-

2026-01-31 21:24

2026-01-31 21:24

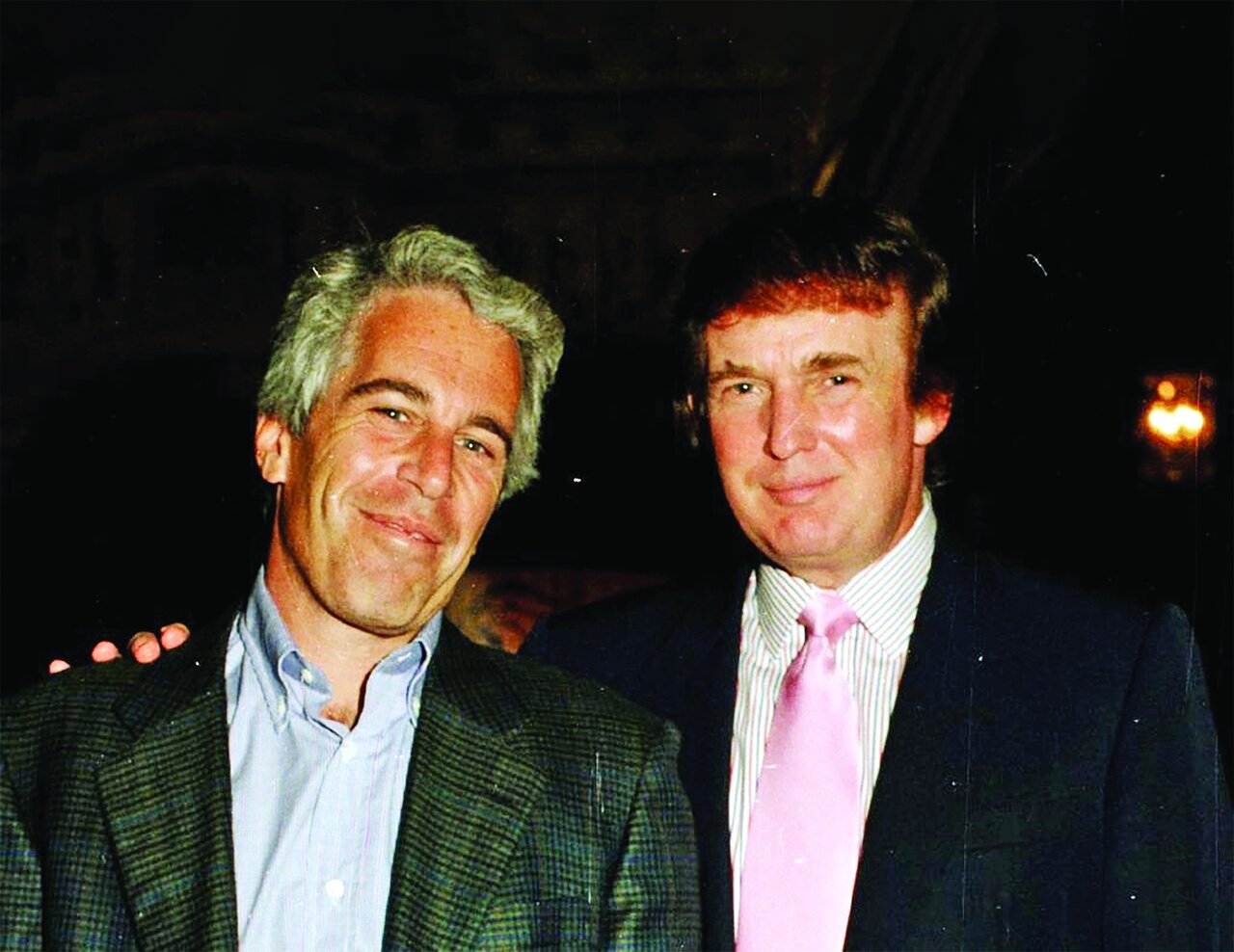

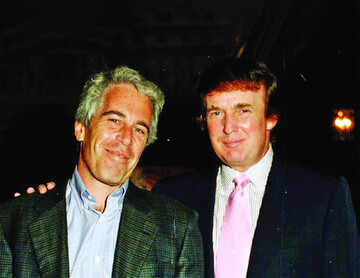

Trump’s tower of deceit: Epstein’s files pull back the curtain

Over three million pages of DOJ files fuel critical allegations, placing the U.S. president at the heart of Epstein's elite sex scandal network

TEHRAN – The newest release of the Epstein files has once again pulled U.S. President Donald Trump, along with a long list of powerful figures, into the center of a story that refuses to fade. The U.S. Department of Justice — the federal agency responsible for enforcing the law and overseeing the FBI — published more than three million pages of documents, along with thousands of images and videos, on Friday. What emerged is a portrait of Epstein’s world that is both familiar and newly disturbing: a network of wealth, secrecy, and influence that stretched across politics, entertainment, business, and even intelligence circles.

-

By Abbas Akhoundi

A framework for collective security in the Persian Gulf and West Asia

TEHRAN - The gradual erosion of the liberal international order and the emergence of a more coercive global environment have profoundly altered the security calculus for middle powers. In the current international landscape—often described as a “new world order”—the direct use of force by major powers has become increasingly normalized.

-

By Fatemeh Kavand

American security and double standard of disorder

TEHRAN - While Donald Trump labels American protesters “professional agitators” and calls for their imprisonment or deportation, the very same pattern of behavior has for years been framed in Western narratives of insecurity in Iran as “civil protest”—a stark rupture in how order, security, and the legitimacy of violence are defined.

-

Putin hosts Iranian security chief in Kremlin

TEHRAN — President Vladimir Putin received Ali Larijani, the Secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, for a high-stakes summit at the Kremlin on Friday.

-

By Sondoss Al Asaad

How is Washington’s oil-first strategy redrawing Libya’s geopolitical map?

BEIRUT — The recent visits of Massad Boulos, adviser to U.S. President Donald Trump for the Middle East and African affairs, to Tripoli and Benghazi have ignited intense debate inside Libya.

-

Araghchi to Washington: Diplomacy is not a one-way street of dictates

Iranian FM says ‘U.S. must give assurances there will be no new attack or threat’

TEHRAN — Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi has delivered a sharp message to Washington and its European allies, asserting that while Iran remains open to “fair and balanced” diplomacy, it will never negotiate under the shadow of threats or accept dictates from foreign powers.

Politics

-

Egypt urges de-escalation in calls with Iran and US

TEHRAN — Egypt has intensified diplomatic efforts to prevent renewed conflict in West Asia, holding separate phone calls with Iran’s foreign minister and the U.S. Middle East envoy amid mounting regional concern that President Donald Trump’s escalating rhetoric could push the region toward another war.

-

Government must listen to the grievances of people: Pezeshkian

TEHRAN - President Masoud Pezeshkian said on Saturday that officials must listen to the grievances of the people.

-

Army chief says ‘Iran’s finger on the trigger’ as US talks up naval military buildup

TEHRAN – The commander-in-chief of Iran’s Army (Artesh) has reaffirmed that the country’s armed forces are on full combat alert, warning that any reckless move by the United States or Israel would backfire catastrophically, threatening not only their own forces but the entire region.

Sports

-

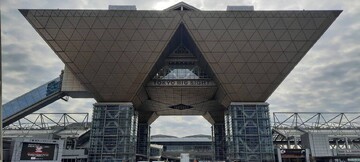

Our main goal is gold at 2026 Asian Para Games: Behrouz Soltani

TEHRAN – Behrouz Soltani, head coach of Iran’s national wheelchair basketball team, said that their primary objective is to win the gold medal at the 2026 Asian Para Games in Nagoya.

-

We need to criticize ourselves to fix weaknesses: Jafari

TEHRAN – Marzieh Jafari, head coach of Iran’s women’s national football team, says self-criticism is essential as the team prepare for the 2026 AFC Women’s Asian Cup.

-

Iran’s Gorgan lose to Astana: 2025/26 FIBA WASL

TEHRAN - BC Astana rose to solo no. 2 in the 2025/26 FIBA WASL-West Asia League standings following a vengeful 88-73 victory over Shahrdari Gorgan at the Sarkarya Velodrome on Friday night.

Culture

-

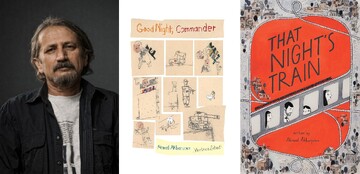

Iranian children’s author Ahmad Akbarpour nominated for 2026 Hans Christian Andersen Awards

TEHRAN – The International Board on Books for Young People has announced the shortlist for the 2026 Hans Christian Andersen Awards, with an Iranian author in the list.

-

16th Ammar Popular Film Festival concludes in Tehran

TEHRAN – The 16th Ammar Popular Film Festival concluded on the evening of Thursday, January 29, in Tehran.

-

Iranian artist pens truth on Venezuela's front page

TEHRAN- An Iranian artist has articulated the nation's perspective on recent developments through the platform of a major Venezuelan publication.

Economy

-

World Bank says 3 governance indicators improved in Iran

TEHRAN – The World Bank said three of Iran’s governance indicators improved in 2024, citing gains in government effectiveness, control of corruption and accountability.

-

IMIDRO says 420 exploration maps to draw private investment

TEHRAN – Iran’s Mines and Mining Industries Development and Renovation Organization (IMIDRO) plans to use more than 400 newly produced exploration maps to attract private sector participation and reduce risk in mineral exploration, its head said.

-

Paknejad plays down concerns over U.S. dealings with Iran’s oil customers

TEHRAN – Iran’s oil minister dismissed concerns that potential U.S. dealings with buyers of Iranian crude could undermine Tehran’s oil sales or revenues, saying the country remains in control of its export strategy.

Society

-

DOE underscores use of smart environmental protection systems

TEHRAN – Given that traditional methods can no longer meet the needs of a fragile environment, the integration of smart technologies for environmental conservation seems inevitable, an official with the Department of Environment has said.

-

Iran to host ANF specialized standardization workshop

TEHRAN – Iran will play host to a specialized standardization workshop for the member states of the Asian Network Forum (ANF) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Technical Committee (TC) 229.

-

Third national event on ‘future schools’ to be held

TEHRAN – The third national event on future schools will be held in February, highlighting the use of modern technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and blended learning in fostering thinking skills and creativity, as well as collaboration among the future generation of students.

Tourism

-

Koozeh-Shekani: Where tradition, belief and renewal converge

TEHRAN - The Koozeh-Shekani ceremony is one of the nearly forgotten traditions observed on the eve of the last Wednesday of the Iranian calendar year, coinciding with Charshanbe Suri, in some villages and towns of South Khorasan province in eastern Iran.

-

Natural heritage overlooked in Iran’s tourism policy, researcher says

TEHRAN – Iran’s natural heritage is an integral part of the country’s national identity but remains poorly defined, under-prioritized and constrained by institutional conflicts, a natural heritage expert said.

-

Ancient Sadeh festival can reinforce social cohesion and unity, governor-general says

TEHRAN – Kerman’s governor-general Mohammad-Ali Talebi said on Wednesday that the ancient Sadeh festival is a national ritual belonging to all Iranians and can contribute to social cohesion and unity.

International

-

Trump’s tower of deceit: Epstein’s files pull back the curtain

TEHRAN – The newest release of the Epstein files has once again pulled U.S. President Donald Trump, along with a long list of powerful figures, into the center of a story that refuses to fade. The U.S. Department of Justice — the federal agency responsible for enforcing the law and overseeing the FBI — published more than three million pages of documents, along with thousands of images and videos, on Friday. What emerged is a portrait of Epstein’s world that is both familiar and newly disturbing: a network of wealth, secrecy, and influence that stretched across politics, entertainment, business, and even intelligence circles.

-

How is Washington’s oil-first strategy redrawing Libya’s geopolitical map?

BEIRUT — The recent visits of Massad Boulos, adviser to U.S. President Donald Trump for the Middle East and African affairs, to Tripoli and Benghazi have ignited intense debate inside Libya.

-

Rafah border crossing: What the reopening reveals about Israel’s next moves

TEHRAN – The scheduled opening of the Rafah border crossing on Sunday is another sign of the Israeli regime’s larger scheme.

Most Viewed

-

‘Iran as ready for diplomacy as it is for war’

-

Iran Army bolsters combat power with massive drone integration

-

U.S. seeks an Iran that is subservient, says Chinese expert

-

Trump’s threats against Iraq could backfire

-

Iran’s response to any aggression will be ‘immediate, decisive:’ Pezeshkian warns

-

Tehran warns Berlin of consequences following Merz’s ‘low-minded provocations’

-

Iran to EU: IRGC is world’s premier anti-terror vanguard

-

US officials' disagreement over military attack on Iran

-

Israel’s admission of Gaza death toll shatters its own denial

-

New Iranian vessel to be unveiled in Caspian Sea, co-op with Russia planned in 200 petchem projects

-

Qalibaf says Iran will pursue justice for terror riot victims at home and abroad

-

Iran’s non-oil trade tops $94b in 10 months

-

What was used by terrorists to kill innocent people?

-

Iran defeat Saudi Arabia in 2026 AFC Futsal Asian Cup

-

Iran, China and Russia to hold naval drill