Imperatives of pragmatism: A new era for German-Israeli ties during the 1980s–1990s

The Israeli-German relationship during the 1980s and 1990s was one of the most sensitive and dynamically evolving friendships in post-war international relations. Based on the trauma of the Holocaust, the German-Israeli relationship has changed over the years from moral responsibility to pragmatic cooperation, depending on internal political reasons but also changing international circumstances.

The early 1980s were a time of high tension, especially since the election of the Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin in 1977. Begin, a Holocaust survivor and unrepentant nationalist, distrusted Germany deeply. He argued fiercely with West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, and relations reached a nadir in 1981, when Germany announced that it would sell tanks to Saudi Arabia, against the wishes of Begin.

He publicly hit out at Schmidt, referring to his Wehrmacht past and accusing him of failing to “grasp” Jewish suffering. This confrontation exposed the fragility of the so-called “special relationship” and raised questions as to whether Germany would stay on the fence between its historical guilt and its growing geopolitical ambitions in the Arab world.

The Venice Declaration and the Europeanization of German policy

The 1980 Venice Declaration, supported by West Germany and the European Economic Community (EEC), heightened Israeli worries. It endorsed Palestinian self-determination and indirectly acknowledged the PLO, a change that Israel viewed as a betrayal. But for Germany, this was the “Europeanization” of its Mideast policy, an attempt to join forces with European partners while not appearing to exclusively side with Israel. This move towards multilateralism would develop to become a signature of German foreign policy.

The 1982 Lebanon War

Another pivotal intersection was the 1982 Lebanon War. When Israel laid siege to Beirut and massacred Palestinians in refugee camps, it created a moral discomfort in Germany. While the West German government didn't say anything publicly the conversation inside West Germany grew negative.

A generational change was at play: young Germans, unburdened by feelings of guilt over the Holocaust and eager to see Israel’s policies questioned through the prism of human rights. Such an internal debate pushed the boundaries of Germany’s traditional solidarity with Israel and showed an increasing willingness to move more independently in the matter of Middle East politics.

The Kohl era: Pragmatism and reconciliation

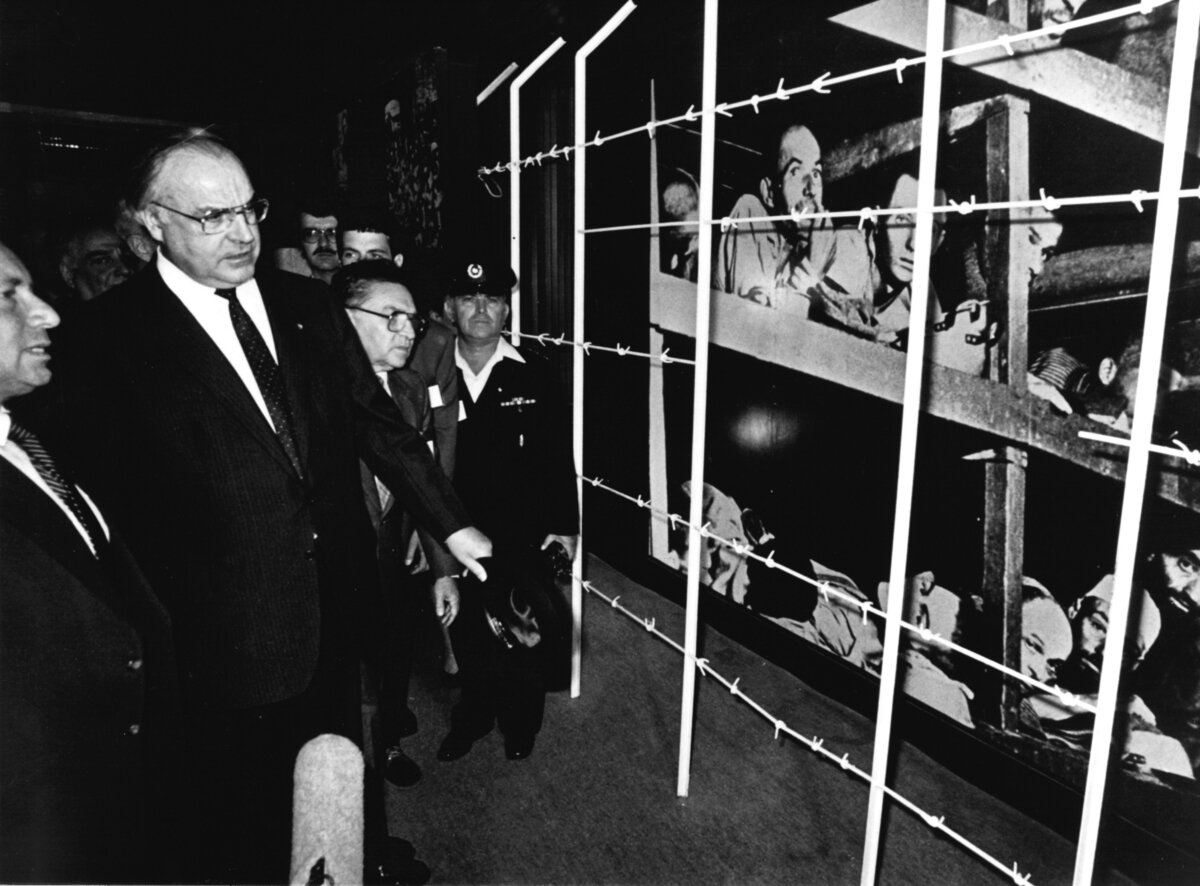

1982 saw a breakthrough in Helmut Kohl's chancellorship. Kohl wanted to mainstream German nationalism while ensuring its close links with Israel. In his address to the Knesset in 1984, which was titled the "mercy of late birth," he caused some furor for suggesting post-war Germans should not have to bear the full guilt for the Nazis.

Despite verbal blunders, Kohl’s administration did a great deal to strengthen German-Israeli relations in practice. Germany soon emerged as one of Israel’s closest European allies as the two countries expanded cooperation in trade, technology, and defense.

Yet, the relationship morphed. If it was once defined by guilt and moral responsibility, it had, by the decade of the 1990s, been animated more by interest and practical considerations. But both sides signaled that they understood their relationship needed to be recalibrated in light of changes in German policy, as Germany sought a new role and new weight in global affairs and Israel sought to contend with new structures in the region.

In summary, the 1980s and 1990s can be considered a time frame of German-Israeli relations’ change. What had started as a judgmental, frequently volatile affair had developed over time into mostly, if not always, measured collaboration. This transformation was a product not only of historical reckoning but also of the necessities of diplomacy in a world in flux.

The 1990s: Reunification, crisis, and strategic partnership

The 1990s have been a critical decade in the development of German-Israeli relations from a burdened past to a pragmatic and multi-dimensional partnership. It was characterized by German reunification, changes in the region, crises that strained trust and closer cooperation based on a joint dedication to memory and security.

The unification of Germany in 1990 provoked great anxieties in Israel and Jewish diaspora communities. For many, the division of East and West Germany after World War II had represented the consequences of Nazi atrocities, and reunification brought concerns of a resurgence of German nationalism. Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir publicly said he was worried that a united Germany would rekindle perilous ideologies.

A symbolic and deeply conciliatory gesture however came in April 1990, when East Germany’s new parliament formally assumed responsibility for Nazi crimes and apologized for its earlier anti-Israel policy. A visit by representatives of both German parliaments to Israel conveyed a new readiness to reckon with history and restore trust.

The reunification renewed for Germany the imperative of upholding its moral and political commitment to Israel. For Israel, it was a test of confidence in Germany’s democratic maturity and in its capacity to come to terms with the past and look to the future.

The Persian Gulf War and the “historical responsibility” doctrine

Tensions flared up again during the 1991 Persian Gulf War when it came to light that some German companies had supplied Iraq with chemicals and electronics that could be used in warfare.

This raised alarms in Israel about possible chemical attacks, especially given the painful memories of the Holocaust for survivors. To address the growing fear, German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher visited Jerusalem, and Germany later sent Israel two submarines.

This situation reinforced the idea of historische Verantwortung, or Germany’s responsibility toward Israel, becoming a key part of its foreign policy. It also showed the limits of that commitment, since business interests meant that sensitive tech could end up in the hands of Israel's enemies.

During the 1990s, Germany worked to strengthen its ties in the Middle East, often stepping in as a mediator between Israel and its neighbors. Although these efforts illustrated Germany’s goal of being a bridge-builder in the region, they did raise some concerns in Israel about Germany’s willingness to interact with hostile nations.

The Essen Declaration and Israel’s “special status” in Europe

A key moment came in December 1994 with the Essen Declaration when Chancellor Helmut Kohl managed to secure special status for Israel within the European Union. This allowed Israel better access to European markets and political opportunities. For Germany, it was a sign of its ongoing commitment to Israel's security and its role in Europe.

Generational change and civil society

Even with all the changes, there were still some tensions. The Holocaust is a key part of German-Israeli relations, and German leaders often stated that Israel’s safety is crucial for Germany. Still, this support wasn't always strong. Germany started to criticize Israel’s settlement policies more openly, which showed a shift towards international law and human rights in its foreign dealings.

Younger generations also changed how these two countries interacted. As memories of the Holocaust faded, many young Germans and Israelis looked for new ways to connect. Programs that focused on culture, education, and community work began to thrive. But this shift also caused some disagreements, as people began openly discussing memory, identity, and how far criticism should go.

The “Europeanization” of German policy

Another change in German-Israeli relations came from Germany becoming more involved in the EU. As it worked closely with the European Union, Germany often framed its Middle East views as part of a broader European approach. While this gave Germany an edge in diplomacy, it somewhat lessened how unique its relationship with Israel felt to Israelis.

By the late '90s, German-Israeli ties had changed a lot. What started as a relationship filled with guilt and pain turned into a practical partnership. Germany became Israel’s strongest ally in Europe, a key player in the EU, and a partner in both crises and peace efforts. The relationship still evolved, influenced by history, changing identities, and the shifting world landscape, balancing between memory and real-world politics.

Leave a Comment