Islamophobia, orientalism, and power: The Iranian case

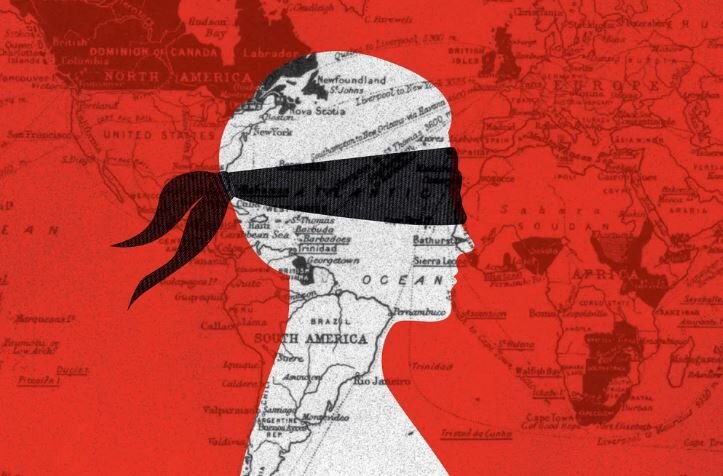

MADRID – In recent days, the coordinated attack by the United States and Israel on Iranian nuclear facilities—under the supervision of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)—has once again brought to the forefront a discursive framework deeply rooted in the colonial tradition: the portrayal of Iran as an irrational, unpredictable, and therefore dangerously uncontrollable actor.

Far from being a novel narrative, it draws on an orientalist genealogy that, since the 19th century, has constructed West Asia and Islam as the irrational “Other,” incapable of self-governance and in need of external tutelage.

The Iranian case is paradigmatic. Although its nuclear program remains under international supervision and shows no signs of diversion toward military ends, official rhetoric continues to stress the need to “contain” a country that—according to this narrative—cannot be trusted due to its supposed theocratic “essence.” This logic not only preemptively justifies aggression but also strips Iran of its sovereignty, history, and agency, reducing its political complexity to a dangerous caricature.

A critical reading, however, allows us to deconstruct these stereotypes. Far from being a dogmatic system closed in on itself, Islam has cultivated over the centuries a rich and plural tradition of critical thought, aimed both at its own canon and at the social and political structures surrounding it. This critical practice is not the exclusive domain of intellectual elites; it is expressed in everyday life—in mosques, markets, homes, and public spaces. Muslims not only practice their faith, but interrogate it, debate it, and reformulate it within discursive frameworks that, rather than diluting doctrinal coherence, reinforce its ability to project into the future.

This approach makes it possible to dismantle one of the pillars of the orientalist imaginary: the representation of the Muslim—and by extension, of societies like Iran’s—as inherently irrational, trapped in “religious” passions and incapable of strategic logic. Through this lens, Iran is turned into the emblem of radical otherness, a kind of “absolute other” embodying the West’s most persistent “fears”: fanaticism, sacralized violence, and irrationality. This construction depoliticizes its international actions, empties its strategic decisions of meaning, and turns it into a legitimate object of intervention.

Reducing Iran to the paradigm of irrational political Islam reinforces a colonial matrix that denies the legitimacy of alternative forms of rationality. The aim is not to ignore the tensions, but to acknowledge that its political project responds to a historical, cultural, and geopolitical logic that must be understood on its own terms. To deny this is not only to reinforce Islamophobia but also to obstruct any serious understanding of political movements from the Global South that challenge the Western monopoly on the definitions of rationality and politics.

Islamophobia as a structure of power

Islamophobia should not be understood merely as a cultural prejudice or religious phobia, but as a specific form of structural racism directed at expressions of the Muslim identity, or at any public manifestation perceived as such. This discriminatory logic is reproduced across media, institutions, and international diplomacy. In the case of Iran, it manifests as a systematic hostility that does not necessarily respond to the country’s actions, but rather to its cultural and religious identity.

This form of symbolic violence—known as epistemic violence—operates by denying people the right to define their own ethical, political, and civilizational frameworks. By delegitimizing their own rationalities, global asymmetries are reinforced, and an international architecture is justified that is designed to exclude, isolate, and punish those who fall outside the liberal Western canon.

Overcoming this approach requires a critical revision of the language we use to describe Islam and actors like Iran. It is not about idealization, but about restoring the historical and political depth of these projects. Ultimately, dismantling Islamophobia—in all its forms—demands the construction of a new political vocabulary, one that does not associate difference with threat, nor religious discourse with irrationality.

The attack on Iran and the breakdown of the international order

The bombing of Iranian nuclear facilities is not merely a unilateral act of aggression; it is a warning sign of the erosion of international law. The nuclear non-proliferation regime, supposedly designed to ensure global security, is applied with a double standard: while Western powers retain their atomic arsenals without serious disarmament commitments, countries from the Global South face sanctions, surveillance, and military threats—even when they comply with international norms.

The rhetoric that legitimizes these interventions draws on a tired yet still effective narrative: the confrontation between civilization and barbarism. This binary logic, which historically justified colonial wars, still serves today as a moral pretext. As decolonial thought has pointed out, this discourse is not only unjust—it is profoundly destabilizing: by denying the agency and rationality of others, it perpetuates cycles of violence and reproduces an international order based on exclusion and hierarchy.

In this context, Iran is not only a victim of Islamophobia—it is also an uncomfortable mirror reflecting the failure of the universal principles the West claims to uphold. Reclaiming the possibility of a more just international politics requires not only putting an end to military violence but also dismantling the symbolic frameworks that make such violence possible. Only then can a truly plural order emerge—one in which difference is not punished, but heard.

Leave a Comment