Before refrigerators, Iran had Yakhchals: Where did summer ice come from?

GONABAD – Have you ever paused, while sipping a chilled sharbat or juice with ice cubes floating inside, or enjoying an iced tea or iced coffee, to wonder how people kept their drinks and food cool before modern refrigerators and ice makers existed? Did they have access to cold water during the scorching days of summer? To find the answers, one can look to the heart of Iran’s desert cities—places where architectural ingenuity and human adaptation to nature gave rise to remarkable structures known as yakhchals, or icehouses.

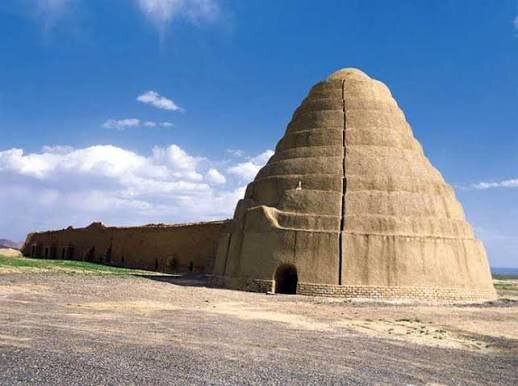

One such desert city is Gonabad, located in eastern Iran, in the southern part of Razavi Khorasan Province. About four kilometers northeast of Bidokht, as you travel through the hot, arid landscape, a domed structure by the roadside inevitably catches your eye. If curiosity gets better of you, you pull over and walk toward it. With every step closer, questions begin to form: What is this structure? Why was it built in the middle of the desert? What is the purpose of its dome? Was it a place of worship, or perhaps a storage facility for food?

Standing before it, you see a dome about five meters high, attached to a tall wall, with a small chamber beside it. Peering inside, a deep pit—also around five meters deep—comes into view. At this point, it becomes clear that you are facing a structure that appears simple at first glance, yet is remarkably complex and intelligent in design. Its secret soon reveals itself: this is the Kosar Icehouse, a structure dating back to the Qajar period.

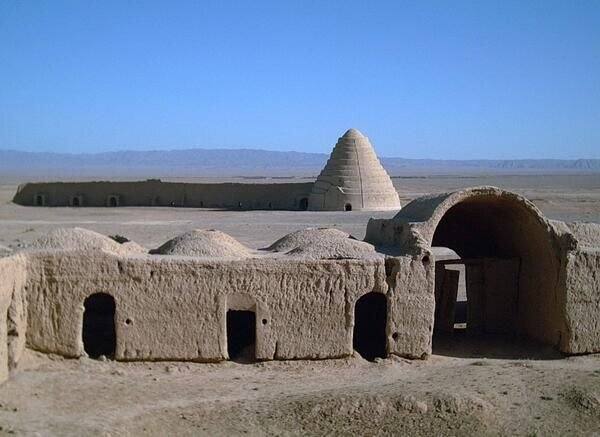

Icehouses were buildings in which people in the past produced ice naturally during winter and stored it for use throughout the summer. Relying on their specific architectural form and physical characteristics, these structures made it possible to preserve ice despite harsh climatic conditions. Typically, an icehouse consists of three main parts: a shading wall, ice-making pools, and an ice storage chamber.

In the Kosar Icehouse, the shading wall is located on the northern side of the building to block direct sunlight. At the base of this wall, rectangular pools about 30 to 40 centimeters deep were dug. During cold winter nights, small amounts of water—only a few millimeters deep—supplied by qanats or collected from rain and snow were poured into these pools. Once the first layer froze, another thin layer of water was added. This process was repeated night after night until the ice reached a thickness of 30 to 40 centimeters. This layered method allowed the ice to form more quickly and evenly.

Once the ice was ready, it was broken into pieces with axes and transferred into the storage chamber using hooks and ropes. The chamber, carved into clay soil in the shape of an inverted cone, is about five and a half meters deep. Its walls were built using compacted earth (chineh) and coated with a layer of mud mixed with straw, creating effective thermal insulation. To prevent the ice blocks from sticking together, straw or reeds were placed between them, and the top layer was covered with sacks filled with straw.

Above the storage chamber rises a double-shelled dome made of mud bricks and earth. The inner shell was constructed using a circular brick-laying technique, while the outer shell, built of compacted earth, has been covered with a straw-and-mud plaster during restoration. The choice of these materials, given their thermal properties, was highly deliberate and helped minimize heat penetration into the interior. The considerable height of the dome also allowed warm air to accumulate near the top, keeping the lower levels—where the ice was stored—cool.

To manage the water produced by the gradual melting of the ice, a small well was dug at the center of the chamber floor, preventing erosion of the walls. Another entrance, facing south, was constructed with a stairway leading down to the bottom of the chamber and was used to extract ice during the summer months. The small room beside the icehouse served as a storage space for tools and equipment used by the caretakers.

Icehouses were generally built outside residential areas, near farmlands or gardens, since the most important factors in site selection were access to clean water and sufficient open space. Contrary to popular belief, icehouses were not limited to desert regions. In water-rich and temperate areas such as Mazandaran, Gilan, and even western Iranian cities, these structures also played a significant role in ice supply. During summer, the produced ice was transported to markets by pack animals and sold at affordable prices, making it accessible even to low-income households.

From an architectural perspective, there are three main types of icehouses in Iran: domeless, tunnel-shaped, and domed. The Kosar Icehouse of Gonabad belongs to the domed type. Today, with the advent of mechanical refrigerators and industrial, hygienic methods of ice production, this traditional practice has completely fallen out of use, and many icehouses have become abandoned structures. Nevertheless, they remain valuable symbols of indigenous knowledge, climate-responsive architecture, and the creativity of Iranians in adapting to nature—an important part of the country’s cultural heritage, whose preservation and introduction serve as a bridge between our past and present.

Leave a Comment