At Tchogha Zanbil, a living monument to Elamite faith and engineering

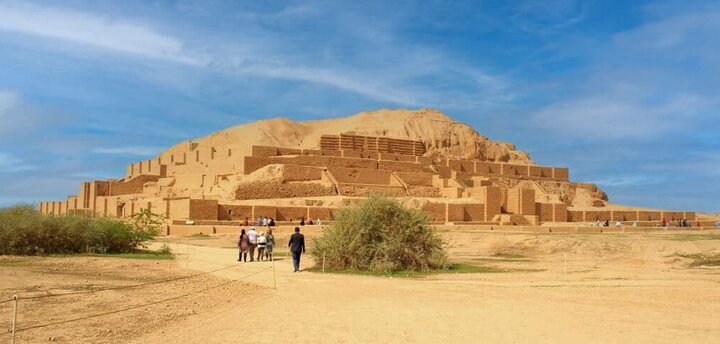

On a serene plain in southwestern Iran, the stepped ziggurat of Tchogha Zanbil has stood for more than 3,500 years, making it the best-preserved ziggurat outside Mesopotamia and one of the rare surviving monuments of the Elamite civilization.

“This is not just a building but a comprehensive religious city,” said Atefeh Rashnoei, who was serving as director of the Tchogha Zanbil World Heritage site at the time of the interview. “It is living evidence of belief, nature, and social order in ancient Elam.”

She underlined that Tchogha Zanbil was constructed precisely according to the cardinal directions, without the slightest error, adding that this accuracy reflects the Elamites’ detailed knowledge of the movement of the sun, sunrise and sunset, and the relationship between heaven and earth. She underlined such an understanding is among the reasons the site was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as a symbol of human ingenuity.

According to Rashnoei, Tchogha Zanbil was designed exclusively for religious purposes. Unlike ancient cities built for everyday life, the complex functioned as a ceremonial center, intended for worship and for expressing harmony among different Elamite and Mesopotamian deities.

“We are now standing between the first and second surrounding enclosures,” she explained. “In this area, there were temples dedicated to different gods and goddesses, such as Adad and Shala. Their presence together reflects peaceful coexistence among divine powers.”

The city was founded around 1250 BC by the Elamite king Untash-Napirisha, who dedicated it to the gods Inshushinak and Napirisha. Construction followed precise geographic orientation, aligned with cardinal directions, a level of accuracy that continues to impress archaeologists today.

One of the most striking features of Tchogha Zanbil, Rashnoei said, is a principle deeply rooted in Iranian architecture, which is “privacy”.

“In Elamite architecture, there is no direct entrance into a sacred space,” she said. “To reach the altar, a worshipper had to pass through turns and angled corridors. This gradual transition prepared the visitor spiritually.”

Rashnoei, who is the director of the Tchogha Zanbil and Haft Tappeh World Heritage Base, noted that this idea of indirect access has endured in Iranian architecture for millennia, appearing later in mosques, houses and gardens.

At the heart of the complex stands the ziggurat itself, which is a five-story structure with a square base measuring 105 by 105 meters.

“Unlike Mesopotamian ziggurats, this one was built directly from the ground up,” Rashnoei said. “All its levels have foundations that reach into the soil. Nothing is simply stacked on top.”

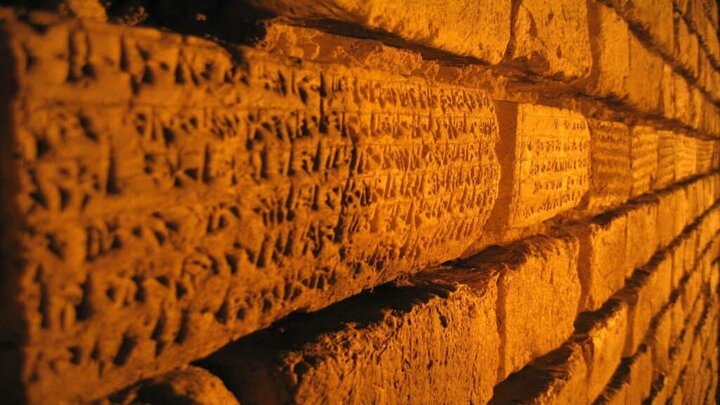

“Every ten rows of bricks, the inscription repeats,”Rashnoei said. “King Untash-Napirisha introduces himself, dedicates the building to the gods, and ends with a famous Elamite curse against anyone who harms the monument.”

For scholars, these inscriptions are invaluable records of language, religion and royal authority in ancient Iran.

In response to a question about the footprints found at the site, she said many are visible, explaining that when the freshly laid clay covering was installed in ancient times, a child or an animal may have passed through and left impressions behind, and that this was therefore not an unusual phenomenon.

Another defining feature of Tchogha Zanbil is its advanced rainwater management system, which is a rare achievement for its time.

She also cited the advanced rainwater management system as another outstanding feature of the complex, saying that provisions for rainwater had been made from the very beginning. Rainwater, she explained, was channeled 3,500 years ago through gutters and ceramic pipes into large jars around the temple, where it was kept as sacred water. Care was always taken to preserve this water so that none was wasted. One intact jar, discovered by [the Ukrainian-born French archeologist Roman] Ghirshman, is now kept at the National Museum of Iran. No complete jars remain at the site today, as all the others are broken.

Rashnoei said the temple also had a designated area for cooking, as traces of burnt wood and cooking remains have been found. Remains of royal tombs, skeletons, animal and human figurines, particularly statues linked to fertility and ritual sacrifices, have been discovered in various temples, shedding light on the religious and social practices of the Elamites.

A site under constant threat

Preserving Tchogha Zanbil is a demanding and costly task. The bricks vary in color and strength because of high soil salinity and differences in firing temperatures, making them vulnerable to weather.

“This is one of Iran’s most sensitive World Heritage sites,” Rashnoei said. “Mud-brick conservation is extremely specialized, slow and expensive.”

She said the cost of restoring just one square meter of mud-brick structure is a considerable value, and each [restoration] project typically require at least six months. Speeding up the process, she added, risks damaging the site’s authenticity.

As mentioned by the official, the conservation policy at Tchogha Zanbil is based on in-situ preservation. No reconstruction or new additions are permitted.

“About 90 percent of what you see here is original Elamite material,” Rashnoei said. “Our interventions are limited to stabilizing structures and preventing moisture penetration.”

Recent heavy rains tested those efforts. Over three days, the site recorded 53 millimeters of rainfall, yet for the first time in eight years, no major collapse was reported.

“That is the result of continuous work by our conservation teams,” she said.

Despite these successes, Rashnoei said stable funding remains the site’s most urgent need. She estimates that an adequate funding is required for infrastructure, fencing, physical protection and scientific conservation.

“Protecting Tchogha Zanbil is a long-term commitment,” she said. “Without sustainable resources, gradual erosion is unavoidable.”

Looking ahead, the site management has drafted plans for limited tourism infrastructure, including service areas, a cultural café and a permanent handicrafts exhibition. Talks with local investors are underway, she said, but any development will remain secondary to conservation priorities.

A monument that still speaks

Excavated between 1951 and 1961 by the French archaeologist Roman Ghirshman, Tchogha Zanbil stands about 30 kilometers southeast of the UNESCO-listed Susa and 80 kilometers north of Ahvaz. UNESCO describes it as the largest ziggurat outside Mesopotamia and one of the clearest expressions of Elamite culture.

The ziggurat’s core is made of mud brick, while the exterior is faced with baked bricks. At its peak, the structure likely reached a height of about 52 meters, crowned by a temple. Today, it stands at roughly 25 meters. More than 30 different Elamite inscriptions have been identified across the site. Each temple had its own texts, but the most prominent inscriptions belong to the ziggurat itself.

“For us,” Rashnoei said as the sun lowered over the plain, “protecting Tchogha Zanbil means protecting a part of Iran’s identity and a chapter of human civilization that still has much to teach us.”

AM

Leave a Comment