‘The blame for resurrecting the insurgency in Afghanistan ultimately rests with the U.S.’

TEHRAN - The war in Afghanistan, which began on October 7, 2001, completed 17 years this week. More than 17 years after invading the country, the U.S.-led international coalition has reluctantly conceded defeat to insurgent groups, after miserably failing in counter-terrorism efforts. Today, security situation remains volatile, government is in disarray, terrorists are stronger than ever, and civilians continue to pay the heavy price.

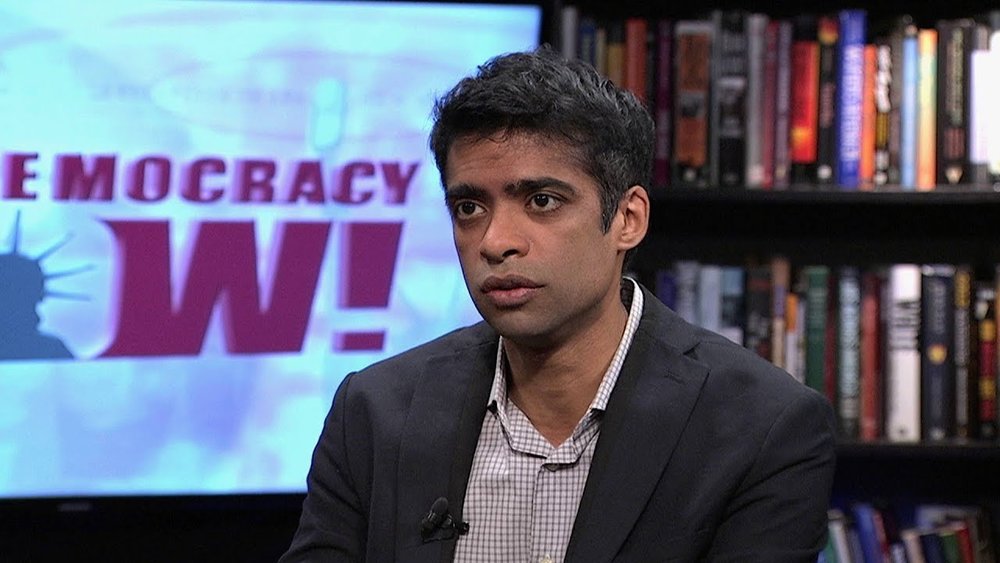

An acclaimed journalist and author, Anand Gopal has extensively reported from Afghanistan and the Middle East. He is the author of ‘No Good Men Among the Living: America, the Taliban, and the War through Afghan Eyes’, which focuses on U.S. invasion of Afghanistan and the failed war.

Through the dramatic stories of three Afghans caught in America’s war on terror, Gopal shows that the Afghan war, often seen as a hopeless quagmire and an intractable conflict, could in fact have gone very differently. This interview, originally published in Afghan Zariza a few years ago, was conducted by magazine editor Syed Zafar Mehdi.

Following are the excerpts:

Q. In your book ‘No Good Men Among the Living: America, the Taliban, and the War through Afghan Eyes’, you argue that the U.S. forces pressed the conflict in Afghanistan and resurrected the insurgency. Do you think the blame goes squarely on the U.S.?

A. I believe the blame for resurrecting the insurgency ultimately rests with the U.S., but blame for sustaining and continuing the insurgency is shared equally by the U.S. and Pakistan. Of course, the Afghan government is also to blame, but we cannot look at their actions independently of outside forces, since they are playing by the rules that outsiders set.

If we take a longer view, stretching back thirty years, I believe the U.S. and the Soviet Union are ultimately responsible for the conflict. On the one hand, the Soviet Union killed over a million and destroyed the country; on the other, the U.S. spread extremism and warlordism through their patronage of rebel groups. Furthermore, the U.S. and Saudi patronage in the 1980s transformed the Pakistani state, helping make the ISI what it is today.

Q. The top Taliban leadership, you claim, tried to surrender soon after the U.S. invasion. Why was the U.S. not willing to accept them?

A. The mood at the time was that, like Bush said, “You are either with us or against us.” America’s goal was to wage a war on terror, and the fact that its enemies were trying to switch sides was something that did not mesh easily with the ideology of counterterrorism.

Q. Your book tells the story of Afghan war through the lives of three Afghans: a Taliban commander, a tribal warlord and a village housewife. Is it just a co-incidence that they are all Pashtun?

A. No, it is not a coincidence—it is because the war is largely being fought in Pashtun areas. Moreover, all three are Pashtuns who lived at least part of the time in rural areas. There are many excellent works of reporting on Afghans living in cities, and in other parts of the country. However, there is very little about the lives of Pashtuns in rural areas, and I felt that it would be impossible to understand this war without exploring their experiences.

Certainly, there are many other facets of Afghanistan, and many other books waiting to be written about them, but I felt that this slice of life was necessary if we were to have a better picture of the conflict.

Q. You have not sufficiently highlighted the role of Pakistan in the resurgence of Taliban. Do you believe Pakistan’s intelligence agency Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) had no role to play in it?

A. The ISI played a major role in the resurgence of the Taliban by providing safe haven for Taliban leaders, influencing commanders, eliminating those they do not like, and generally by trying to control things behind the scenes. They are a major force of destruction in Afghanistan. However, this is well known, and as such my book focused on the U.S. role, which was much less-well known.

There is an idea floating around in some circles that Pakistan willed the Taliban back to life in 2002-4, but this simply does not appear to be the case. Rather, real grievances inside Afghanistan were the impetus for the Taliban’s regroupment, and Pakistan saw this process unfold and manipulated it for its own purposes.

Q. You have depicted Taliban as oppressed Pashtuns fighting against a corrupt government and foreign invaders. Could you elaborate on that?

A. I think it is important to distinguish between the reasons that led many to join the Taliban initially, and what the Taliban represents as a movement. It is true, and a matter of record, that many joined as a response to the torture, killings, air strikes, night raids, and other crimes committed by the foreign forces and their proxies.

You can travel through Deh Rawud district in Uruzgan, for example, and see many pro-government villages. But in neighboring Char Chino, the majority of territory is held by insurgents.

Why such differences? The reasons have to do with local politics and local histories, and particularly, the differing nature of grievances and government connections in those two areas. This is not unique to Afghanistan; many insurgencies around the world stem from real grievances.

To recognize that a group had, at one point, legitimate grievances is not the same as saying the group acts legitimately to address those grievances. Armed groups often take a life of their own, and their ultimate purpose is usually to ensure their own survival and potential for obtaining power.

I describe in the book how the Taliban quickly came to mirror the actions of the very warlords they were fighting. They are a force of oppression, just as many of the other armed actors in the conflict.

Leave a Comment