From the flame to Michelangelo, and from Michelangelo to the mouth harp: The struggle for human art

TEHRAN – Before the accumulation of colonial wealth and the rise of institutional gatekeeping, art existed in forms that were raw, localized, and intimately bound to lived experience. It emerged through craft, ritual, oral expression, and communal aesthetics—untethered from formal complexity or market logic.

These early forms were not simplistic in meaning, only in structure; they communicated grief, celebration, cosmology, and survival in languages shaped by environment and necessity. There were no academies to certify, no galleries to curate. Artistic legitimacy came from shared participation and resonant expression, not technical mastery. This was art as presence, not performance—unfiltered, embodied, and collectively understood.

In that period, the economy of art unfolded in two distinct modes. One took shape within social life itself—teahouses, village gatherings, domestic spaces—where artworks were neither priced nor sold, but exchanged through mutual presence and shared necessity. The artist’s relation to the audience resembled a gift economy, not because of charity, but because fulfillment of human need replaced monetary value. There was no marketplace—only reciprocal recognition. In contrast, the second mode belonged to the court and the Church, where art was assigned monetary value, paid for, and possessed. It became a financial asset, embedded in systems of price, ownership, and display.

Colonial expansion facilitated the accumulation of wealth, giving rise to a merchant and capitalist class capable of commissioning art. These commissions did not reflect deep cultural insight, but served as visual affirmations of financial standing and social rank. Art entered bourgeois homes not through aesthetic intimacy, but through transactional display. Yet as market demand widened, so did the realization that creative potential was distributed far beyond elite circles—any individual with modest talent could produce cultural expression. The gap between expansive creative capacity and a demand that had grown but remained limited led to a structural problem: the system required mechanisms to regulate and restrict artistic supply.

As wealth accumulated and artistic production became more widespread, individuals and institutions began constructing aesthetic rules that claimed to define legitimate art. These rules—centered on technique, complexity, and pedigree—were not neutral guidelines but tools of exclusion. By presenting their standards as universal, they created a framework to sift and sort artists, validating a select few while marginalizing the rest. Academies and tastemakers formalized these codes, transforming them into criteria for economic access and cultural recognition. Through this system, aesthetic control became economic control: regulation of form justified regulation of market. Art was no longer open expression—it was filtered compliance.

As aesthetic hierarchies solidified, dominant centers like Athens—and their European continuation in Vienna—defined “depth” and “meaning” through their own cultural lens, presenting it as universal. This framework marginalized forms of artistic expression rooted in everyday life: domestic art, pastoral craft, teahouse aesthetics. These were excluded not for lack of substance, but for failing to mirror elite conceptions of refinement. The claim to depth became a tool of suppression; complexity, as defined by the center, rendered lived experience irrelevant. Through this fabricated standard, power dismissed what it could not possess, silencing art born outside its sanctioned domains. Art was now a concept fully absorbable into the logic of a money-centered economy.

As academic art consolidated its authority, iconic figures emerged to embody its sanctioned ideals: Beethoven in music, Goethe in literature, Ingres in painting, and Rodin in sculpture. These names became more than artists—they were symbols of mastery, depth, and cultural legitimacy.

Around them, artistic circles formed: salons, cafés, and gallery scenes where taste was curated and affiliation signaled status. These spaces fostered not only aesthetic exchange but economic consolidation. The producers of culture—writers, composers, painters—became a distinct class, aligned with wealth and institutional power. In Europe, then America, and beyond, art was no longer a vocation—it was a profession embedded in capital.

The label “naïve” was crafted not to describe, but to exclude—used by institutions to bar unsanctioned creators from entering the cultural economy. It allowed gatekeepers to dismiss rural, domestic, and unschooled art as lacking depth, shielding elite spaces from disruption. Yet academic control was not absolute. When demand briefly surged—through market spikes or collector trends—institutions responded not by expanding access, but by creating small, symbolic openings. Naïve art was permitted in marginal corners of galleries, not as recognition but as containment. These gestures absorbed surplus demand without threatening hierarchy, turning aesthetic tolerance into a calculated tool of economic regulation.

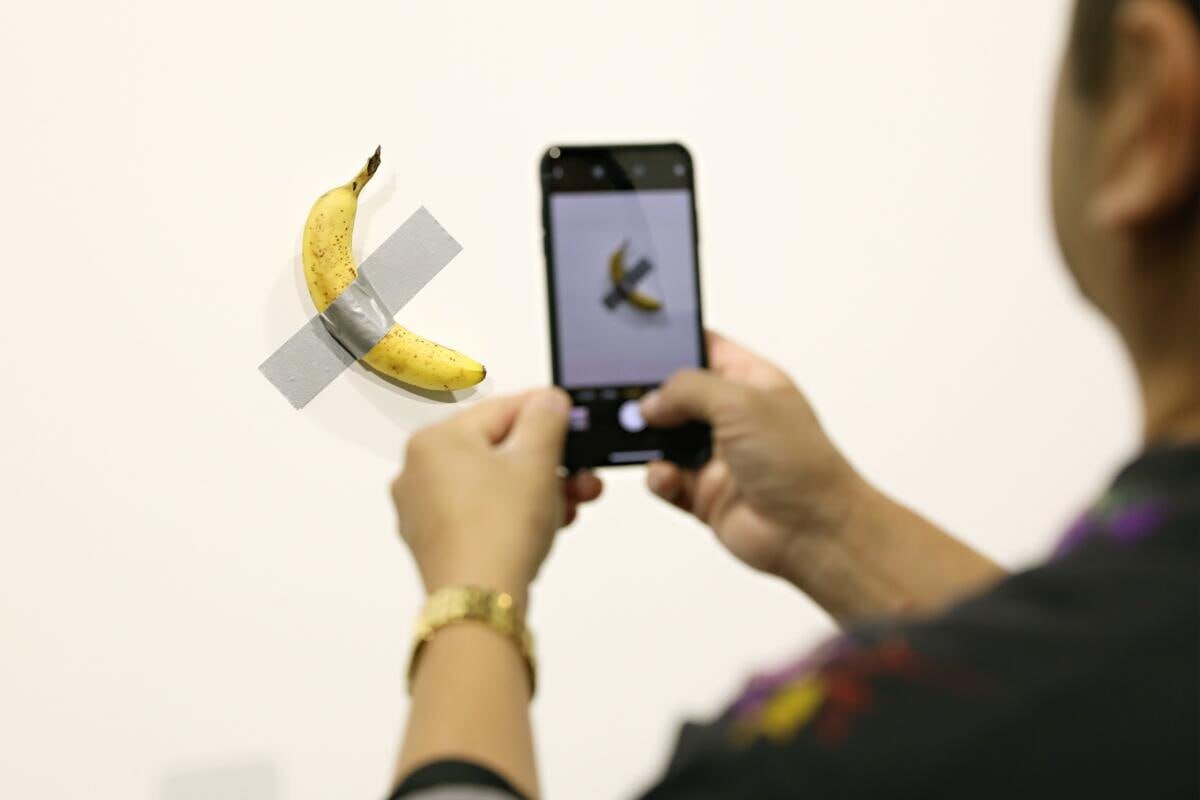

As the Athenian-Viennese model of cultural refinement became a tool for exclusion, its authority operated not through genuine depth but through rigid dismissal of human taste. This framework, though cloaked in intellectual prestige, was brutally indifferent to the lived preferences of emerging audiences. Wealthy American cowboys and their oil-rich cousins, newly empowered by capital, preferred country music over Bach or Beethoven—rejecting the dominance of meaning as the sole criterion of artistic value. Their tastes exposed the artificiality of elite standards. In response, the creator class, unwilling to relinquish its symbolic control, opened a strategic detour: the rise of anti-meaning movements. In literature, this included surrealism and absurdist theatre; in music, atonal composition and minimalist repetition; in visual arts, cubism and dadaism. These movements did not democratize art but reasserted control by declaring meaning irrelevant. Thus, exclusion persisted, now disguised as radical openness.

As internet access became universal, every individual turned into a broadcaster—no longer needing to flatter gatekeepers for a slot in curated media. Simultaneously, the rise of credit-based currencies and cryptocurrencies triggered an artificial surge in purchasing power. The art market, now fused with entertainment, expanded beyond recognition. Those who remained within the old framework retained academic authority, but surrendered the economic terrain to Instagram girls and viral personalities. The symbolic capital of art was preserved in theory, while its financial capital migrated to the domain of algorithmic visibility.

As sociological and anthropological analyses of artistic transformation proliferated, a conspicuous silence surrounded the economic dimension. The economy of art—its pricing, its commodification, its market logic—was treated as a contaminant, an indecent intrusion into the sanctified realm of aesthetic discourse. Like urine or feces, it was something to be expelled from polite analysis, too vulgar to name, too disruptive to include. This omission was not accidental; it was ideological. By refusing to confront the economic substrate of artistic change, these disciplines were forced to interpret developments through convoluted, often incoherent parameters. The result was a body of theory that strained to explain cultural shifts while ignoring the very forces that shaped them.

A more human future for art is not a utopia, it’s a rehearsal we can start today. In this future, we stop tagging prices to gestures, stop pretending that meaning and depth are gatekeepers to culture. The old excuses—Athenian prestige, Viennese finesse—have already crumbled. So, we quit chasing the sterile glamour of legal Instagram porn and turn back to the floor we started from. We sit in circles. Someone plays a mouth harp. Someone else sings out of tune. We clap, not perfectly.

Kids draw lopsided houses and giant dogs. We hang their drawings crooked on the wall. Next month we pull them down and hang new ones. And no one asks whether they smell like Kant, or Heidegger, or Plato, nor of Wall Street. They smell like breath after tea. Like fingernails with pigment under them. Like people trying, and trying again—like human beings, like the child of man. And with laughter and joy, we will kick over the tables of the money changers in the temple.

Leave a Comment