Iran and the power of the drone

How technological sovereignty became the core of the country’s national strategy

MADRID - In the global landscape of the 21st century, technology has become one of the main sources of power and autonomy. It is no longer enough to have a strong army or access to natural resources: real independence depends on a country’s ability to develop its own technological solutions and sustain its strategy without relying on others. In that sense, Iran has made drones a pillar of its sovereignty a tool that blends innovation, resilience, and political ambition.

More than mere military devices, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) symbolize a response to decades of sanctions and external pressure. In the face of isolation, Tehran bet on self-reliance and managed to turn necessity into strategic advantage. Its drone program spanning surveillance, reconnaissance, and precision operations reflects not only technical progress but also a reaffirmation of independence in an international system that is fragmenting and reshaping itself.

In a world where great powers strive to preserve their influence, Iran has found in technology its own language of power. Its drones are more than weapons: they represent a country’s determination to preserve its decision-making autonomy and defend its interests without bending to others’ rules. They are, ultimately, a declaration of sovereignty in an era of global uncertainty.

According to reference documents such as the U.S. Unmanned Systems Integrated Roadmap, unmanned systems have become the fastest-growing segment of the global aerospace industry. This is not a mere technical evolution but a paradigm shift that redefines the very nature of air power. Industry estimates suggest that the share of drones in advanced air forces has grown from virtually zero in the 1980s to around 23% today, while manned aircraft continue to decline.

Against most Western expectations, Iran has not only understood this transformation but embraced it as a cornerstone of its defense strategy. Where others see a supporting instrument, Tehran sees a vector of technological autonomy and regional projection, integrating drones into a doctrine that combines deterrence, self-sufficiency, and adaptation to the shifting balance of global power.

Sanctions as a driver of innovation

For years, the dominant narrative in Washington and other Western capitals portrayed Iran as an isolated and technologically backward state, doomed to military obsolescence under the weight of international sanctions. But that reading overlooks a key reality: sustained pressure not only punishes it shapes. In Iran’s case, sanctions did not destroy its technological capacity; they transformed it into a force for invention and autonomy.

Deprived of access to global defense markets, the Islamic Republic’s security establishment was forced to look inward. More than a political choice, it became a matter of strategic survival. National plans such as the Comprehensive Aerospace Development Program and the Sixth Five-Year Development Plan formalized that orientation, turning technological self-sufficiency into a guiding principle. From that pressure emerged a domestic drone industry adaptable, efficient, and capable of producing functional, affordable systems that combine simplicity, low cost, and operational effectiveness.

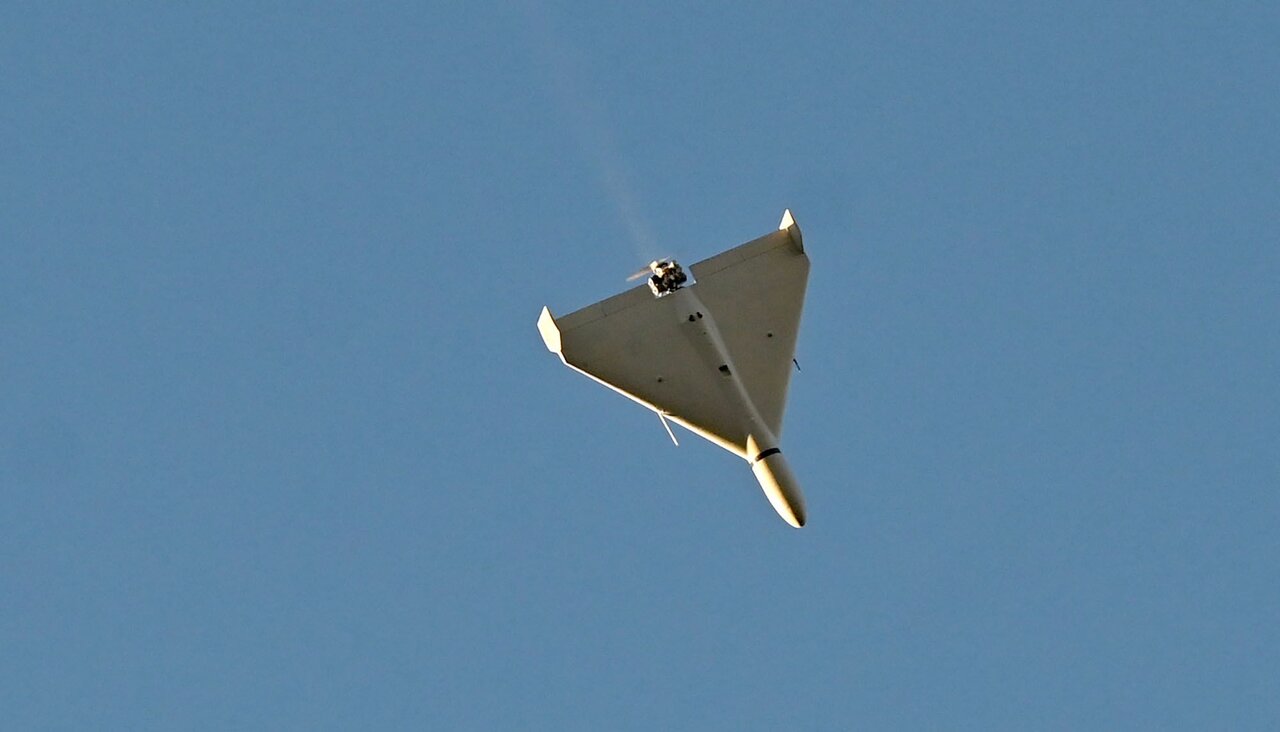

The drone thus became an answer to Iran’s structural defense dilemmas. It allows for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance at low cost; the projection of force without human casualties; and domestic production shielded from external constraints. The Shahed family led by the now famous Shahed-136 embodies this philosophy: sufficient technology, mass production, and industrial resilience. In a world of global asymmetries, Iran has managed to turn scarcity into strategy and sanctions into incentives for innovation.

The role of Iranian drones cannot be understood without looking at the geopolitical chessboard on which Tehran’s strategy unfolds. Surrounded by U.S. military bases and facing regional rivals with privileged access to Western technology such as Saudi Arabia and Israel Iran has articulated a doctrine of deterrence by denial, rooted in asymmetric warfare. Within this framework, UAVs have become the most versatile and effective instrument of its defensive posture.

These systems enable Iran to exercise what some theorists call denial power : the ability to prevent a more powerful adversary from fully controlling a space or to impose prohibitive costs for attempting to do so. Low-cost drones or those transferred to allied actors such as Hezbollah in Lebanon or the Ansarullah in Yemen can threaten critical infrastructure, commercial vessels, or energy facilities, thereby altering the strategic calculus of regional and global powers. A loitering munition costing a few thousand dollars can damage a warship worth billions or disrupt oil supplies, shifting the balance of power at minimal expense.

The impact of Iranian drones, alongside the country’s missile program, extends far beyond the military domain. Their development and deployment have strengthened Tehran’s diplomatic position by giving it additional leverage in dealing with the West. The spread of these systems serves as a constant reminder to Washington or Tel Aviv that a direct confrontation with Iran would come with unpredictable costs.

The Shahed and the paradigm shift

The fact that drones are here to stay in modern warfare is now taken for granted. But their importance is not merely technical: they have also expanded access to air power once reserved for nations with enormous defense budgets.

The Shahed-136 illustrates that logic. Its design deliberately avoids the complexity and cost of radar-evading aircraft such as the U.S. RQ-170 Sentinel (which Iran claims to have captured and reverse-engineered), opting instead for a philosophy of sufficiency: a low-cost engine, GPS-based navigation (with its known vulnerabilities), and a significant payload. In practice, it functions as a cheap, reusable cruise missile designed for serial production.

This simplicity is its main operational virtue: it enables mass manufacturing, ease of maintenance, and deployment by actors with limited resources, while overwhelming air defenses built to intercept a small number of high-value targets. Against such systems, a swarm of dozens or hundreds of Shaheds presents both a tactical and economic dilemma: neutralizing each one with advanced surface-to-air missiles can cost many times more than the drone itself, leading to sustained financial and logistical strain for the defender.

The strategic effect is clear. This approach forces a reassessment of doctrines still anchored in qualitative technological superiority: innovation does not always mean developing the most advanced system, but designing one that pragmatically exploits the adversary’s economic and operational vulnerabilities. In that sense, necessity being frugal under sanctions and restrictions has become an operational strength and a modern lesson in applied asymmetry.

The reaction of the United States and its allies to this challenge has so far been largely reactive and military in nature. Efforts have focused on developing more effective counter-drone systems and tightening sanctions to constrain Iran’s supply chains. While such measures may make tactical sense, they fail to address the root of the issue: Iran’s drone program is not the cause but the consequence of a long-standing policy of pressure that has deepened its pursuit of strategic autonomy.

Western soft power the ability to influence through cultural attraction and values has limited reach against a state that defines its identity in opposition to that very influence. In Iran’s case, resistance to Western hegemony is part of its founding narrative. Sanctions, far from eroding that narrative, have reinforced it, providing justification for national mobilization around technological self-sufficiency and sovereignty. The maximum pressure strategy has thus proved counterproductive, accelerating the very capabilities it sought to prevent.

The real challenge for the West is not merely how to shoot down Shahed drones, but how to manage the rise of an actor that has learned to turn adversity into influence. This requires a strategic reassessment that goes beyond the military dimension and considers the political, technological, and diplomatic implications. Through persistence and technological development, Iran has established itself as an unavoidable player in shaping the new regional security order.

Iran’s drone program ultimately embodies its determined pursuit of technological sovereignty. In an international context where technology is both a source of power and a means of exclusion, the ability to independently develop strategic systems has become a key component of national security. For Tehran, this is not a luxury it is a condition for political and strategic survival.

Far from the caricature of an isolated state resorting to improvised solutions, Iran’s trajectory in UAV development reflects a deliberate, coherent policy embedded in long-term planning. Sanctions and isolation did not halt that process; they shaped it. Rather than competing in the realm of cutting-edge sophistication, Iran has prioritized resilience, efficiency, and the smart use of asymmetry as the foundation of its defense doctrine.

The rise of its drone industry is not only a military achievement but also a political narrative of adaptation and autonomy in an increasingly fragmented world. It marks the end of the Western monopoly over advanced defense technology and signals a more plural and complex landscape, where middle powers armed with disruptive, low-cost systems can challenge larger ones and reshape regional dynamics.

To ignore this phenomenon or to dismiss it merely as provocation would be a strategic mistake. The future of warfare is fought partly from the air and at a distance, but its implications are profoundly political: it is about who controls technology, and with it, the ability to decide one’s own fate. On that front, Iran has shown a capacity for adaptation that forces the world to reconsider the very foundations of power in the 21st century.

Leave a Comment