-

2026-02-02 22:23

2026-02-02 22:23

By Faramarz Kouhpayeh

Killing with sanctions, lying with statistics

Iran releases names of 3000 killed in January unrest after days of fabricated and politically motivated reporting by Western media

TEHRAN – On Sunday, Iran took the step of publishing the names and national ID numbers of nearly 3,000 individuals killed during the unrest that swept through the country between January 8 and January 14. According to officials, this move was a direct response to weeks of politically motivated reporting and fabrication by Western media outlets.

-

Group painting exhibition “Timeless Love” opens on birth anniversary of Imam Mahdi (AS)

TEHRAN – Coinciding with the birth anniversary of Imam Mahdi (AS), Akhlagh Cultural Center in Tehran is hosting the group painting exhibition “Timeless Love”.

-

By Fatemeh Kavand

‘American rescue’: A mask of compassion, a face of plunder

TEHRAN - While the Trump administration is officially considering regime-change options in Cuba, reviewing the experiences of countries previously targeted for “American rescue” shows that this concept is not about the welfare of nations—it is a cover for blockade, pressure, and systematic plunder. This pattern also explains Washington’s hostility toward Iran.

-

AI-generated fake accounts linked to Israel wage digital war on Iran: Le Figaro

TEHRAN – French newspaper Le Figaro has reported that researchers and disinformation specialists have observed an increase in coordinated campaigns targeting the Iranian public.

-

Pompeo boasts of ‘lots of help’ provided to Iran’s deadly riots

TEHRAN — Mike Pompeo, the former U.S. Secretary of State and CIA director, has provided a rare public admission that Washington orchestrated the recent wave of deadly unrest and terror attacks across the Islamic Republic.

-

Iran poised for nuclear talks resumption with US, reports say

TEHRAN — Negotiating teams from the Islamic Republic of Iran and the United States are reportedly poised to resume high-level discussions in the coming days, with diplomatic momentum building toward a potential meeting in Istanbul as early as Friday.

Politics

-

Iranians won’t succumb to psychological warfare: 2600 Iranian psychologists tell US

TEHRAN - Some 2600 psychologists and advisors from various Iranian universities have signed a statement in reaction to Washington’s repeated military threats against Iran and efforts to inject psychological instability into the Iranian society.

-

Instigators of insecurity and terrorists will face justice: Iranian top judge

TEHRAN - The Iranian Judiciary chief says the judicial system will firmly deal with those instigating insecurity and conducting acts of terror and treason.

-

‘Iran ready to respond to any mischief by enemy’

TEHRAN - An Iranian parliamentarian has quoted a senior military commander as saying the Islamic Republic is prepared to respond to any mischievous move by the enemy.

Sports

-

Iran’s relentless march toward another Asian futsal crown

TEHRAN - Iran’s national futsal team once again find themselves exactly where they expect to be: deep in the business end of the AFC Futsal Asian Cup.

-

Female sprinter Fasihi wins gold at Budapest event

TEHRAN – Farzaneh Fasihi of Iran won a gold medal at the Budapest Régió Fedettpályás Bajnokság.

-

Iran see off Uzbekistan in AFC Futsal Asian Cup 2026 QFs

TEHRAN - Iran came from two goals down to defeat Uzbekistan 7-4 in a thrilling AFC Futsal Asian Cup Indonesia 2026 quarter-final on Tuesday.

Culture

-

Group painting exhibition “Timeless Love” opens on birth anniversary of Imam Mahdi (AS)

TEHRAN – Coinciding with the birth anniversary of Imam Mahdi (AS), Akhlagh Cultural Center in Tehran is hosting the group painting exhibition “Timeless Love”.

-

“Shadow of Security” unveiled at Art Bureau

TEHRAN- The unveiling ceremony for “Shadow of Security,” a painting by Iranian artist Hassan Ruholamin, was held at the Art Bureau of the Islamic Ideology Dissemination Organization in Tehran on Tuesday.

-

Karaj theater to host reading performance of “Twelve Angry Men”

TEHRAN- Master Sirous Saber Theater in Karaj will be playing host to a reading performance of American screenwriter and playwright Reginald Rose’s “Twelve Angry Men” on Friday.

Economy

-

Car output down 7% in nine months

TEHRAN – Iran’s car production fell seven percent in the first nine months of the current Iranian year (March 21-December 21, 2025) compared with the same period last year, the head of the Industrial Development and Renovation Organization of Iran (IDRO) said.

-

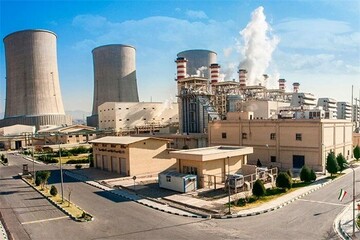

Power projects worth $1.1b to be inaugurated across Iran

TEHRAN – Energy Ministry will inaugurate 243 power sector projects nationwide during the Ten-Day Dawn anniversary period, with total investment of about 550 trillion rials ($1.1 billion), a senior official at Iran's Power Generation, Distribution, and Transmission Company (Tavanir) said.

-

Iran ranks among top 10 countries by thermal power capacity

TEHRAN – Iran ranks among the world’s 10 countries with the largest thermal power generation capacity, a senior official at the Thermal Power Plants Holding Company (TPPH) said.

Society

-

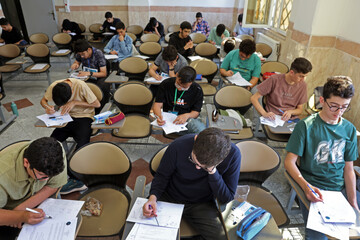

Iran among top eight countries in intl. Olympiads

TEHRAN –Iran ranks eight worldwide in international Olympiads as the country stood respectively third, seventh, and eighth in mathematics, computer, and physics Olympiads last year, IRNA quoted Reza Hosseini, the head of the Young Scholars Club, as saying.

-

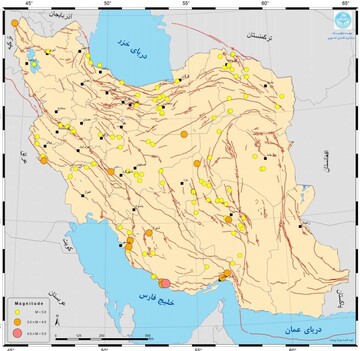

122 earthquakes hit Iran in a week

TEHRAN – A total of 122 earthquakes were recorded across the country in a week from January 24 to 30, according to the seismological networks of the Institute of Geophysics of the University of Tehran.

-

DOE holds conference on Intl. Wetlands Day

TEHRAN – The Department of Environment (DOE) organized a conference in Tehran on Monday to mark International Wetlands Day, with representatives from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and the embassies of the UAE, Iraq, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan in attendance.

Tourism

-

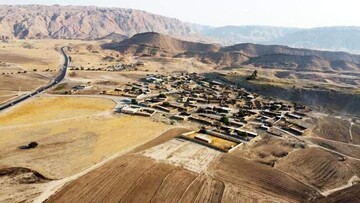

Legal protection boundaries determined for Batvand site

TEHRAN – Cultural heritage authorities have designated legal boundaries and a protected zone for the historical site of Batvand in Khuzestan province, officials said, in a move aimed at strengthening preservation measures.

-

Flamingos migrate to Makran coast, official says, highlighting tourism potential

TEHRAN – More than 2,000 flamingos have migrated to Makran coasts in southern Iran this winter that could support nature-based tourism, an environmental official has said.

-

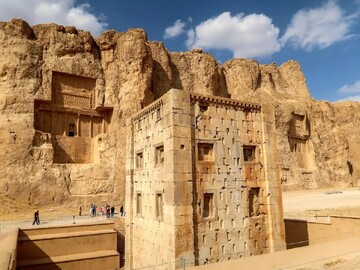

Work on Xerxes I tomb at Naqsh-e Rostam nears completion

TEHRAN – Restoration work on the rock-cut tomb of Achaemenid king Xerxes I is nearing completion after years of conservation efforts, a local official has said.

International

-

Israel kills 18 Palestinians in Gaza bombing

TEHRAN- Israeli fighter jets bombed the Gaza Strip early on Wednesday, killing at least 18 Palestinians, including three children, according to local media.

-

UN chief urges Gaza aid as Israel blocks most medical evacuees at Rafah

TEHRAN- United Nations chief Antonio Guterres again has called on Israel to immediately allow humanitarian aid into the Gaza Strip, as the Israeli authorities continue to block dozens of Palestinians from exiting the war-ravaged enclave to seek medical treatment.

-

Trump’s call to ‘nationalize’ elections draws furious pushback

TEHRAN- President Donald Trump on Tuesday doubled down on his controversial suggestion that Republicans "nationalize" elections as he continued to make false claims of widespread voter fraud and refused to accept his 2020 defeat, ABC news reported.

Most Viewed

-

Killing with sanctions, lying with statistics

-

AI-generated fake accounts linked to Israel wage digital war on Iran: Le Figaro

-

Iran poised for nuclear talks resumption with US, reports say

-

Pompeo boasts of ‘lots of help’ provided to Iran’s deadly riots

-

Foreign ministry repeats warning that any attack on Iran would trigger massive war

-

Iran’s military chief warns of blitzkrieg offensive against US

-

‘American rescue’: A mask of compassion, a face of plunder

-

Iranians won’t succumb to psychological warfare: 2600 Iranian psychologists tell US

-

Trump is retreating — here is why: John Helmer on Washington’s Iran strategy

-

Iraq must shield itself against U.S. plots

-

Free zones launch, break ground on 221 projects during Ten-Day Dawn

-

Annual inflation hits 44.2% in year to late-January: CBI

-

Iran tourism maintains international appeal, expert says

-

The new exodus of Israelis: Decolonizing Palestine beyond territory

-

More than $40m in preferential loans allocated to upgrade rail fleet