-

2025-09-10 03:58

2025-09-10 03:58

By Shahrokh Saei

Trump’s trap: Fueling Israel’s Qatar attack and advancing 'Greater Israel' vision

TEHRAN – International condemnation is mounting following a deadly Israeli airstrike on a residential area in Qatar’s capital, Doha.

-

Iran decides to resume cooperation with IAEA

TEHRAN – Iran has decided to look for ways to allow International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspectors back into the country, after it suspended cooperation with the UN nuclear watchdog back in July following U.S.-Israeli attacks on its nuclear sites.

-

By Soheila Zarfam

Your statements are good, but not enough

Pezeshkian tells Arab states to do something about Israel’s growing aggression after two years of inaction

TEHRAN – Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian spent much of his time at a conference marking the Islamic Unity Week in Tehran making general remarks about how unity among Muslims is important, and how cohesion will benefit all Muslim nations in the region. At one point though, he took a more firm and straightforward tone, asking regional states to do more than condemnation in addressing Israel’s unchecked violence in the region.

-

The role of Muslim leaders in strengthening the BRICS coalition

TEHRAN – The convening of the “Second Meeting of Muslim Leaders of BRICS Countries” hosted by Brazil is a turning point in the life of this forum and, beyond that, a pillar in strengthening the BRICS coalition. The consultation and synergy of Muslim leaders within the BRICS framework regarding international crises is not merely desirable, but an absolute necessity.

-

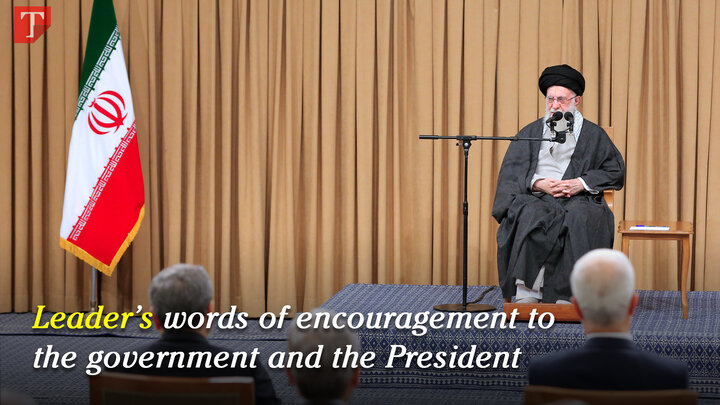

Leader welcomes Pezeshkian's visit to China:

Potentials for economic and political cooperation with China must be pursued

TEHRAN – Leader of the Islamic Revolution Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Khamenei told the Pezeshkian administration on Sunday that the government should not let the threat of a potential war with Israel or the United States derail its ongoing plans and their implementation.

-

By Mohammad Khatibi

Strait of Hormuz, China’s imperative for deeper engagement in Persian Gulf

TEHRAN – Beijing’s growing dependence on Persian Gulf oil and its aspiration to play mediator in the West Asia disputes collide in the narrow waters of the Strait of Hormuz. As more than 40% of China’s crude shipments flow through this chokepoint, how China maneuvers its ambitions without sparking a direct clash has become a vital barometer of its evolving global role.

Politics

-

We won’t negotiate our missiles: Iran foreign ministry

TEHRAN – Iran has reaffirmed that its missile and defense capabilities are not subject to negotiation, even as it continues diplomatic engagement with Europe and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) amid heightened tensions over sanctions and nuclear safeguards.

-

The role of Muslim leaders in strengthening the BRICS coalition

TEHRAN – The convening of the “Second Meeting of Muslim Leaders of BRICS Countries” hosted by Brazil is a turning point in the life of this forum and, beyond that, a pillar in strengthening the BRICS coalition. The consultation and synergy of Muslim leaders within the BRICS framework regarding international crises is not merely desirable, but an absolute necessity.

-

Iran unveils multiple satellite launch plans amid push for space self-reliance

TEHRAN – Iran has unveiled plans for a series of satellite launches in the second half of the current year, underscoring its determination to expand its domestic space program and reduce reliance on foreign technology.

Sports

-

Iran advance to AFC U23 Asian Cup Saudi Arabia 2026

TEHRAN – Iran held off a fightback from the United Arab Emirates to top Group I of the AFC U23 Asian Cup Saudi Arabia 2026 Qualifiers Group I with a 3-2 win on Tuesday.

-

Infantino assures Iran for 2026 World Cup’s participation

TEHRAN – FIFA President Infantino assured the team members of Iran national football team that FIFA will do its utmost to resolve visa-related issues and facilitate the teams’ participation in upcoming tournaments, including the 2026 World Cup.

-

10-man Iran runners-up at 2025 CAFA Nations Cup

TEHRAN – Iran conceded a late goal to Uzbekistan in the final match of the 2025 CAFA Nations Cup on Monday.

Culture

-

Short documentary “Karun – The Longest River of Iran” wins at Armenian festival

TEHRAN – The Iranian short documentary “Karun – The Longest River of Iran” written and directed by Sahand Sarhaddi won an award at the 11th Apricot Tree International Documentary Film Festival, which was held from August 30 to September 6 in Yerevan, Armenia.

-

Tehran meeting to mark Jalal Al-e Ahmad’s legacy, social impact

TEHRAN- A literary forum titled "Jalal, Literature, and Social Engagement" is scheduled to be held at the Amir Kabir Publications Bookstore on Tuesday.

-

Arasbaran Cultural Center reviews “The Life of Chuck”

TEHRAN- “The Life of Chuck”, a 2024 fantasy movie by American filmmaker Mike Flanagan, went on screen at the Arasbaran Cultural Center in Tehran on Sunday.

Economy

-

Tehran, Ashgabat push to boost rail transit, target 20m tons

TEHRAN – Iran and Turkmenistan agreed to draw up a joint action plan to expand rail cooperation and raise annual transit volumes to 20 million tons, including 6.0 million tons by rail, during talks between their transport ministers in Tehran on Sunday.

-

Russia energy officials to visit Tehran for gas export deal talks: envoy

TEHRAN – Iran’s ambassador to Moscow said senior officials from Russia’s Energy Ministry will soon travel to Tehran on President Vladimir Putin’s orders to finalize a gas export agreement.

-

Iran Plast 2025 intl. exhibition opens in Tehran

TEHRAN – The 19th International Exhibition of Plastic, Rubber, Machinery, and Equipment (IRAN PLAST 2025) opened on Monday with the participation of senior Oil Ministry officials, petrochemical executives and industry representatives at Tehran’s Permanent International Fairgrounds.

Society

-

GII 2025 places Tehran 63rd among top 100 science and technology clusters

TEHRAN – The Global Innovation Index (GII) has ranked Tehran as the world’s 63rd-largest science and technology (S&T) cluster this year, according to a report released by the UN’s World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).

-

Tehran, Yerevan sign MOU on science

TEHRAN – Science Minister Hossein Simaei-Sarraf and his Armenian counterpart, Zhanna Andreasyan, signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) here on Monday to expand scientific cooperation between the two countries.

-

Iran is a successful model of scientific, technological development: COMSTECH general coordinator

TEHRAN –Muhammad Iqbal Chaudhry, the coordinator general of the Standing Committee for Scientific and Technological Cooperation of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (COMSTECH), has highlighted Iran’s capacity in innovation and technology as one of the most successful countries in the world.

Tourism

-

Sistan-Baluchestan: land of flavors, music, and living traditions

TEHRAN - Sistan-Baluchestan is more than just a geographical region on Iran’s map. It is a land of colors, music, flavors, and traditions, where a rich culture and history meet in everyday life.

-

Iran to showcase traditional arts at Bangkok diplomatic fair in November

TEHRAN - Iran will present traditional handicrafts and arts at the 70th YWCA Diplomatic Charity Bazaar in Bangkok from Nov. 6 to 9, the country’s cultural office in Thailand has said.

-

Archaeologist rejects claim of discovery of Seljuk palace in Kamar-Zarrin passage

TEHRAN—Prominent archaeologist Alireza Jafari-Zand emphasized that there is no sign of a Seljuk palace in Kamar-Zarrin site in Isfahan, and the published news lacks a scientific basis and is propaganda.

International

-

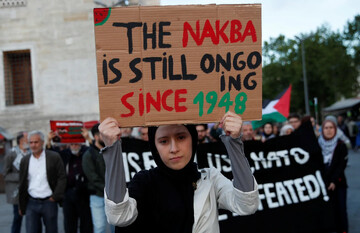

Zionism is the problem: Ariel Feldman breaks down Israel’s Nakba and genocide

BUENOS AIRES — Ariel Feldman is an audiovisual filmmaker, lecturer in film and philosophy, and photographer who supports Palestine and denounces Israel’s colonial and genocidal policies. Drawing from his life experience in Israel and his Jewish identity, Feldman calls for ethical awareness in the face of the Israeli occupation and the suffering of the Palestinian people.

-

How has the Lebanese Army saved Lebanon at a crucial moment?

BEIRUT — What happened in the Lebanese government session on Friday was a truce that could either be sustained or overturned. The Lebanese Army did not rebel against the political authority, but rather put an end to the abuse of political establishment in a bloody, destructive conflict.

-

Israeli tanks explode in Gaza

TEHRAN – The Palestinian resistance in Gaza wages more deadly operations against the Israeli Occupation Forces (IOF) attempting to invade Gaza City.

Video Comment

-

Culture minister highlights year of progress in arts, global image enhancement

-

Gazan Journalists attacked by Israel

-

Brother of Iranian scientist murdered in Israeli strike speaks out

-

Footage shows Israel hit a kindergarten in Tehran

-

Delegates and ambassadors from 28 countries visited the IRIB building

Most Viewed

-

Iran decides to resume cooperation with IAEA

-

Yemen announces second day of strikes on Israeli targets

-

10-man Iran runners-up at 2025 CAFA Nations Cup

-

Tehran, Ashgabat push to boost rail transit, target 20m tons

-

Your statements are good, but not enough

-

Turning opportunities into action: Iran-China partnership through the lens of GGI framework

-

Iran unveils multiple satellite launch plans amid push for space self-reliance

-

Russia energy officials to visit Tehran for gas export deal talks: envoy

-

We won’t negotiate our missiles: Iran foreign ministry

-

Exclusive: UN risks irrelevance if Gaza genocide ignored, warns Alfred de Zayas

-

Trump’s trap: Fueling Israel’s Qatar attack and advancing 'Greater Israel' vision

-

Strait of Hormuz, China’s imperative for deeper engagement in Persian Gulf

-

Iran, Iraq sign 21-point cooperation agreement covering economy, security, and politics

-

The role of Muslim leaders in strengthening the BRICS coalition

-

Sistan-Baluchestan: land of flavors, music, and living traditions