A look at Israel’s strategy to Balkanize Iran and why it will fail

MADRID - In West Asia’s geopolitical landscape, security rarely boils down to a purely defensive matter; above all, it is a narrative of power. Israel, shaped by a history of regional isolation and an identity forged in exceptionalism, has turned security into the lens through which it interprets every opportunity and threat. But what happens when security becomes an obsession and the central justification for all foreign policy?

Israeli doctrine has made alliances with ethnic and religious minorities a strategic tool to influence and ultimately fragment its adversaries. Iran, with its complex multiethnic composition, presents itself as a tempting target for this "divide and conquer" policy. Promoting separatist narratives or covertly supporting peripheral groups is not merely a tactical move, but part of a broader vision: to weaken the internal cohesion of a regional rival and reshape the balance of power in the region.

However, this security-driven approach is neither innocent nor neutral. By reducing entire communities to mere pieces in a geopolitical game, it strips these actors of their agency and legitimizes intervention under the pretext of protection. Security, in this framework, ceases to be a universal right and becomes a technology of control that justifies surveillance, manipulation, and social fragmentation. It is a model that, as various critical voices have pointed out, turns difference into threat and diversity into a battlefield.

But there is more. Analysts such as Sahar Ghumkhor urge us to look beyond the surface: when the logic of security is imposed, the histories of exclusion, resistance, and negotiation within affected communities become invisible. The instrumentalization of minorities does not reflect a genuine concern for their rights but their situational utility within external power agendas. Thus, legitimate demands for justice and recognition are subordinated to strategies with little to do with self-determination.

Within this context, Israeli policy toward Iran reveals the limits and dangers of a securitized vision taken to extremes. It not only perpetuates regional instability but also reinforces colonial hierarchies and reproduces a logic of exception that justifies nearly any action under the banner of security.

This article aims to explain Israel’s political desire to balkanize Iran and how this policy overlooks the resistance of different ethnic groups within the Islamic Republic against these attempts to foment internal divisions.

The role of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies

One of the most active actors in this balkanization strategy is the neoconservative Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), based in Washington. Brenda Shaffer of the FDD has argued that Iran’s multiethnic composition constitutes a vulnerability that can be exploited. Her stance aligns with a recent editorial in the Jerusalem Post, which, following the initial Israeli attacks in the recent war against Iran, openly called on former President Trump to support the country’s dismemberment.

The editorial proposed forming a “Middle East coalition for the partition of Iran” and granting “security guarantees to Sunni, Kurdish, and Baloch regions willing to separate.” The Jerusalem Post has explicitly advocated that Israel and the United States back the secession of what they call “South Azerbaijan,” referring to the northwestern Iranian provinces predominantly inhabited by Azeri populations.

These ideas are not isolated statements; they reflect a strategic approach to dismantle Iran’s political unity by using ethnic diversity as leverage to generate instability.

Where balkanization comes from

From a theoretical standpoint, the end of the 20th century marked the rise of ethnonationalism in international politics. The dissolution of the Soviet Union and the fragmentation of Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia highlighted the central role of ethnic conflicts in global politics, attracting the attention of scholars and strategists alike.

The dispersion of ethno-religious groups across various states and their transformation into active fault lines threatened the territorial integrity and social cohesion of states with ethnic diversity. Consequently, identity claims were seen not only as challenges but also as opportunities for certain countries’ foreign policies.

As a result, many powers began supporting groups beyond their borders to gain influence and power, exploiting others’ internal tensions to strengthen their regional position.

When Israel began to look to balkanization

Every security doctrine arises from a combination of historical, structural, and subjective factors. In Israel’s case, the so-called Periphery Doctrine — the strategy of forming alliances with non-Arab or peripheral actors in the region to counter its isolation — stems from an existential reading of threat and a political identity based on exceptionalism and suspicion.

This doctrine was formulated by David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, after the Suez Crisis of 1956 as a way to break the Arab blockade by seeking support from non-Arab regional countries (such as Turkey and pre-revolutionary Iran) and ethnic minorities on the periphery facing Arab pressure.

The colonial and exclusionary nature of the Zionist project, along with regional isolation, fostered a security mindset that perceives all differences as a threat and any neighbor as a potential enemy.

Beyond states, Israel has fostered covert ties with ethnic and religious minorities in Arab and Islamic countries to destabilize them. Support for minorities — from Kurds to Druze — is a key element to fragment the Arab bloc and maintain strategic superiority.

Israeli theorists have openly expressed this policy. Aryeh Ornstein proposed dissolving Arab countries into tribal entities as an opportunity for Israel, while Jabotinsky advocated aiding Kurds to weaken Arab states. These ideas reflect a deliberate project to foment sectarianism and divide neighboring states.

After the 1967 war and Israel’s military rise, this strategy was reinforced and formalized as part of the regional domination project.

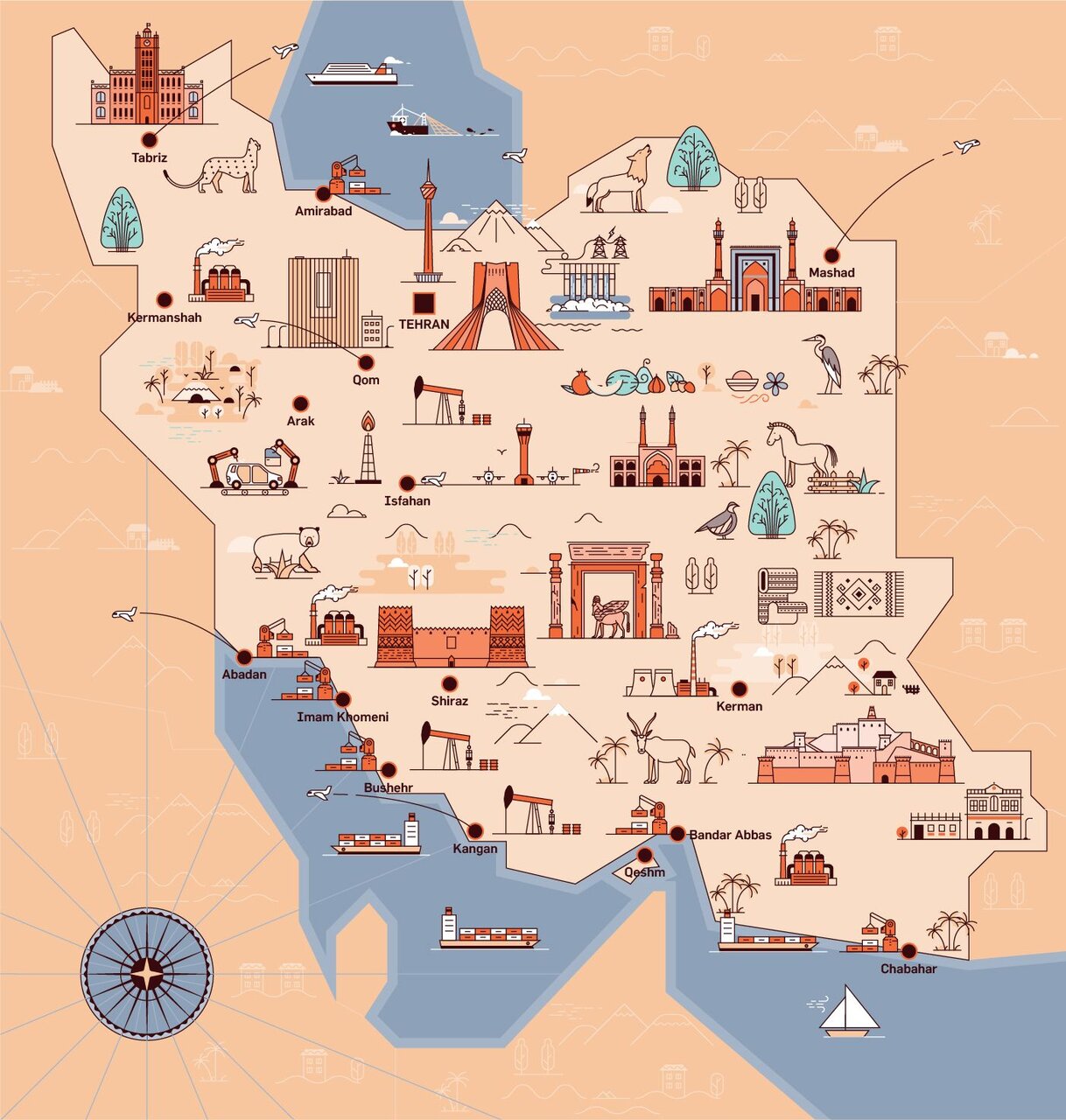

The Iranian reality

Israel and its Western patrons often overlook a key distinction: Iran's historical continuity sets it apart from many other nations in West Asia. While some historians have characterized other regional countries as "artificial" due to their relatively recent formation, Iran boasts a history spanning millennia, claiming status as the world's oldest continuously existing nation.

The Soviet Union, for instance, comprised diverse nations and territories previously under different sovereignties. In contrast, Iran has maintained a continuous national identity for millennia, with a population that has identified as Iranian throughout its history. Iran is a country of marked ethnic and linguistic diversity, but this diversity exists within a framework of political and territorial cohesion that has always existed, and is currently being maintained by the Islamic Republic.

From a geographical perspective, Iran is divided into a more homogeneous central part and heterogeneous peripheral units. Yet throughout its history, these parts have shown complementary and coordinated behavior within the state, ensuring robust political, territorial, and national continuity.

An example of this continuity was Iraq’s invasion of the Khuzestan region in 1980 during the Iran-Iraq war. The Iraqi offensive was accompanied by the slogan of Arab national unity and divisive propaganda based on ethnic differences. Although the western part of Khuzestan is predominantly Arab, the invasion met significant local and regional resistance.

Iran is neither a fragile state nor an ethnic mosaic on the brink of collapse. It is a nation of approximately 90 million inhabitants with a deep historical and cultural identity that transcends its diverse components. Those promoting balkanization often fixate obsessively on ethnic plurality — Azeris, Kurds, Balochs, Arabs — recurrently underestimating the integrative strength exerted by the Islamic Republic.

The most paradigmatic case of this fallacy is Iran’s Azeri population, the second largest after the Persians. Azeris predominantly inhabit the northwest—in provinces such as West and East Azerbaijan, Ardabil, Zanjan, and Qazvin—and also extend into Hamadan and western Gilan. Moreover, a significant Azeri community is fully integrated into key urban centers like Tehran, Qom, and Arak. It is important to note that Azeris hold prominent social and political positions in Iran, with intellectual, religious, scientific, and cultural elites playing significant roles locally and nationally.

In this regard, key figures within the Iranian system, such as the current president, Masoud Pezeshkian, and Leader of the Islamic Revolution, Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Khamenei, belong to this minority.

Furthermore, studies like those by Rasmus Elling and Kevan Harris, based on an extensive social survey conducted in 2016, show that many Iranians do not identify exclusively with a single ethnic group but acknowledge belonging to multiple identities.

Therefore, the hypothesis shared by Israel and think tanks such as the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD)—that under external pressure, like the recent escalation between Iran and Israel, minorities would rise against the central government—has proven incorrect. The effect observed after the Israeli attack was precisely the opposite: a strengthening of national unity and social cohesion within Iran.

The reality is that Iranian national cohesion far surpasses any external attempt at fragmentation or destabilization. Under the firm and sovereign leadership of the Islamic Republic, Iran has consolidated a strong identity that integrates its diverse communities into a shared project of resistance and self-determination. This unity not only reflects the country’s historical and cultural strength but also its capacity to face and neutralize threats aimed at undermining its territorial and political integrity.

In the wake of the recent Iran-Israel war, some of the most intense expressions of mourning and patriotism in Iran in recent years have been witnessed. Massive gatherings of mourning have been marked by elegies and verses filled with references to Iran, drawn from classical Persian literature as well as contemporary popular songs, nationalist poetry, and patriotic hymns. These cultural and social acts reflect a profound sense of collective identity that emerges strongly in response to any external aggression, demonstrating the solidity and resilience of the Iranian national project. Thus, far from fragmenting society, attempts at balkanization have served to reinforce internal cohesion and Iran’s capacity to resist as a nation-state.

Leave a Comment