-

2026-02-27 23:08

2026-02-27 23:08

By Mona Hojat Ansari

A shaky step forward

Iran and US advance nuclear talks but there are no clear signs Washington will keep diplomacy alive

TEHRAN – Iran and the United States held what Iranian officials described as their “most serious” round of nuclear negotiations in Geneva on Thursday, agreeing to continue discussions in Vienna next week, but developments across the region suggest Washington may still be leaning toward a military confrontation—an outcome that several regional governments have warned would be devastating.

-

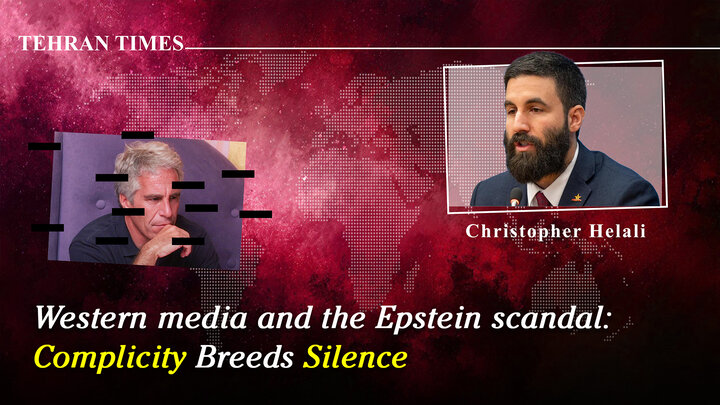

By Shahrokh Saei

From headlines to hostilities: How Israel and US media beat the drums of war with Iran

TEHRAN – The latest episode of The Tucker Carlson Show has intensified debate over who is pushing the United States toward confrontation with Iran.

-

By Sondoss Al Asaad

Lebanon: IMEC pressures, the fading ‘mechanism,’ and the open debate on normalization

SOUTH LEBANON — Lebanon today stands at the intersection of three converging tracks: the collapse of the ceasefire supervisory “Mechanism,” mounting geopolitical pressure through the India–“Middle East” –Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), and deep uncertainty surrounding parliamentary elections.

-

By Wesam Bahrani

From denial to doctrine: The Zionist approach to Palestinians

TEHRAN – The Israeli regime’s approach to the Palestinian Nakba has shifted from denying it happened to using indiscriminate force as a deliberate policy tool.

-

By Xavier Villar

France turns political speech into ‘glorifying terrorism’

MADRID – In the photographs of Mahdieh Esfandiari that circulated in the media during her judicial process in France, one detail drew disproportionate attention. It was the veil. Not because a woman wearing hijab is an anomaly in contemporary Europe, but because of what that garment condensed in this specific case: an Iranian academic, educated at Lumière Lyon 2 University, facing a criminal court for words published on Telegram.

-

How hundreds were killed in Iran’s riots, according to an opposition outlet

TEHRAN – One of Telegram’s most prominent anti–Islamic Republic channels has circulated a list of locations where rioters were killed during Iran’s January unrest, revealing that the vast majority of those sites were police stations and military bases that had come under attack.

Politics

-

‘Practical’ proposals discussed in Iran-US talks: Tehran

TEHRAN- Iran says that “important” and “practical” proposals were advanced during negotiations in Geneva on Thursday morning on Iran’s nuclear program and the lifting of sanctions.

-

Offense within a defensive formula

LONDON - Two factors arising from miscalculation may prompt the U.S. to attack Iran. The first miscalculation is that Iran is in its weakest state, as claimed by U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio in his address to Congress.

-

Six terrorists killed in IRGC ambush in southeast Iran

TEHRAN – In an ambush on Tuesday night, troops from the Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC) have killed six members of the Jaish al-Adl (known in Iran as Jaish-al-Zulm) terrorist group in an ambush near the border city of Saravan in the southeastern province of Sistan-Baluchestan.

Sports

-

Iran to play friendly matches to prepare for 2026 Asian Beach Games

TEHRAN – Iran beach soccer coach Ali Naderi said on Friday Team Melli are going to play several friendly matches as part of preparation for the 2026 Asian Beach Games.

-

Iran’s fixtures at 2027 FIBA Basketball World Cup Asian Qualifiers announced

TEHRAN - The Iran men's national basketball team will begin their campaign in the second window of the 2027 FIBA Basketball World Cup Asian Qualifiers on Friday, facing Jordan men's national basketball team.

-

Tractor beat Gol Gohar in 2025/26 PGPL

TEHRAN - Tractor football team defeated Gol Gohar Sirjan 1-0 in Matchweek 22 of the 2025/26 Persian Gulf Pro League (PGPL) on Thursday night.

Culture

-

“Mahfel” Quranic program expands global reach with multilingual broadcast

TEHRAN- The popular Iranian Quranic television program “Mahfel” is now dubbed into four languages and aired on eight international networks, as the show continues to expand its reach beyond Iran and attract audiences across the Muslim world.

-

“Great Stories by Nobel Prize Winners” published in Persian

TEHRAN – The Persian translation of the book “Great Stories by Nobel Prize Winners” edited by Leo Hamalian and Edmond L. Volpe has been released in the bookstores across the country.

-

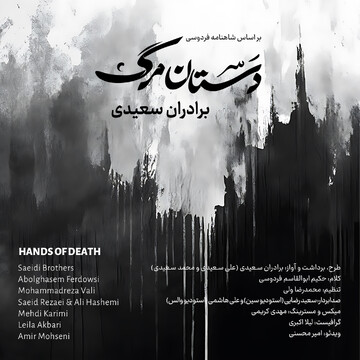

Vocalist brothers release new Shahnameh-inspired musical piece

TEHRAN- The Saeidi Brothers, a traditional Iranian twin duo comprising Ali and Mohammad Saeidi, have released a new musical piece titled “Dastan-e Marg” (Hands of Death), offering a distinct narrative inspired by the Shahnameh, the epic masterpiece of the Persian poet Ferdowsi.

Economy

-

Iran's steel output rises 15% to 2.6m tons in January: WSA

TEHRAN – Iran’s crude steel production rose 15.1 percent year-on-year to 2.6 million tons in January 2026, according to the latest data released by the World Steel Association (WSA).

-

Iran, Turkmenistan hold strategic rail corridor talks in Sarakhs

TEHRAN – Senior rail officials from Iran and Turkmenistan met at the Sarakhs international border station to discuss expansion of bilateral cooperation and development of regional rail corridors.

-

Iranian oil exports reach 2.2m bpd in February

TEHRAN – Iran’s crude oil and condensate exports rose to 2.2 million barrels per day (bpd) in February, up 50 percent from the average of the previous three months, according to data from energy cargo tracking firm Kpler.

Society

-

DOE warns UN: U.S. military presence endangers Persian Gulf, Sea of Oman biodiversity

TEHRAN – The head of the Department of Environment (DOE), Shina Ansari, has written a letter to UN Secretary-General António Guterres, warning that the U.S. military presence endangers biodiversity in the Persian Gulf and the Sea of Oman.

-

Iran, Egypt explore potential to enhance sci-tech ties

TEHRAN – The head of the Ministry of Science, Research and Technology’s center for international scientific cooperation, Ehsan Qaboul, and the head of the Egyptian Interests Section in Tehran, Mohammed Zia, have discussed avenues to expand educational, scientific, and technological cooperation between the two countries.

-

Over 490 rare diseases identified in Iran

TEHRAN – A total of 492 rare diseases have been identified in the country, according to an official with the health ministry.

Tourism

-

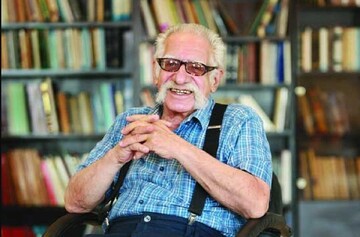

Museum director commemorates Arfa’i as pioneer of Elamite, Old Babylonian studies

TEHRAN – The head of the museum at Persepolis on Thursday marked the memory of professor Abdolmajid Arfa’i, an Elamite scholar and researcher of ancient Elamite and Akkadian languages, who died on Wednesday at the age of 86 after a period of illness.

-

Qatar Airways maintains daily Tehran-Doha flights

TEHRAN – Qatar Airways will continue operating daily flights on the Doha-Tehran-Doha route until June 30, Tehran’s Imam Khomeini Airport City said, dismissing reports of a suspension.

-

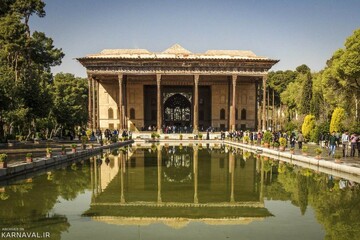

Safavid-era cannon to undergo conservation process

TEHRAN – A Safavid-era cannon in Isfahan’s 17th-century Chehel Sotoun Palace has entered a process of conservation and revised display after years of being kept in unsuitable conditions, the site’s director said.

International

-

From Gaza to the Red Sea: Why Israel now calls Yemen its ‘nightmare’

TEHRAN – Yemen’s Ansarullah movement has been a thorn in the side of Israel since the inception of the genocidal war on Gaza. From the earliest weeks of Israel’s military campaign in October 2023, Sana’a made clear that it would not remain a passive observer. By mid-November 2023, the Ansarullah movement had begun targeting vessels it identified as linked to Israel or bound for Israeli ports.

-

Lebanon: IMEC pressures, the fading ‘mechanism,’ and the open debate on normalization

SOUTH LEBANON — Lebanon today stands at the intersection of three converging tracks: the collapse of the ceasefire supervisory “Mechanism,” mounting geopolitical pressure through the India–“Middle East” –Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), and deep uncertainty surrounding parliamentary elections.

-

From denial to doctrine: The Zionist approach to Palestinians

TEHRAN – The Israeli regime’s approach to the Palestinian Nakba has shifted from denying it happened to using indiscriminate force as a deliberate policy tool.

Most Viewed

-

Oman, Iran confirm ‘significant progress’ in Iran-US talks, technical discussions to start Monday

-

Iran, US hold nuclear talks in Geneva, Oman presents Tehran’s proposals to US

-

Iran, US restart talks after a break

-

Tehran says Iran-US talks conducted with ‘great seriousness’

-

Iran Armed Forces to take out US troops, equipment in case of war: senior general

-

Oman FM: Iran, US ‘exchanging creative and positive ideas’

-

‘Practical’ proposals discussed in Iran-US talks: Tehran

-

A shaky step forward

-

From headlines to hostilities: How Israel and US media beat the drums of war with Iran

-

US insists on ‘limiting’ Iran's enrichment in Geneva talks, source says

-

Ayatollah Khamenei and the strategic logic of the Islamic Republic

-

Qatar Airways maintains daily Tehran-Doha flights

-

How hundreds were killed in Iran’s riots, according to an opposition outlet

-

From Gaza to the Red Sea: Why Israel now calls Yemen its ‘nightmare’

-

Iran, Turkmenistan hold strategic rail corridor talks in Sarakhs