Amiri said on Thursday during a visit to historical sites in Zanjan.

-

Echoes of the past: Unraveling the mystery of a Neolithic bone object

TEHRAN - A small, carefully crafted bone object from the Neolithic period, discovered at Yanik Tepe in East Azarbaijan province, northwest Iran, has intrigued both scholars and the public for decades.

-

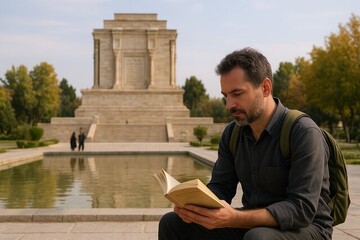

Khorasan Razavi has high potential for organizing literary, philosophical tours: researcher

TEHRAN--Given Iran's literary and philosophical history, especially in Khorasan Razavi, this province has high potential for organizing literary and philosophical tourism tours, a faculty member of Gorgan’s Hakim Jorjani Institute of Higher Education said.

International

-

Washington pressuring Lebanon’s president and army

BEIRUT — Lebanon is grappling with an unprecedented political and diplomatic offensive targeting its highest institutions: the presidency and the army.

-

The strategic loom: Weaving Saudi Arabia into a U.S.-Israel framework

TEHRAN – The Tuesday meeting at the White House between U.S. President Donald Trump and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman was less about ceremony than about strategy.

-

West Bank aggression fuels annexation fears

TEHRAN – Escalating violence and sweeping crackdowns across the West Bank intensify concerns over mounting Zionist territorial control.

Video Comment

-

Academics analyze social dimensions of Resistance in Tehran conference

-

Culture minister highlights year of progress in arts, global image enhancement

-

Gazan Journalists attacked by Israel

-

Brother of Iranian scientist murdered in Israeli strike speaks out

-

Footage shows Israel hit a kindergarten in Tehran

Most Viewed

-

Why is Trump lying about talks with Iran?

-

Panda or dragon? China’s strategy amid UN sanctions on Iran

-

The strategic loom: Weaving Saudi Arabia into a U.S.-Israel framework

-

Implementation begins for Iran’s new law supporting citizens abroad

-

Iran expands economic ties with Afghanistan with new trade, mining, energy initiatives

-

MAGA is dead. Israel did it.

-

Washington pressuring Lebanon’s president and army

-

Tehran, Beijing outline housing cooperation roadmap ahead of planned MOU

-

International law has collapsed under great-power pressure, UN observer warns

-

Tehran dispatches first Sunni ambassador under President Pezeshkian's administration for Bangladesh

-

Tehran condemns UN Gaza resolution over violation of Palestinian rights

-

Iran, Jordan warn Gaza crisis deepening as Israel continues ceasefire violations

-

Mazandaran hosts Caspian tour operators and influencers to promote Iran’s image

-

Will MBS become ambassador of peace between Iran and US?

-

Iran’s performance in Al Ain raises broader concerns