-

2025-12-13 21:13

2025-12-13 21:13

By Shahrokh Saei

Who benefits from a disarmed Lebanon?

TEHRAN – Lebanon’s fragile ceasefire with Israel, brokered in late November 2024 by the United States and France, was meant to halt hostilities and open the door to a negotiated settlement. Yet more than a year later, the truce has proven largely illusory. Israel continues near-daily strikes on Lebanese territory, claiming to target Hezbollah compounds and rocket launch sites, but offering no verifiable evidence to substantiate its assertions.

-

By Matin Jamshidi

Eurovision: A measure of international sentiment against Israel

TEHRAN - Israel may feel it has weakened Hamas and Hezbollah and now entertains the illusion that it is time to create a “new Middle East” and a “Greater Israel.” Yet these fleeting feelings of victory have come at the cost of unspeakable tragedy for civilians in Gaza.

-

Israel exploiting Syrian instability to expand territorial control, Lebanese analyst warns

Abir Bassam says Israel seeking to control all water sources in southern Syria and southern Lebanon

TEHRAN- As Syria marks one year since the fall of the Assad government, the country faces unprecedented political, social, and humanitarian challenges.

-

By Sondoss Al Asaad

Youssef Raggi’s diplomatic derailment

When will Lebanese leadership restore institutional discipline?

BEIRUT—Handpicked by the Lebanese Forces (LF), Lebanon’s Foreign Minister Youssef Raggi has, since taking office, behaved less like a custodian of national diplomacy and more like a partisan activist focused only on a narrow ideological agenda.

-

By Mohammad Khatibi

Expert says Chinese investment in Iran difficult under sanctions, but possible with determination

TEHRAN – In the midst of intensifying regional tensions and the enduring weight of Western sanctions, the future of China–Iran relations remains a subject of growing international interest. To better understand the dynamics shaping Beijing’s approach to Iran, The Tehran Times spoke with Professor Hongda Fan, director of the China–Middle East Center at Shaoxing University.

-

Ethiopian parliament speaker says expanding bilateral ties with Iran a ‘priority’

TEHRAN – Ethiopia’s Parliament Speaker, Tagesse Chafo, said Saturday that strengthening and expanding bilateral relations with Iran is a top priority, highlighting opportunities for deeper political, economic, and cultural cooperation between the two countries amid their recent BRICS membership.

Politics

-

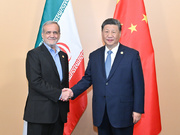

Tehran, Beijing reaffirm close bilateral ties in all areas

TEHRAN – Iran and China have emphasized their commitment to further enhancing mutual relations, highlighting the long history of Tehran-Beijing ties over decades.

-

Non-Iranian oil tanker smuggling fuel seized in Sea of Oman

TEHRAN – Iran has detained a foreign oil tanker accused of carrying contraband fuel in the Sea of Oman.

-

Iran and the civilizational discourse of Islam

TEHRAN - As the Western-centered global order continues to move towards erosion and nations increasingly turn back to their historical identities in search of a renewed place in the world, Iran’s role in shaping the civilizational discourse of Islam has become more significant than ever.

Sports

-

Iran swimmer Gholami dreams of competing in Olympics

TEHRAN – Young Iranian swimming sensation Mohammadmahdi Gholami has revealed his ambition to compete at the Olympic Games.

-

Iran runners-up at 2025 Asian Youth Para Games

TEHRAN – Iran finished second at the 2025 Asian Youth Para Games (AYPG) in Dubai.

-

Iran stripped off of hosting rights in 2027 FIBA World Cup qualifiers

TEHRAN – Iran’s national basketball team will be forced to play their home games in the 2027 FIBA Basketball World Cup Asian qualifiers at a neutral venue.

Culture

-

Irreparable Defeat cartoon festival to highlight themes of resistance, justice

TEHRAN- The third edition of the Irreparable Defeat Cartoon and Caricature Competition will be held on the themes the irreparable defeat of the Zionist regime in the Al-Aqsa Storm operation, the defeat of the Zionist regime in the Operation True Promise III, and the martyrs of the 12-day war.

-

Iranian artist showing artwork in “The Temple of Dreams” international exhibition in Italy

TEHRAN – An artwork by the Iranian artist Shirin Mohseni-Nasab is present at the international exhibition “The Temple of Dreams” in Lecce, Italy.

-

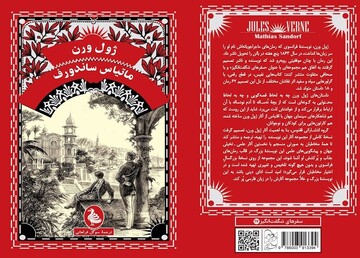

Jules Verne’s “Mathias Sandorf” published in Persian

TEHRAN – The Persian translation of the 1885 adventure book “Mathias Sandorf” written by the French writer Jules Verne has been released in the bookstores across the country.

Economy

-

Caspian maritime consortium, ports expansion highlight Iran’s push for sea-based growth

TEHRAN – Iran plans to establish a maritime consortium in the Caspian Sea with the participation of private-sector companies from Iran and Russia in the coming months, the head of the Ports and Maritime Organization (PMO) said on Saturday.

-

Tehran to host next Iran-Qatar Joint Economic Committee meeting in late Jan. 2026

TEHRAN- The 11th Iran-Qatar Joint Economic Committee meeting is planned to be held in Tehran in the beginning of the Iranian calendar month Bahman (late January2026), Iranian energy minister announced.

-

Iran, Kazakhstan private sectors sign 9 co-op agreements during Astana visit

TEHRAN – Private-sector representatives from Iran and Kazakhstan signed nine cooperation agreements during a visit by a trade delegation from the Iran Chamber of Commerce to Astana, aimed at expanding bilateral business ties.

Society

-

Ministry of Education inaugurates new school in Qatar

TEHRAN – Education Minister Alireza Kazemi inaugurated a new school on Saturday for Iranians residing in Qatar.

-

ICRC seeks to boost co-op with IRCS

TEHRAN – Vincent Cassard, the representative of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), has highlighted the need to expand collaborations with the Iranian Red Crescent Society (IRCS) in 2026.

-

Iranian students shine at World Mathematics Team Championship 2025

TEHRAN – Five Iranian female students have won gold medals at the World Mathematics Team Championship (WMTC) 2025 held from December 3 to 8 in Bangkok, Thailand.

Tourism

-

Iran, Greece discuss joint action plan to expand tourism, heritage cooperation

TEHRAN – Iran’s Minister of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts Seyyed Reza Salehi-Amiri and Greek Tourism Minister Olga Kefalogianni met in Athens on Thursday to discuss plans for expanding cooperation in tourism, museums and cultural heritage.

-

Iran, India discuss expanding cultural heritage cooperation

TEHRAN – Ali Darabi, Iran’s deputy minister for cultural heritage, has met with Vivek Agarwal, India’s deputy minister of culture, in New Delhi to discuss expanding bilateral cooperation in the field of cultural heritage.

-

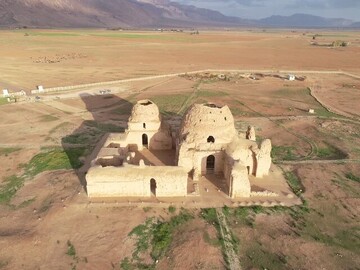

10 conservation, organizing projects planned for Sassanid World Heritage site of Fars

TEHRAN--Director of Sassanid Landscape World Heritage site of Fars province announced the completion of administrative procedures to sign contracts for 10 new conservation and organizing projects in two world heritage sites of this landscape.

International

-

Eurovision: A measure of international sentiment against Israel

TEHRAN - Israel may feel it has weakened Hamas and Hezbollah and now entertains the illusion that it is time to create a “new Middle East” and a “Greater Israel.” Yet these fleeting feelings of victory have come at the cost of unspeakable tragedy for civilians in Gaza.

-

Israel exploiting Syrian instability to expand territorial control, Lebanese analyst warns

TEHRAN- As Syria marks one year since the fall of the Assad government, the country faces unprecedented political, social, and humanitarian challenges.

-

Youssef Raggi’s diplomatic derailment

BEIRUT—Handpicked by the Lebanese Forces (LF), Lebanon’s Foreign Minister Youssef Raggi has, since taking office, behaved less like a custodian of national diplomacy and more like a partisan activist focused only on a narrow ideological agenda.

Video Comment

-

Ayatollah Khamenei’s vision of freedom and humanity discussed in intl. conference

-

Iran hosts SCO joint anti-terror drills

-

Holy Mary Metro Station marks interfaith unity in Tehran

-

Academics analyze social dimensions of Resistance in Tehran conference

-

Culture minister highlights year of progress in arts, global image enhancement

Most Viewed

-

Leader: Enemy seeks Iranian mind shift as only path towards success

-

Persian art of Ayeneh-Kari added to UNESCO intangible heritage list

-

Iran, Greece discuss joint action plan to expand tourism, heritage cooperation

-

Putin calls strategic pact with Iran a ‘turning point’ as implementation advances

-

Iran proposes academic cooperation council at Ancient Civilizations Forum in Athens

-

Tucker Carlson condemns ‘abominable’ human cost in Gaza after visiting maimed children

-

U.S. actions, not Iran’s behavior, triggered nuclear standoff: Chinese analyst

-

Who benefits from a disarmed Lebanon?

-

Expert says Chinese investment in Iran difficult under sanctions, but possible with determination

-

Beirut’s cautious letter to Tehran

-

‘This is piracy’: Iran condemns US seizure of oil tanker off Venezuelan coast

-

Tehran condemns US tightening of restrictions on Iran’s UN Diplomatic Mission

-

Israel’s aggressive blueprint: A rebuttal to Lebanon’s pro-Israel propaganda

-

Ethiopian parliament speaker says expanding bilateral ties with Iran a ‘priority’

-

Nowruz-observing countries meet in New Delhi on safeguarding shared heritage