-

2025-12-05 21:36

2025-12-05 21:36

By Soheila Zarfam

Sahand 2025 showcases Iran's role as hub for counter-terrorism cooperation

Drill comes despite Western attempts at stigmatizing IRGC

TEHRAN – The Islamic Revolution Guard Corps (IRGC) Ground Force concluded its hosting of a five-day multinational military exercise on Iranian soil, with drills that not only sent a message to terrorist factions in the region but also delivered a political message to Western states seeking to isolate and stigmatize the unit.

-

By Sahar Dadjoo

Iran’s steadfast stance has transformed resistance politics in West Asia: Malaysian activist

Mohd Azmi Abdul Hamid says Iran’s resistance to Western pressure gives it unique strategic weight

TEHRAN – At the sidelines of the Conference on “People’s Rights and Legitimate Freedoms in the Thoughts of Ayatollah Khamenei,” The Tehran Times sat down with Mohd Azmi Abdul Hamid, President of the Malaysian Consultative Council of Islamic Organizations (MAPIM), to discuss the evolving landscape of global justice, Palestine advocacy, and the role of the Muslim world in confronting oppressive power structures.

-

By Shahrokh Saei

Professor Azarov argues the West moves Ukraine like a pawn in a grand game

TEHRAN – The war in Ukraine has emerged as one of the defining struggles of the 21st century, redrawing global fault lines and igniting fierce debate over its origins. While the result of US-mediated talks over the war between Russia and Ukraine remains unclear, the question of how this confrontation began — and why it has endured — has taken on fresh urgency.

-

By Lucia Hubinská

Is Japan sliding back toward militarism?

XIAMEN – Relations between China and Japan are undergoing their most serious shock in a decade. And yet, as recently as 2024—after the lifting of pandemic restrictions—it seemed the two countries were slowly moving toward improved relations. This trend was abruptly disrupted in recent weeks, when a series of diplomatic missteps gave way to open disputes.

-

By Sondoss Al Asaad

Lebanon’s art of giving everything away for free

BEIRUT — For decades, Lebanon’s leaders have embraced a peculiar diplomatic approach: yield concession after concession, gain nothing in return, and feign surprise as the nation’s leverage steadily disappears.

-

By Wesam Bahrani

Israel utterly failed to shield its protégé in Gaza

TEHRAN – The occupying Israeli regime suffered a setback after its most prominent militia leader was killed in Gaza.

Politics

-

‘Political statements won’t change reality’: Tehran denounces PGCC remarks on Iranian territories

TEHRAN – Iran’s Foreign Ministry Spokesman Esmail Baqaei has strongly rejected as “unfounded and invalid” allegations in the final statement of the 46th summit of the Persian Gulf Cooperation Council (PGCC) regarding the three Iranian Persian Gulf Islands of the Greater and Lesser Tunbs as well as Bu Musa.

-

Iran stages second major naval drill since war with Israel

TEHRAN – The Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC) Navy has launched a large-scale military exercise in the Persian Gulf, unveiling advanced AI-enhanced defensive and offensive systems in what marks the country’s second major naval drill since it fought a war against the U.S. and Israel in June.

-

Public back-and-forth continues between Araghchi and Lebanese counterpart

TEHRAN – Tehran moved to calm diplomatic waters on Thursday after Iran’s Foreign Minister, Abbas Araghchi, firmly reiterated the Islamic Republic’s unwavering respect for Lebanese sovereignty, following what appeared to be an excessive and unexpected reaction from Lebanon’s top diplomat to an Iranian politician’s warning about the whittling away of Lebanon’s defense prowess in the face of continued Israeli aggression.

Sports

-

Iran aims to defend title at 2025 Asian Youth Para Games: chef de mission

TEHRAN – Maryam Kazemipour, chef de mission of Iran’s delegation, says the team is determined to defend its title at the 2025 Asian Youth Para Games.

-

Iran to meet Belgium, Egypt and New Zealand: 2026 FIFA World Cup

TEHRAN – Iran national football team discovered their opponents at the 2026 FIFA World Cup.

-

Iranian taekwondo athletes win two more golds at 2025 World U21

TEHRAN – Iran’s Mobina Nematzadeh and Radin Zeinali won two gold medal at the 2025 World U21 Taekwondo Championships on Friday.

Culture

-

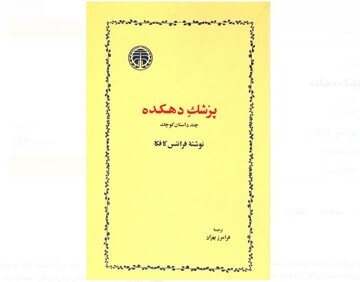

Persian version of “A Country Doctor” republished

TEHRAN- The fifth edition of a Persian translation of the Czech writer Franz Kafka’s 1919 short story collection “A Country Doctor” has recently been released by the Kharazmi Publications in Tehran.

-

What’s in Tehran art galleries

Sharif Gallery is playing host to an exhibition of paintings by Hanieh Azmoodeh. The exhibit entitled “Moment” will be running until December 19 at the gallery that can be found at 11 Mahruzadeh Alley, Shariati Ave. near Quds Square.

-

43rd Fajr International Film Festival concludes in Shiraz

TEHRAN-The 43rd Fajr International Film Festival (FIFF) concluded on Tuesday night, with an awards ceremony held at the Honar Shahr Aftab Cineplex in Shiraz, Fars Province.

Economy

-

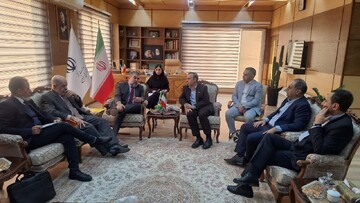

Tehran, Yerevan discuss ways to expand economic, trade, investment co-op

TEHRAN- During a meeting between the ambassador of Armenia to Iran and the secretary of Iran’s Supreme Council of Free Trade and Special Economic Zones, they discussed ways to develop bilateral cooperation and strengthen economic, trade, and investment relations between the two countries.

-

Economic cooperation in focus as Brazilian ambassador meets Qazvin governor

TEHRAN – Brazil’s Ambassador to Iran, André Veras Guimarães, met with Mohammad Nozari, the governor of Qazvin Province, on Wednesday.

-

Chinese private sector shows growing interest in entering Iran’s market

TEHRAN – Iran’s Industrial Development and Renovation Organization (IDRO) has said is prepared to expand joint investments with Chinese companies in renewable energy, electric vehicles and rail industries, noting that Chinese private sector has shown growing interest in entering Iranian market, the head of the organization said during a meeting with Iran’s ambassador to China.

Society

-

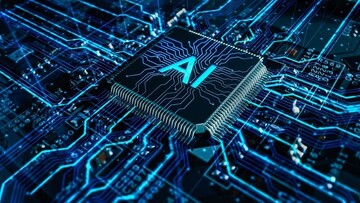

Science ministry finalizes AI action plan

TEHRAN – The Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology has announced the finalization of an artificial intelligence (AI) action plan, which highlights the pivotal role of AI in the country’s scientific advancement.

-

IUCN classifies Persian Gulf mangroves as ‘vulnerable’

TEHRAN – The first global assessment of mangroves by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has classified mangrove forests in the Persian Gulf as vulnerable (VU) overall.

-

Tehran, Kabul discuss boosting health cooperation

TEHRAN – Iranian and Afghan officials have discussed ways to promote cooperation between the two countries in the pharmaceutical and medical equipment fields.

Tourism

-

A thousand stories under one name, Herbert Karim-Masihi reflects on his new exhibition

TEHRAN – Iranian-Armenian photographer, and cultural heritage researcher Herbert Karim-Masihi is presenting a new exhibition titled “Iran Thinks of You” at the Sa’dabad Cultural-Historical Complex in northern Tehran.

-

‘The Land of Legends’ unveiled at National Museum ceremony

TEHRAN – The unveiling ceremony of the book “Iran, The Land of Legends” was held on Tuesday evening at the National Museum.

-

First ‘Kerman to Rayen’ tourist train departs

TEHRAN--The first tourist train departed from Kerman station to Rayen on Thursday. An action that marks the beginning of a new chapter in the development of travel infrastructure, strengthening the sustainable tourism, and creating new experiences for tourists in the southeast of the country.

International

-

Is Japan sliding back toward militarism?

XIAMEN – Relations between China and Japan are undergoing their most serious shock in a decade. And yet, as recently as 2024—after the lifting of pandemic restrictions—it seemed the two countries were slowly moving toward improved relations. This trend was abruptly disrupted in recent weeks, when a series of diplomatic missteps gave way to open disputes.

-

Lebanon’s art of giving everything away for free

BEIRUT — For decades, Lebanon’s leaders have embraced a peculiar diplomatic approach: yield concession after concession, gain nothing in return, and feign surprise as the nation’s leverage steadily disappears.

-

Israel utterly failed to shield its protégé in Gaza

TEHRAN – The occupying Israeli regime suffered a setback after its most prominent militia leader was killed in Gaza.

Video Comment

-

Ayatollah Khamenei’s vision of freedom and humanity discussed in intl. conference

-

Iran hosts SCO joint anti-terror drills

-

Holy Mary Metro Station marks interfaith unity in Tehran

-

Academics analyze social dimensions of Resistance in Tehran conference

-

Culture minister highlights year of progress in arts, global image enhancement

Most Viewed

-

Iran to meet Belgium, Egypt and New Zealand: 2026 FIFA World Cup

-

A thousand stories under one name, Herbert Karim-Masihi reflects on his new exhibition

-

Sahand 2025 showcases Iran's role as hub for counter-terrorism cooperation

-

Iran stages second major naval drill since war with Israel

-

Is Japan sliding back toward militarism?

-

Israel utterly failed to shield its protégé in Gaza

-

Lebanon’s art of giving everything away for free

-

Tehran, Yerevan discuss ways to expand economic, trade, investment co-op

-

Palestinians celebrate as young couples attend mass wedding

-

Science ministry finalizes AI action plan

-

Iran hosts SCO joint anti-terror drills

-

Iran’s steadfast stance has transformed resistance politics in West Asia: Malaysian activist

-

Professor Azarov argues the West moves Ukraine like a pawn in a grand game

-

Chinese private sector shows growing interest in entering Iran’s market

-

Iran fall short to Croatia at 2025 President’s Cup