-

2026-02-18 23:15

2026-02-18 23:15

Iran-Russia cooperation expanding in all fields, including energy: Russian minister

By Mona Hojat Ansari

TEHRAN – Iran and Russia have steadily deepened their ties over the past decade, driven by geographic proximity, overlapping regional interests, and a shared sense of pressure from Western policies that threaten their national security and economic stability.

-

'Iran, Russia pledge to move beyond understanding to implementation'

TEHRAN- Iranian Oil Minister Mohsen Paknejad stated that what was ultimately agreed upon in the 19th meeting of Iran-Russia Joint Economic Committee represents the achievement of moving from understanding to the implementation phase.

-

Iran’s ‘inherent right’ to peaceful use of nuclear energy is non-negotiable: Araghchi

TEHRAN - Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi reiterated on Tuesday that Iran as a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) will not forego its right to nuclear technology for peaceful purposes, saying Tehran will not compromise on this right.

-

By Wesam Bahrani

Will Netanyahu resume genocidal war on Gaza?

TEHRAN – The Gaza Strip does not appear to be on the brink of a full-scale genocidal war anytime soon.

-

By Sondoss Al Asaad

The IMF trap: Balancing Lebanon’s budget on the backs of the poor

BEIRUT — On Monday, the Lebanese government approved a rise in the value-added tax (VAT) from 11% to 12% and imposed an additional 320,000 Lebanese lira levy on every gasoline canister.

-

Iran, Russia set to start naval drills in the Sea of Oman

TEHRAN – Iran and Russia will begin a joint naval drill in the northern Indian Ocean and the Sea of Oman on Thursday.

Politics

-

MPs voice support for Leader’s remarks

TEHRAN - Members of the Iranian Parliament have, in a statement, expressed their backing for recent comments by Leader of the Islamic Revolution Ayatollah Ali Khamenei by reaffirming their obedience to his instructions.

-

Pezeshkian sends congratulatory message to Japanese PM on National Day

TEHRAN - Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian has sent a message to Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, expressing congratulations to Japan on National Day.

-

Turkey reiterates concerns over consequences of a US war against Iran

TEHRAN -Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has reiterated his concern that a new U.S. war against Iran would destabilize the region.

Sports

-

Iran to compete at 2026 Muhamet Malo

TEHRAN – Iran will send a skilled, credentialed roster of 12 athletes—three in men’s freestyle, nine in Greco-Roman—to the 2026 Muhamet Malo tournament in Tirana, Albania.

-

Ricardo Sa Pinto to remain Esteghlal coach

TEHRAN - Esteghlal football club have decided to continue their cooperation with Portuguese head coach Ricardo Sa Pinto despite recent speculation about his future.

-

Manolopoulos extends deal with Iran basketball until 2028

TEHRAN - Sotiris Manolopoulos has officially extended his contract with the Iran Basketball Federation through 2028, reinforcing a partnership that has steadily grown stronger over the past two years.

Culture

-

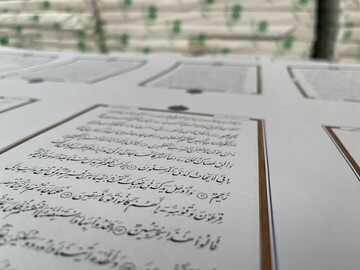

Exquisite handwritten Quran in Islamic world printed in Nastaliq script

TEHRAN – The first complete Holy Quran in Nastaliq script, following the style of Master Uthman Taha and approved by the Dar al-Quran Organization, has been published.

-

Russia’s cultural center inaugurated in Tehran

TEHRAN- The official inauguration ceremony of the Russia’s cultural center- Russian House- in Tehran was held on Tuesday morning, marking a new chapter in cultural diplomacy between the two countries.

-

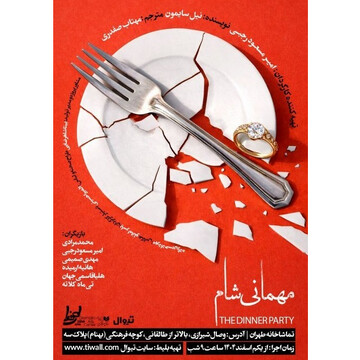

Neil Simon’s “The Dinner Party” to go on stage at Tehran Theater Complex

TEHRAN – The play “The Dinner Party,” a one-act comedy written by Neil Simon about marriage and divorce, will be performed at the Tehran Theater Complex from February 20.

Economy

-

Tehran, Dushanbe set $1b trade target, deepen industrial, mining ties

TEHRAN – Iran and Tajikistan have set a target of raising bilateral trade to $1.0 billion in the near future and agreed to expand joint investments and establish shared industrial plants, as senior officials from both sides moved to deepen economic and mining cooperation.

-

Over 100m tons of petroleum products transported annually

TEHRAN – More than 100 million tons of petroleum products are transported across Iran each year, accounting for around 17 percent of total freight movement in the country, a senior road transport official said.

-

Iran, Russia customs officials meet in Tehran to streamline trade procedures

TEHRAN – Customs delegations from Iran and Russia met in Tehran to expand training cooperation and facilitate customs clearance and supervision procedures, officials said.

Society

-

‘Russia interested in boosting scientific co-op with Iran’

TEHRAN – A Russian official has voiced his country’s interest in expanding scientific and academic ties with Iran to further technological cooperation between the two countries.

-

Knowledge-based firms to attend NextTech Week Tokyo

TEHRAN – An Iranian delegation of knowledge-based companies will participate in the NextTech Week exhibition, scheduled for April 15 to 17 at Tokyo Big Sight, Japan.

-

Iran ready to beef up tech ties with India in key sectors

TEHRAN – Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Minister Sattar Hashemi, in a meeting with Indian Minister of Electronics and Information Technology, Jitin Prasada, has voiced the country’s readiness for the expansion of scientific and technological ties with India in key sectors, particularly artificial intelligence (AI), cybersecurity, and digital economy.

Tourism

-

Khalid Nabi cemetery blends archaeology and pilgrimage

TEHRAN – Surrounded by vast skies, green hills in spring, and golden grasses in late summer, Khalid Nabi Cemetery stands as one of northern Iran’s most distinctive heritage destinations. It embodies a convergence of myth, memory, landscape, and identity—where pilgrimage, archaeology, and tourism meet on a remote mountain ridge overlooking Turkmen Sahra.

-

Iran plans maritime tourism line linking southern ports

TEHRAN – Iran’s Ports and Maritime Organization is planning to launch a maritime tourism line connecting the country’s southern ports, an official said on Thursday.

-

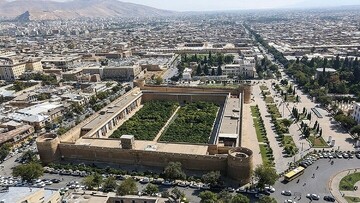

Shiraz historical fabric plan registered in national archives

TEHRAN - A plan outlining integrated regulations for the protection, management and development of the historical fabric of Shiraz has been officially registered by the National Library and Archives of Iran, authorities said.

International

-

Ramadan in Gaza: Palestinians' spirit unbroken despite all hardships

TEHRAN – Ramadan has arrived in Gaza, and as the first crescent moon appeared, people welcomed the holy month with the same devotion felt across the Muslim world. But in Gaza, Ramadan never comes quietly. It arrives under the long shadow of Israel’s occupation and the deep wounds left by years of blockade, bombardment, and displacement. It is a month of prayer and patience, but also a reminder of everything people have endured under Israeli control.

-

Will Netanyahu resume genocidal war on Gaza?

TEHRAN – The Gaza Strip does not appear to be on the brink of a full-scale genocidal war anytime soon.

-

The IMF trap: Balancing Lebanon’s budget on the backs of the poor

BEIRUT — On Monday, the Lebanese government approved a rise in the value-added tax (VAT) from 11% to 12% and imposed an additional 320,000 Lebanese lira levy on every gasoline canister.

Most Viewed

-

Iran, Russia set to start naval drills in the Sea of Oman

-

Pezeshkian sends congratulatory message to Japanese PM on National Day

-

Iran-Russia cooperation expanding in all fields, including energy: Russian minister

-

Iran’s ‘inherent right’ to peaceful use of nuclear energy is non-negotiable: Araghchi

-

'Iran, Russia pledge to move beyond understanding to implementation'

-

Turkey reiterates concerns over consequences of a US war against Iran

-

How faulty cognitive maps paralyze US strategy towards Iran

-

Iran invites UAE investors to tap major economic projects

-

MPs voice support for Leader’s remarks

-

Uruguay presents football shirts to Iran in gesture of sporting friendship

-

Will Netanyahu resume genocidal war on Gaza?

-

Ramadan in Gaza: Palestinians' spirit unbroken despite all hardships

-

In interview with Tehran Times, Russia reaffirms strategic energy ties with Iran

-

At least 10 foreign spy services fueled Iran’s January unrest, says intel. commander

-

The IMF trap: Balancing Lebanon’s budget on the backs of the poor