-

2026-02-13 22:11

2026-02-13 22:11

By Sheida Sabzehvari

Tehran reiterates missile red line as Israel pushes to sink nuclear talks

Shamkhani repeats Iran ready for potential war

TEHRAN – Iran will not acquiesce to U.S. demands regarding its missile program, a senior Iranian defense official said, warning that the country is prepared to respond decisively should Washington choose to try out war for a second time.

-

Leader thanks Iranian people for ‘great deed’ at Bahman 22 rallies

TEHRAN – Leader of the Islamic Revolution Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Khamenei has thanked the Iranian nation for their massive participation in Wednesday’s 22nd of Bahman rallies, stating that the huge crowds have left enemies who hoped for Iran’s surrender “disappointed” and in despair.

-

Iranian FM scorns Miriam Adelson for her unsubstantiated claims

TEHRAN – Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi has censured Miriam Adelson, the widow of casino mogul and billionaire Sheldon Adelson, for making false claims against Iran in her Israel Hayom publication on February 11.

-

By staff writer

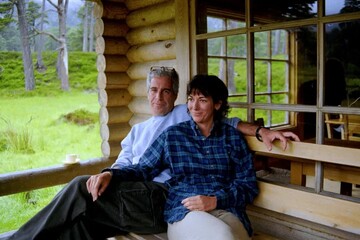

The Epstein files: A glimpse into the rot beneath America’s ruling class

TEHRAN – The newest attention on the Epstein files has torn the mask off the American system once again, showing just how deep the decay runs inside the country’s political and social power structure.

-

By Sondoss Al Asaad

Yemen commemorates historic Feb. 11 victory against U.S. occupation

BEIRUT — Every year, Yemenis gather to commemorate February 11, marking one of the most significant turning points in the country’s modern history.

-

By Wesam Bahrani

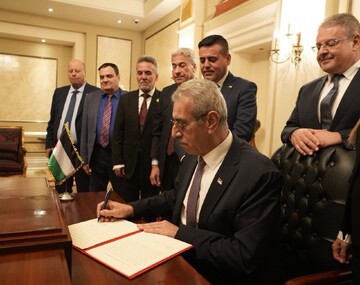

The fate of the Palestinian technocratic committee

TEHRAN – Despite being announced several weeks ago, the Palestinian National Committee established to manage the Gaza Strip has yet to begin operating in the enclave.

Politics

-

Iran sends Jaam-e-Jame 1 satellite into space

TEHRAN - The “Jaam-e-Jam 1” satellite belonging to the Islamic Republic of Iran’s Broadcasting Organization (IRIB) has been successfully launched into space from the Baikonur Cosmodrome, a spaceport in the Kazakh city of Baikonur.

-

Woman, Life, Epstein

While the Western world presents itself as the standard-bearer of women’s rights, newly released documents from the Jeffrey Epstein case once again reveal how these same self-proclaimed structures turned a blind eye for years to the systematic abuse of young girls—while simultaneously transforming the death of a girl in another country into a tool of political symbolism.

-

Nuclear chief hails Iran’s 'miraculous' progress despite severe sanctions

TEHRAN - Mohammad Eslami, the director of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI), says the Islamic Republic has made outstanding progress in the nuclear industry despite extreme pressure from its foes.

Sports

-

Esteghlal Khuzestan edge Fajr Sepasi: 2025/26 PGPL

TEHRAN – Esteghlal Khuzestan secured a narrow but valuable 1–0 victory over Fajr Sepasi on Friday in Matchweek 21 of the 2025/26 Persian Gulf Professional League (PGPL).

-

Ahmadabbasi’s goal nominated for AFCFutsal2026 favorite goal

TEHRAN – The AFC Futsal Asian Cup Indonesia 2026, which concluded on Saturday, dazzled fans with a total of 166 goals as Iran national futsal team powered their way to a record-extending 14th continental title.

-

Iran handball sets sights on future goals, Pakdel says

TEHRAN – Alireza Pakdel, head of Iran handball federation, is prioritizing long-term development over short-term results.

Culture

-

“Pocket Tales” book series presenting works of prominent classical authors in Persian

TEHRAN – Amir Kabir Publications in Tehran is publishing long stories and short novels by prominent classical authors in pocket-sized editions in Persian.

-

IAF to show “The Duchess of Malfi”

TEHRAN – The Iranian Artists Forum (IAF) in Tehran will screen and review the filmed theater “The Duchess of Malfi” directed by Dominic Dromgoole on Wednesday.

-

“Land of Angels” triumphs at 44th Fajr Film Festival

TEHRAN- Iranian director Babak Khajehpasha’s “Land of Angels” was named best film at the 44th Fajr Film Festival during the closing ceremony held at Tehran’s Vahdat Hall on Wednesday.

Economy

-

Pezeshkian announces $2.5b allocation for transport corridor development

TEHRAN – President Masoud Pezeshkian has announced an unprecedented $2.5 billion allocation for the development of Iran’s transport corridors, describing the sector as a top government priority.

-

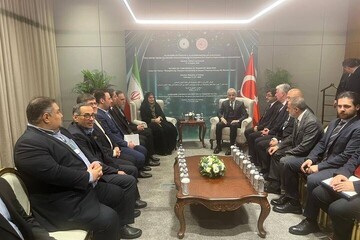

Iran, Turkey discuss new rail link, broader transport cooperation

TEHRAN – Iran and Turkey have discussed expanding transport cooperation, including a new rail connection at the Cheshmeh Soraya–Aralik border crossing and the revival of passenger train services between Tehran and major Turkish cities, Iran’s Transport Minister said.

-

Iran says Uzbek truck traffic surges 117% in 2025 after tariff removal deal

TEHRAN – Traffic by Uzbek transport fleets to Iran rose 117 percent in 2025 from a year earlier, while Iranian fleet traffic to Uzbekistan increased 18 percent, Iran’s transport and urban development minister said, citing a bilateral roadmap and the mutual removal of a $400 fee.

Society

-

National research, technology network for Persian medicine being launched

TEHRAN – The health ministry’s traditional medicine is developing a national research and technology network for Persian medicine to integrate scientific and technological efforts to enhance Persian medicine’s status and expand the value chain of medicinal plants.

-

DOE, Education Ministry plan to develop environmental education curriculum

TEHRAN – The Department of Environment (DOE) and the Education Ministry have discussed the possibility of developing a national education curriculum to promote environmental responsibility and awareness among children.

-

Intl. students take first Persian language proficiency test

TEHRAN – The National Education Assessment Organization, in cooperation with the Organization of Students Affairs, held the first Persian language proficiency test for international students in Tehran on Thursday.

Tourism

-

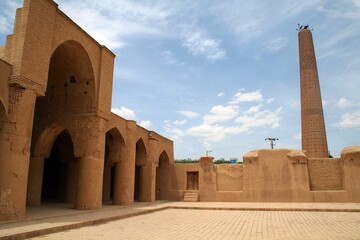

Damghan proposed as hub for eastern Iran civilizational studies

TEHRAN– Minister of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts on Thursday called for Damghan in Semnan province to be developed into a center for civilizational studies in eastern Iran, stressing the need for scientific protection and integrated management of two major historical sites in the city.

-

Minister suggests formation of spiritual tourism triangle in Semnan province

TEHRAN – Iran’s Minister of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts, Seyyed Reza Salehi-Amiri, on Thursday called for the formation of a spiritual tourism triangle stretching from Shahroud to the capital city of Semnan, during a visit to eastern Semnan province.

-

New legal measures under consideration to curb graffiti at Persepolis

TEHRAN – Iranian authorities plan to intensify legal action against graffiti and vandalism at the UNESCO-listed site of Persepolis, a provincial official said on Friday.

International

-

The Epstein files: A glimpse into the rot beneath America’s ruling class

TEHRAN – The newest attention on the Epstein files has torn the mask off the American system once again, showing just how deep the decay runs inside the country’s political and social power structure.

-

The fate of the Palestinian technocratic committee

TEHRAN – Despite being announced several weeks ago, the Palestinian National Committee established to manage the Gaza Strip has yet to begin operating in the enclave.

-

Yemen commemorates historic Feb. 11 victory against U.S. occupation

BEIRUT — Every year, Yemenis gather to commemorate February 11, marking one of the most significant turning points in the country’s modern history.

Most Viewed

-

Tehran reiterates missile red line as Israel pushes to sink nuclear talks

-

Iran elected as vice-chair of UN Commission for Social Development

-

The Epstein files: A glimpse into the rot beneath America’s ruling class

-

Pezeshkian announces $2.5b allocation for transport corridor development

-

The fateful dilemma of Iran’s economy

-

Iranian FM scorns Miriam Adelson for her unsubstantiated claims

-

Iran sends Jaam-e-Jame 1 satellite into space

-

Top Russian official says Moscow standing by Iran

-

Iran, Turkey discuss new rail link, broader transport cooperation

-

Nuclear chief hails Iran’s 'miraculous' progress despite severe sanctions

-

The fate of the Palestinian technocratic committee

-

Yemen commemorates historic Feb. 11 victory against U.S. occupation

-

Leader thanks Iranian people for ‘great deed’ at Bahman 22 rallies

-

Woman, Life, Epstein

-

European powers face backlash over ‘misinformation’ campaign against Francesca Albanese