Cinema Museum reviews Kiarostami’s “Fellow Citizen”

TEHRAN – Abbas Kiarostami’s 1983 medium-length documentary “Fellow Citizen” was shown at the 45th “Documentary Nights” program of the Cinema Museum of Iran in the north of Tehran on Monday.

Following the screening, a discussion session was held with Pirooz Kalantari, documentary filmmaker, and Robert Safarian, documentary filmmaker and film scholar. The session focused on the film and its significance within Iranian documentary cinema, Honaronline reported.

In July 1983, lawmakers in Tehran decided to close off a section of the capital to regular traffic. Only drivers with special permits could cross the roadblocks set up at various intersections leading to the restricted zone.

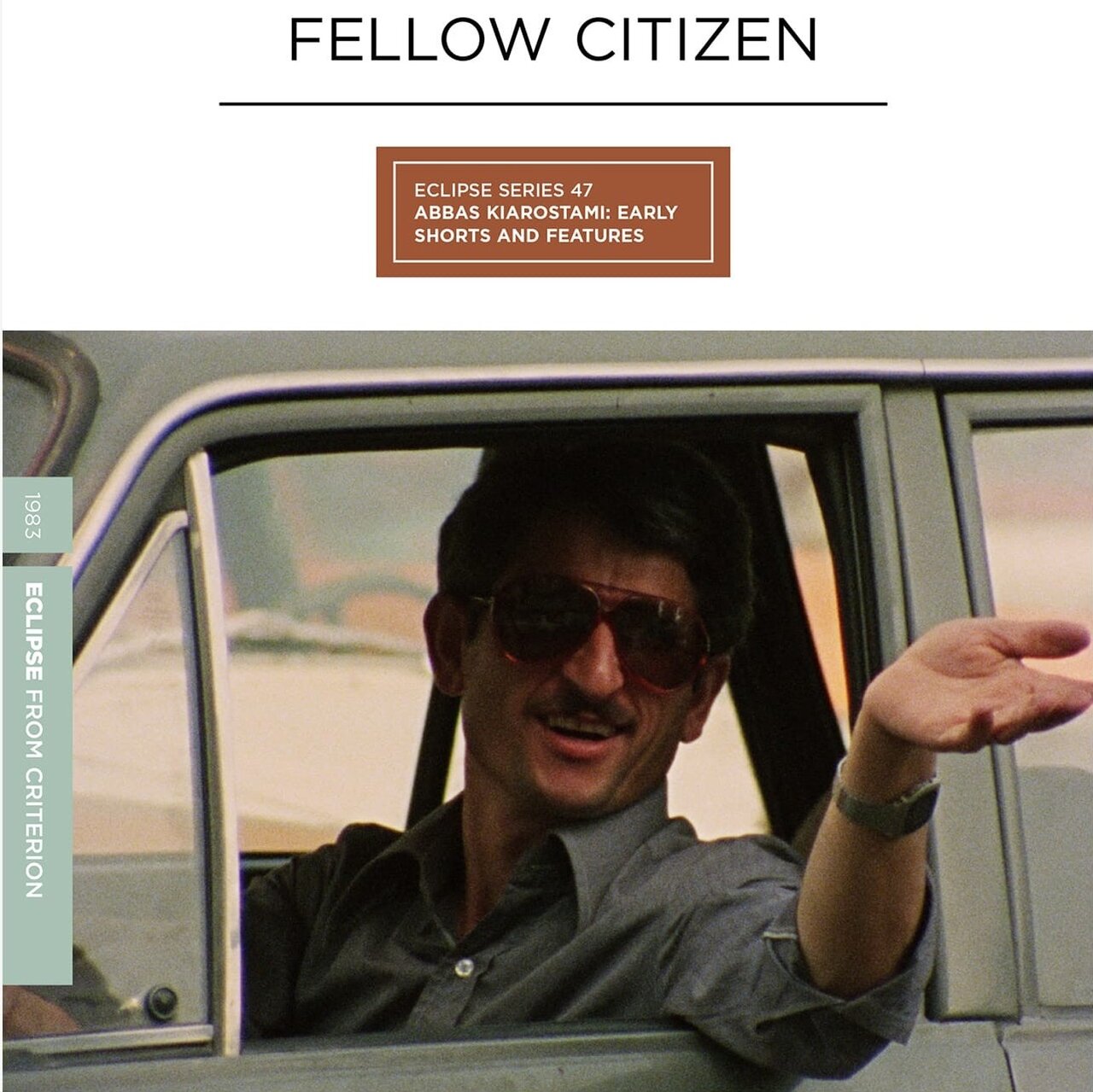

Kiarostami’s fascination with both Tehran car culture and the uses of power in postrevolutionary society combine in this documentary about a traffic officer assigned to enforce driving restrictions in central Tehran. The officer, a rock star in his own world, remains coolly authoritative as he faces a steady stream of exasperated motorists.

Many of Kiarostami’s films are built on a deceptively simple premise. In this 51-minute work, he uses a telephoto lens to film a busy intersection in Tehran, where a traffic cop is tasked with letting through only cars that have a permit. This produces fascinating exchanges between the officer and the drivers, who plead with him to let them pass.

Those without a permit try to convince him that their case is special: they need to rush to a nearby hospital, for example, quickly drop something off at a shop, or simply get to work. One driver even produces an X-ray to back up his claim.

Amid the ever-growing traffic chaos, it’s the officer’s job to decide who to allow through. He is no harsh authority figure, but someone open to the inventive arguments of the motorists.

The documentary was produced by the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children & Young Adults (also known as Kanoon). However, “Fellow Citizen” was a work of non-fiction and not about children.

For the entire duration, Kiarostami’s camera confines itself to telephoto lens close-ups on one traffic warden’s attempts to regulate the undammed flow of cars attempting to drive into an area recently restricted by Tehran’s new traffic laws. Unwinding their car windows, every driver makes their case on why they should be exempt from the rules: certain motorists plea for leniency with the traffic cop by insisting they’ll be back out in 15 minutes; a few more impatient commuters simply drive straight through despite the outraged protests of this uniformed human bollard whose hapless task seems increasingly overwhelming as the film goes on.

Kiarostami’s interest in cars as a liminal space of interaction and conversation, lying somewhere between the private and the public, is combined in “Fellow Citizen” with the motif of quest narratives so present in Persian poetic and storytelling traditions. Every driver here is on a quest of their own, needing to go through this checkpoint guarded by the traffic cop. And so, drivers must use all of their wits, their storytelling skills, their resourcefulness (a trait so often seen in Kiarostami’s child protagonists) in order to get past this barrier and proceed in their quest. Some make it through; others do not.

As the title suggests, “Fellow Citizen” is on one level a sociological parable about ideas of citizenship. The use of storytelling and the occasional white lie by many of these drivers, in most cases without realizing that a zoom lens is filming them from afar, serves as a reminder of the performativity of all societal interactions. It also draws attention to another permeable boundary: not just that of the officer’s blockade protecting the forbidden traffic zone, nor of the car windows poising those inside the automobiles between the public and private spheres. There is also, as so often in Kiarostami, the thin line between fiction and reality.

“Fellow Citizen” represented for Kiarostami his first foray into medium-length documentary. In the editing room, he reduced 18 hours of footage into the 50 minutes of the final cut, forming an early experiment in his later expert ability to mould fictional narrative out of material rooted in reality.

Indeed, on several occasions, bemused drivers do notice the camera and ask the traffic officer whether a film is being made. Already in this relatively early stage of Kiarostami’s filmography, he demonstrates an attraction to simultaneously observing reality while intervening within it.

SS/SAB

Leave a Comment