Clues about Homo erectus, extinct species of archaic humans, discovered in western Iran

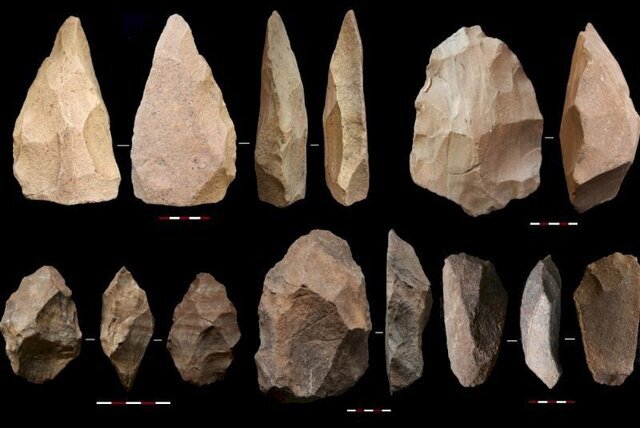

TEHRAN – A team of Iranian archaeologists has discovered stone tools such as ax and machete believed to be created by Homo erectus, an extinct species of archaic human, in the outskirts of Kermanshah in western Iran.

"The creators of those tools may have been the so-called 'Homo erectus' although other groups [of early humans] made similar tools, given the similar sites in other parts of Asia. It is highly possible that Homo erectus made these tools," ISNA quoted senior archaeologist Saman Heydari-Guran as saying on Wednesday.

Heydari-Guran who led the recent survey noted: "During a week-long survey in this area, tens of stone axes, utensils, and mother stones related to the [Lower] Paleolithic period were discovered, which according to their technical characteristics and typology are related to the Acheulean era.

Acheulean, from the French acheuléen after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand-axes" associated with Homo erectus and derived species such as Homo heidelbergensis.

"This is the first time in 60 years that tools from the Paleolithic period have been discovered in Kermanshah," the archaeologist said.

"In the 1960s, an archaeological mission from the University of Chicago, headed by Robert Braidwood, discovered a stone ax near Gakiyeh village and since then there has been no report of the discovery of such tools in Kermanshah."

Such axes are stone tools related to the [Lower] Paleolithic period and that were made 250,000 years to 1.5 million years ago, he added.

Elsewhere in his remarks, Heydari-Guran noted the recently discovered stone tools may date back to about 700,000 to one million years ago.

"Since there is currently no absolute historiography for this human settlement, it is not possible to give an exact date for the construction of these tools, but it is possible to predict a date of about 700,000 to one million years ago."

Braidwood discovered Tappeh Asiab, which is an Early Neolithic site situated on the outskirts of Kermanshah, in the central Zagros Mountains. The site was found during Braidwood's ‘Iranian Prehistory’ Project and was briefly excavated early in 1960. Asiab was one of the first Early Neolithic sites excavated in the central Zagros, and although the excavations at the site were never comprehensively published, it has played an important role in shaping our understanding of the Early Neolithic in this region. The area has been described as the deposits at Asiab as “a chaotic jumble of animal bones, freshwater clam shells, coprolites, flint working, and other artefactual debris, rocks and traces of fire and ash, as well as numerous debris-filled pits”.

The energetic archaeologist, Heydari-Guran, the remains of three Neanderthals have been discovered in Iran so far. “In previous [archaeological] seasons at Bawa Yawan, in addition to the discovery of a 42,000-year-old Neanderthal tooth, archaeological layers embracing cultural data from Paleolithic, Middle Neolithic, and post-Paleolithic periods were identified.”

The tooth, which is a lower left deciduous canine belonging to a six years old child, was found at a depth of 2.5 m from the shelter surface in association with animal bones and stone tools near Kermanshah. Stone tools discovered close to the tooth belong to the Middle Paleolithic period and a series of C14 dating suggests the Neanderthal is between 41,000-43,000 years of age which is close to the end of the Middle Paleolithic period when Neanderthal disappeared in the Zagros. Neanderthals were roaming over the Iranian Zagros Mountain sometimes between 40 to 70 thousand years ago.

A previous study performed by Heydari-Guran based in the Neanderthal Museum in Mettmann, and his international fellows such as Stefano Benazzi, who is a physical anthropologist at the University of Bologna, the analysis showed the tooth has Neanderthal affinities. Conducted by a team of archaeologists and paleoanthropologists from Iran, Germany, Italy, and Britain, the results of the study appeared on the online journal PLOS ONE in August.

Until the late 20th century, Neanderthals were regarded as genetically, morphologically, and behaviorally distinct from living humans. However, more recent discoveries about this well-preserved fossil Eurasian population have revealed an overlap between living and archaic humans.

AFM

Leave a Comment